I

recently came across a short article about a deaf inventor who

lived and worked in Brookline at the beginning of the 20th

century. I thought I'd do some quick research and a brief

write-up.

I

recently came across a short article about a deaf inventor who

lived and worked in Brookline at the beginning of the 20th

century. I thought I'd do some quick research and a brief

write-up.Little did I know how complex and interesting the story of William E. Shaw would turn out to be.

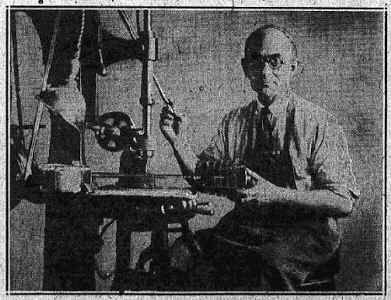

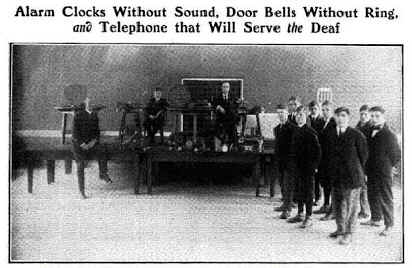

Shaw, who had been deaf since the age of 5, designed and built a series of special electric devices -- telephones, doorbells, alarm clocks, burglar alarms, and more -- all for use by those who could not hear.

His work won praise from Alexander Graham Bell and an invitation from Thomas Edison to work at Edison's laboratories in New Jersey. Shaw and his wife and son were also at the center of a controversial custody battle that revolved in part around the rights and abilities of deaf parents to raise hearing children.

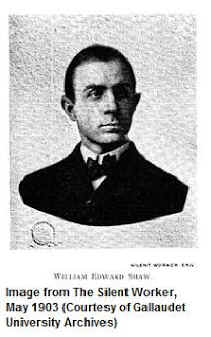

William Edward Shaw was born in St. John, New Brunswick, Canada in 1869, the son of a sea captain and his wife. Shaw lost his hearing after a bout of spinal meningitis when he was 5, and his father took the boy to sea with him in the hope that a change in climate would help his recovery.

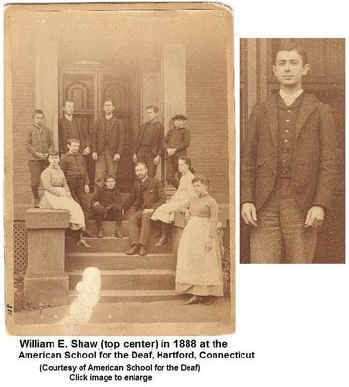

After the father died in 1877, the family moved to Portland, Maine. Shaw was educated there and later at the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut. After graduating in 1893, he worked at a carriage factory and then at Anchor Electric in Boston and the Holtzer Cabot Electric Company in Brookline, moving to Brookline before the turn of the century.

It was in his home laboratory at 12A Linden Street that Shaw worked on many of his inventions, including:

- the "talkless telephone," which enabled deaf people to send messages over a telephone line by typing on an ordinary typewriter which caused light bulbs with letters and numbers on them to be lit up at the other end of the line.

- a doorbell that

activated not a chime, but flashing lights (different colors

for the front and back doors), an electric fan pointed at the

bed, and other kinds of soundless alerts.

- an alarm

clock that

agitated the sleeper's pillow to wake them up.

- a baby monitor that alerted parents to the movements of a restless baby by flashing lights or shaking the parent's pillow.

Image from Popular Science, November 1924

Alexander Graham Bell, whose research on hearing and speech -- both his mother and wife were deaf -- led to his invention of the telephone, met and corresponded with Shaw. In a 1904 note, Bell wrote to Shaw:

"I have always been greatly interested in your inventions for the Deaf, and trust that the future may bring you continued success in the pursuit of your worthy inventions." (See an image of the note.)

There is no indication that Shaw's inventions were produced commercially or widely adopted. (His only patent appears to have been for an arcade shooting game in which the target would light up when hit while everything around it went dark.) But the inventor and his efforts garnered widespread attention with numerous articles in Boston-area newspapers as well as theNew York Times, the Washington Post, and other publications around the country.

He was also an advocate of both electrical knowledge and the deaf community, giving demonstrations that raised money for programs and organizations for the deaf and promoting the inclusion of electrical work in the curriculum of schools for the deaf.

The custody case involving Shaw began in 1907. Shaw's first wife Lucy, who was also deaf, had died in 1902 soon after giving birth to their son, William Jr. The child, who was not deaf, went to live with his maternal grandparents in Boston. Shaw remarried -- his second wife was also deaf -- and in 1907 took back his son over the objections of the grandparents. Brought before a judge in probate court, the case drew wide attention with more than one hundred members of the deaf community present in the courtroom.

Several witnesses, including an Episcopal bishop who worked with the deaf community, testified that deaf parents could not raise a hearing child without having a negative impact on the child's development. Shaw was also attacked personally. Witnesses -- including his own mother and several of his siblings -- testified that he had a violent temper. But other witnesses, including his landlady, co-workers, and another sibling, testified on his behalf disputing the attacks on his character and praising his affectionate and loving demeanor with his son.

Both sides asked Alexander Graham Bell to support their case, but Bell -- saying he did not know Shaw well enough personally -- declined to get involved.

Shaw himself took the witness stand, speaking -- as had other witnessses -- through a sign language interpreter. The judge ruled in Shaw's favor, and the boy stayed with the inventor and his wife.

Six years later, William Jr. , then 10 years old, stayed with his grandparents again when Shaw's second wife became ill, and Shaw had to go to court to get the boy back again. After this second courtroom victory, he wrote:

"It is partly for the sake of the deaf in general that I have fought so hard. Law is law and it is the duty of the deaf to defend their own rights and fight for them if necessary."

Shaw's son, who was known as Willie, helped his father in his electrical exhibitions. He later became a seaman like his grandfather.

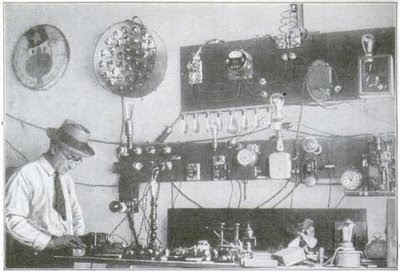

William

Shaw and his son at a demonstration at a New Jersey School, 1914

William

Shaw and his son at a demonstration at a New Jersey School, 1914Image from The Silent Worker, April 1914

(Courtesy of Gallaudet University Archives)

After leaving Brookline, William Shaw lived in Dorchester and then in Lynn, where he worked for General Electric. He later accepted Thomas Edison's invitation to come work for the great inventor and stayed at the Edison labs in New Jersey for five years.

Shaw returned to Massachusetts in the 1920s and continued his work. He was profiled by the Boston Globe at his Cambridge home and lab in 1924. He returned to Brookline in 1934 and lived at 9 School Street for the rest of his life. He died July 1, 1949 at New England Deaconess Hospital.

For more on William E. Shaw, see the following:

- A Deaf-Mute Electrician (The Silent Worker, May 1903)

- Deaf

and Dumb Electrician (St.

John Daily Sun. August 22, 1904)

- Mr. Shaw's Victory (The Silent Worker, May 1907)

- "Talkless

Phone" Invented by Deaf Mute (Popular

Science, November 1924)