A Small Mystery At Starvation Hill

Feb,2009 By Rene Rogers

I was just over 2-years old in 1929 when my family

moved from Louisiana to Gainesville, Florida.

We lived there for a while with my grandfather, George Foster, at

his place at the top of the hill on Kincaid Road a mile or so South of the

Hawthorne Road. He referred

to the area as The Starvation Hills.

As I later came to understand some of the geology of the area it

had once been a sand dune beach as Florida was being pushed up out of the

ocean due to “Plate Tectonics”.

Another feature of this geology was the sinkhole and as a 3-year

old I recall going to the bottom of one with my older brother near my

grandfather’s place. I

remember that we drank cold sweet water from a spring at the bottom.

I also recall that he found, over time, some small petrified

shark’s teeth and a few pieces of quartz in the gravel beds down there.

The importance of this sinkhole with regard to my

mystery here is that it was also a place where blocks of chert and perhaps

other stones could be harvested. Chert,

like flint, agate, jasper, and obsidian, etc., is useful for making flaked

stone tools. In particular,

chert is a natural glass that forms a razor-sharp edge when broken by a

sharp blow from another stone, or cobble.

This property is of primary importance in the making of stone tools

like arrowheads and knives, etc.

As I understand the geology, chert is formed as

nodules weighing some 20-pounds, much more or much less, in limestone beds

over many eons on the bottom of warm shallow seas.

The limestone is primarily the remains of shellfish like clams and

muscles and oysters, etc. After

the limestone formations have been lifted up off the ocean floor and

forests have developed around about, the rainfall on the dead leaves is

slightly acidic and the runoff in the form of underground streams slowly

dissolves the limestone. In

time the ground above collapses and a sinkhole is formed.

Somewhere along the way I was told that Alachua County, where I

grew up, was named after the Seminole word for “sinkhole”.

In any case there are numerous sinkholes in the area familiar to

curious guys like me. Most

notable is The Devil’s Millhopper, now a park West of Gainesville.

Warren’s Cave nearby is of similar origin, but it has not fallen

in yet.

The Kincaid Road is now paved, but during my college

days (1946-50) it was still a dirt road.

Some 2-miles past my grandfather’s old place it makes a sharp

right turn for 2+/- miles and there joins the road past Bouleware Springs

at Robinson Heights. Following

this road to the North takes us back to Gainesville past the Evergreen

Cemetery (where my grandfather and my father are buried).

The site of this housing development was a large vacant field in

those days where the occasional arrowhead could be found. Jackson’s Farm was across the railroad (now a bike trail to

Hawthorne) on the edge of Payne’s Prairie.

Jackson’s Farm, in contrast, is a prime hunting ground for stone

tools.

Bouleware Springs was the main source of the

Gainesville water supply when I was growing up, but it is now a public

park. The runoff is a creek

that flows to Payne’s Prairie along the North boundary of Jackson’s

Farm, that is no longer used for farming.

When I was in high school, my buddies and I used to camp beside the

creek and hunt for arrowheads on the farm.

We were almost never disappointed… particularly after plowing or

a heavy rain. We also noticed

an abundance of chert debris there but I don’t recall that we ever saw

this as the logical consequences of tool making on a larger scale.

At least I did not until much later.

Now I suspect that Jackson’s Farm was primarily an arrowhead

factory and that the tools were made for trading and commercial purposes

as opposed to hunting and fishing by those making the tools.

I was collecting arrowheads as a more-or-less serious

hobby in the late 1930s and I continued this hobby when I came back from

military service in 1946 and became a student at the University of

Florida. It was probably

during my junior year that I was riding my motor scooter past my

grandfather’s old place on Kincaid Road when I thought I saw an

arrowhead at the far edge of the road grading.

The Kincaid Road was not paved at this time and the county road

grader had passed that way a week or two earlier and a heavy rain had

fallen since. I stopped to

investigate and picked up the arrowhead before I noticed another speck of

exposed rock nearby and gathered up another one about the same size and

style. It was somewhat

unusual to find two arrowheads so close together on the surface, but

nothing to write home about.

A few weeks later, and after a heavy rainfall, I

passed the spot again and stopped to have another look.

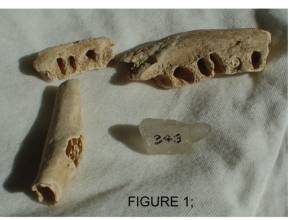

This time I was quite surprised to find a piece of a human jaw

bone… almost the same color as the sand, and with the texture of chalk.

