|

|

||

| New York: D. Van

Nostrand Company, 1949, 1st edition, written by members of the technical

staff of Bell Telephone Laboratories with an introduction by Mervin J.

Kelly, 6 1/2" x 9 1/4", 1042pp, illustrated with photographs,

drawings and diagrams. Original light blue cloth, dust jacket worn at

edges and corners, previous owner's name on fep.

"This first unified and complete presentation on Radar Systems and Components - from basic theory to final application - was made possible by the cooperative effort of 28 members of the technical staff of the Bell Telephone Laboratories. During World War II the Bell System played a larger part in the radar program, from research through production, than any other industrial organization. The men directly responsible for this contribution now explain the products of their research and development from the standpoint of structure, operation and use. They deal not only with radar's historical developments, but with present applications as well." |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

by Victor J. Young |

||

|

"The First 25 Years of the Naval Research Laboratory" by A. Hoyt Taylor. This is a wonderful book that documents the first 25 years of the lab between 1923 and 1948. The book was published by the Department of the Navy, Office of Naval Research. For those not familiar with the Lab, it was established as a department of invention and development for the Navy. Basically, the lab is the techies of the Navy. Thomas Edison was the Chairman of a board of consultants for the labs, the Naval Consulting Board of the United States. Later members of the board included Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Maj. Gen. LeJune and other notables. The projects the Labs undertook in their first 25 years would be too numerous to list here. Some of the more interesting projects included radio transmission, radar, torpedo fuel, radio controlled aircraft, sonar, camouflage, infrared & ultraviolet devices, chemical warfare, atomic power, lubricants, and others. This book is basically a personal history of the Labs from the viewpoint of the author who was employed there. It contains a number of photos of the facilities and projects. It makes fascinating reading on how World War II changed the thinking of the Navy and just how the labs grew and expanded, not to mention the insight on projects like radar and sonar. The book is some 75 pages long with a soft cover and dual staple binding.

|

||

|

|

||

|

||

|

Ground Radar Systems of the Luftwaffe 1939-1945, by Werner Muller. 48 Pages. Softbound. This book gives descriptions and a photographic account of the ground radar systems of the Luftwaffe used during WWII. |

||

|

Alkaline Earth Oxide Cathodes for Pulsed Tubes by Coomes, Buck, Eisenstein and Fineman. Hardback book comprised of photographs of pages of a 1946 report "933" from the Radiation Laboratory , MIT, Cambridge, MA.117 pages.

|

||

|

Five Years at the Radiation Laboratory

Five Years at the Radiation Laboratory ( Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1947. 204 pp. 4to- between 9¾" - 12" tall). "Presented to Members of the Radiation Laboratory by Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1946" Heavily illustrated work has a yearbook format. This Volume will entertain you and present a flavor of what life was like at the RadLabs. One interesting this is there are spots where there are blank pictures because they were pulled at the last minute for security purposes. Remember, the ware was over, but some of this development was still highly classified! Background Information from MIT's Radiation

Laboratory of Electronics |

||

|

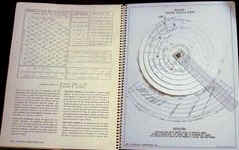

A Few Sample Pages

|

||