It was obviously quite old.

Scraping around with my bare hands in the dirt a bit

produced another piece of bone also shown in Figure 1, but nothing further

at this time. Over the next

year or so I gathered a total of 12 arrowheads from the site and a small

piece of quartz, also seen in Figure 1.

It was quite some time before I recognized the quartz as an

“artifact” along with the bones and the arrowheads.

A close examination of the quartz, however, clearly shows a groove

around the small end that seems most likely designed for wearing the piece

as a pendant or personal decoration of some kind, perhaps in the ear or

nose or lip. Since quartz is

a moderately hard mineral it strikes me that forming this groove during

the Stone Age was not a trivial task.

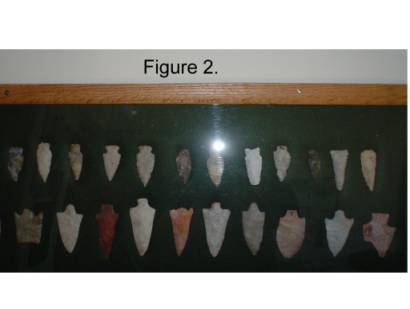

The arrowheads associated with this site are (mostly)

those shown on the top row of this display below.

(I say mostly because I am not absolutely sure that these are all

the precise dozen. More about

this later.)

A bit of history at this point seems in order so that

you may better understand why I describe this find as a “small

mystery” and the basis of some speculations I have.

A more complete account may be found at my page on the website of

the Southwest Museum of Engineering and Computing: http://www.smecc.org/r__m__r__new_article_on_aging.htm

As I explain in that article having to do mostly with

measuring the age of flaked stone tools from first principles. I found my

first arrowhead when I was around 5-years old.

By age 8-years I had a small box with maybe a dozen arrowheads

along with some fossils and petrified sharks teeth.

A neighbor took me to the museum associated with the University

where I learned that arrowheads were of near-zero interest to the

archaeologists there while pottery shards, of which I had none, were of

considerable interest to them. Those

artifacts held far more clues with regard to the lives of the primitive

peoples who had lived hereabouts.

Soon after this experience I learned from another

mentor, who was a flying instructor at the airport near my home, that he

knew of no worthwhile person who had the slightest interest in rocks.

I traded all of my arrowheads and fossils to some other kids on the

school grounds and concentrated on the more important matters having to do

with flying. My interest was

considerably revived when I found another arrowhead in the near vicinity

of what is now the terminal building at the Gainesville Municipal

Airport… as I explain in some detail in my website article.

When I was 13 years old I made friends with Snubby

B., a boy my age whose mother was my older sister’s landlady in

Gainesville. He was active in

the Boy Scouts and eventually persuaded me to join his troupe.

I soon learned that earning merit badges was a prime concern there

and that collecting things was one way to do that.

Stamps, coins, seeds, leaves, book matches, bottle caps, almost

anything was collectable as a path to advancement up the ranks.

My first campout with the troupe was at the site of

an “Indian Ceremonial Mound” near Bouleware Springs. This mound was perhaps 10-15 feet tall and around 30-feet in

diameter at the base and reasonably symmetrical. I soon learned that the scouts were permitted to dig into it

looking for artifacts, but the word was that nothing collectible had ever

been found there. Even so,

the scouts could dig if they were so inclined, but they were told to fill

any holes they dug with the dirt removed and to preserve the shape and

appearance of the mound. When

I visited the Bouleware Springs Park around 2003 I looked for the mound

and reckoned that it was located outside of the Northern boundary fence in

a region that was heavily overgrown with brush.

I asked a couple of people who seemed to have some official

position with the park and they had never heard of this mound.

Another member of Snubby’s troupe was Billy H.

He had some arrowheads that he had found at both his

grandfather’s place and at a dairy on the South edge of Payne’s

Prairie that was owned by his aunt. Snubby

also had several arrowheads, but his primary interest was collecting

stamps. Billy’s grandfather

was an avid stamp collector and the 3-of-us visited him several times to

hear stories as to how he had managed to accumulate such a notable

collection. We all got

several arrowheads each from him, but I can’t recall the circumstances.

I think perhaps that he gave them to us.

In any case I recall that he had a multi-colored arrowhead that he

referred to as his “calico” and that he intended to keep that one.

But the rest were of little or no value to him, except that he

would always pick one up if he came across it in his field.

For a while, Billy, Snubby, and I concentrated on

collecting stamps and coins, but after sleeping out a couple of nights at

Billy’s aunt’s dairy and finding arrowheads in some nearby fields we

gradually spent more and more of our free time in this way.

Snubby was very rigorous in following the scout book guidelines

with regard to making a collection. He

made a separate 3 x 5 inch file card for each numbered item with an

outline drawing of the piece along with the time and place and

circumstances of each find. I

tended to follow this same procedure so long as I was with the scout

troupe but I was never as rigorous as Snubby was.

Billy and I gradually slipped away from involvement with the

scouts, but I think that Snubby stayed on and got his Eagle rating.

The point of all this is to say that I was never

rigorous with numbering my artifacts and keeping the proper records.

I did, however, come under the influence of others from time to

time who urged the practice on me and at times I made an effort to catch

up. But in general one can

never take the numbers on any of my artifacts as solid evidence with

regard to when or where it was found.

When I was much younger I believed that I could remember the

circumstances of acquiring each item, but that is no longer the case. Maybe my heirs and their friends can take a lesson from me

for there are times when I wish that it had been otherwise.

Billy and Snubby and I would often come to Snubby’s

room after a campout and a successful hunt and make our collection cards

there. We also noticed that

Snubby made an entry, however brief, in his journal every night before he

went to bed. I visited him at

his home many many years later and he told me that he had never lost that

habit. He had a foot or so of

space on a bookshelf covered with the collection.

He took one down and recalled a few entries recounting when Billy

and I had been in his room making file cards for some arrowheads that we

had just found.

We were not the only arrowhead collectors in town and

we soon learned a variety of locations where artifacts of various kinds

might be found. One of our

friends was Elmer E. who collected porcelains.

Bits of “modern” cups and saucers and dinner plates were often

found when we were looking for arrowheads… and visa versa from Elmer’s

viewpoint. We would each

gather up all such items and later get together and make the swap.

We also learned from fellow collectors, as well as

some people at the museum, the location of a half-dozen or so burial

mounds in and around Gainesville. The

museum had a number of restored clay pots on exhibit and the man who did

the restorations told us of several burial mounds where the shards were

more or less abundant. He

said that it was customary among many of the aboriginal people to break

all of a person’s possessions when they died and bury the debris with

the person. In some mounds

the dead person would be placed in the fetal position with the potshards,

etc., and covered with sand as fine and as white as could conveniently be

accumulated. In other mounds

the dead person would be placed face down and similarly covered with fine

white sand.

Snubby and I spent perhaps 2 or 3 Sunday mornings

digging in one of the larger burial mounds near the Kincaid Road.

We found a few potshards and a few bone fragments but it seemed

likely to us that others had been here before.

I saved the potshards and later offered them to the guy at the

museum, but he declined saying that he had more backlog than he could

reasonably deal with. On my

final dig at this mound I found a candy bar wrapper perhaps 3-ft below the

surface. Snubby did some

minor digging in at least 2-other mounds we knew of, but neither of us nor

anyone we knew ever found a stone tool in one.

I never dug in one again.

One time a kid I knew in high school gave me a couple

of arrowheads and told me that I could find more in his mother’s garden

if I would agree to be very careful of her vegetables.

I went to visit her soon afterward and she was quite agreeable.

Their home and garden were on the West side of Prairie Creek just

South of Newnan’s Lake. I

found no arrowheads in her garden, but I did notice some fish bones.

A path lead down to the edge of the lake and beyond.

The ground was mostly covered with vegetation of some kind, but a

land-terrapin (gopher, in Florida slang) had dug a hole near the path and

the mound of dirt it pushed out showed a number of fish bones and bits of

stuff that looked like charcoal from a campfire.

As a general rule the dirt removed from a gopher hole is a good

place to watch for artifacts, but one should be alert to the fact that

rattlesnakes often share the hole with the terrapins.

Back at the museum I shared this experience with the

pottery restorer and he told me that a number of arrowheads had been found

in that general area when the Hawthorne Road was paved there. He also told me that all of the dugout canoes on exhibit in

the museum were from the edge of Newnan’s Lake in that general area.

A severe drought a few years ago (1990+/-) also exposed a modest

explosion of dugout canoes buried in the mud and much speculation that

these had been made for commercial purposes by the aborigines.

A faint two-rut dirt road went through some heavy

undergrowth from the Hawthorne Road to Newnan’s Lake roughly parallel to

Prairie Creek and Snubby and I took the hike one day after we had looked

through the lady’s garden on the opposite side of the creek, finding

nothing but fish bones there. We

decided to set aside some time to dig in a patch of earth where the road

department had reportedly taken some fill dirt and the vegetation had not

yet reclaimed it fully. I

told my mother and father of this plan and they asked to be invited.

My father even made a small dirt sifter for the occasion.

When the day came we all rode our bicycles some 6-miles from our

home to the site, expecting to find Snubby already there.

He was not, so my father and I started digging and sifting while my

mother took a walk through the scenery.

We started finding fish bones and small bits of charcoal

immediately and after a short while we had a beautiful arrowhead and a

small piece of bone that looked like, possibly, deer antler.

Unlike the human bones found in the white sand burial mounds that

were soft and chalk-like, this bone was dark brown and hard.

The dirt here was also black and hard and full of small roots.

Something the pot-restorer at the museum said led me to believe

that such earth was entirely unsuitable for burying family members.

Snubby showed up in the middle of the afternoon

saying that he had been pressed into service unexpectedly by his employer

and this was why he was late. By

this time my father and I had sifted the surface over a couple of square

yards and had 3 or 4 whole arrowheads spread out on a log nearby for his

inspection. He was duly

jealous, but he soon found several beauties himself and was in great

spirits. I am not absolutely sure, but I think he found a very well

shaped bone awl on this occasion, probably made from deer bone, along with

several pieces that were quite clearly deer antler.

I have a number of these bone awls and I am unaware of any others

being found anywhere else. Again,

large numbers of fish bones and bits of charcoal were found however deeply

we dug. My guess is that we

didn’t go deeper than a few inches on this occasion.

I can’t recall any occasion where either Snubby or I worked over

this ground for an hour or more and failed to find some evidence of

ancient human habitation, including human bones on occasion.

The general opinion at the museum was that these bones were strong

evidence of cannibalism because aboriginal people would never bury their

family members in black muck beside fish bones, deer bones, and the

charcoal from campfires.

One of the members of the scout troupe I had been

friends with had gone arrowhead hunting with us a couple of times, but

then he told me that he was simply too busy otherwise and gave me the

half-dozen or so arrowheads he had gathered so far.

He and I were in the high school band and orchestra at this time

and I knew his 2-sisters from those activities as well.

Their father, an Army Chaplain, had recently been assigned to the

ROTC functions at the University. One

day, after a very productive dig at the Prairie Creek, I dropped by these

friend’s house to share my finds of a couple of arrowheads along with a

rare potshard or two and a couple of bits that were clearly human bones.

Their father came over to have a closer look and, after hearing my

explanation of how I happened to have them, he told me that I was nothing

but a goddamned grave robber and that I was not welcome in his house.

His children were still as friendly as ever, but I’d had

confirmed some suspicions as to how some of the other local folks might

view my hobby. I then tended

to keep a low profile in this regard.

I turned 18 in 1944 and was fortunate to find myself

accepted in the US Navy RADAR School.

This lasted about a year. The

war was over by then, but many people in high places expected war with the

USSR to break out momentarily. I

was sent to Arizona where military aircraft were being “pickled”

(preserved) in the desert to be ready for action should the need arise.

I soon made the acquaintance of a lady archaeologist at a museum in

Phoenix. She had a need for

volunteer diggers and I was delighted to serve in that way when I had

liberty on the weekends. She

was in charge of the excavation of a pre-Columbian site on the grounds of

a hospital in Phoenix that was being expanded.

I worked some at the site for perhaps 3 or 4 weekends with the

bulldozers getting closer and closer.

The site had once been an adobe living quarters… at least some

“walls” were apparent… but the earth was solid everywhere.

Mostly well-decorated potshards were found, but there were several

small (2-inches across+/-) baked clay items that were like a child’s

replica of a face as well.

Most impressive, however, were several turquoise

“amulets”. These were

beautifully carved in the likeness of animals like coyote, a bird, and

maybe a lizard. I can not

recall the precise details, but I can report that the archaeologist was

most excited to find them. She

had seen other examples, but these were the first that she had found

personally and she was most excited by the size (2-inches more or less)

and quality of the work. As I recall, there were 3 or 4 in total number and at least

one was whole while another was broken.

When I first met this lady I told her about hunting

for arrowheads in Florida and asked her about good places where I might

look locally. She told me in

no uncertain terms that she didn’t approve of amateurs horning in on her

territory in any way. The

damage done to “real” archaeology by “pot hunters” was nothing

short of scandalous and she and her professional and licensed colleagues

were very active in trying to get laws passed to make amateurs into

criminals as well. The bulldozers took out the “pueblo” before the

archaeologist had completed her excavations, but overall she seemed quite

pleased with what she had found. We

parted company with the understanding that I would probably be available

if or when she had further need for a digger, but she never called.

In the meanwhile I occasionally found myself on

perimeter patrol duty with the Navy.

There was a heavy duty chain link fence topped by barbed wire

around the base and the Navy was always on the alert for evidence that

thieves might break in and steal scrap metal or other valuables from the

aircraft. The 2-rut dirt road was barely evident and there was plenty

of cactus-free surface to be seen beyond the road.

I found it to be ideal for hunting artifacts.

I took my time and wandered as far into the surrounding territory

as I could while still keeping my assigned time schedule. I found several decorated potshards and a few small

arrowheads that seemed to be made from a very poor grade of obsidian as

well as a half-dozen “beads” made of bits of seashell.

Most impressive to me, however, were 2-stone “axes” (clubs?)

that seemed to be made by abrasion somehow.

One was reasonably well polished, while the other was more roughly

hewn somehow. I kept these

finds to myself in view of what the archaeologist had told me.

I was discharged toward the end of summer in 1946 and

found that I had some 4 or 5 weeks of free time before classes started at

the University, assuming that I would be accepted… a far from certain

proposition.

I camped at the Prairie Creek site around the clock

for several days until heavy rains forced me out.

I cleared the brush away from several patches perhaps a couple of

square yards each and excavated each about a foot deep. These patches were spread out from Hawthorne Road to the lake

and I got the distinct impression that this whole area had been a busy

human habitation for a long time… perhaps several centuries or more.

I found arrowheads, deer antlers, bone awls, a few crude and thick

potshards, a couple of antlers with holes as if for use as a pendant, fish

bones and charcoal in abundance, and several human bones such as jaw,

finger, eye socket, etc. The

human bones as well as the antlers and awls were brown and very solid as

if, perhaps, preserved by the hard black muck.

I certainly suspected cannibalism.

(I never found a thin or painted potshard there like those found in

abundance at the burial mounds).

I also dug deep in a corner of each of these sites to

see if what I had found early on was a general finding that there was a

layer of fine white sand below the mud.

This was the case everywhere I looked and I assumed that this layer

was once the shore of the lake and that perhaps the lake had been spring

fed long ago in geologic time. It

was certainly creek-fed at this time and the water was always very murky

during rainy weather when a dozen or so creeks drained their muddy water

into it.

I rarely found any human artifacts in this white sand

layer, but I did on occasion. Later

that year, in fact, I found a totally remarkable flaked tool some 3-feet

below the surface and roughly a foot into the white layer.

This is the finest example of the art of

‘flint-knapping’ I am aware of and it presents me with another small

mystery I have yet to resolve in my own mind.

The Number 284 is a consequence of my association with Barry.

Barry was a Professor (? Maybe Assistant Professor?) at the

university. He taught a

course in sociology and a lady friend of mine was his student. They were both quite interested in my hobby and I took them

to the Prairie Creek site as well as several other likely places.

Barry became so interested in fact that he read several books on

archaeology from the library and the following year he offered a class in

that subject. And he ragged

on me to bring my collection cards and notes up to speed, which I did up

to a point. I also gave him a

box full of potshards, bones, and arrowhead halves and fragments, but none

of my more-or-less whole ones. He

had these items on display in a glass case in his classroom when I left

the university in 1950 and went to graduate school in Ohio, but neither he

nor those artifacts were to be found when I brought my bride to see them

in 1952. I will not leave my

stuff to a museum or anyone other than my children.

What they do is their business.

To summarize, and getting back to my small mystery of

the bones I found on Starvation Hill, I do not believe that those bones

were placed there in anything like a formal burial.

I believe it is highly likely that the person died and decomposed

on that spot and that neither his family nor the people with whom he did

business ever realized what had happened to him.

I also think it highly likely that he (or she, but not likely) was

a merchant in the flaked stone tool trade.

I once saw a TV presentation about a study of the commerce in raw

stone used for making flaked tools in Europe.

The claim was made that at least some of the various quarries where

‘knappable’ stones were to be found could be classified by the color

and the trace elements in the stone and there was considerable evidence

that long distance commerce in those stones was very likely. I find it very likely that my arrowhead merchant was aware of

the sinkholes in the area and the knappable stones to be found there along

with the occasional quartz piece.

I welcome and encourage other scenarios to account

for my evidence.

Rene Rogers, Sunnyvale, CA

ageseeker1@juno.com 408

243 2753

|