Albert Ghiorso dies at 95; engineer played crucial role in discovery of 12 elementsHe designed many of the accelerators and detectors that made it possible to produce and identify the heavy, short-lived radioactive elements beyond uranium, the heaviest found in nature.

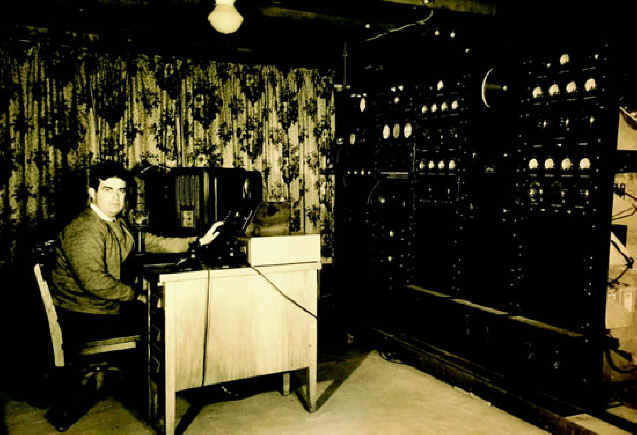

Albert Ghiorso, a Berkeley engineer who played a crucial role in the discovery of 12 elements, more than any other scientist, died Dec. 26 at his home near the UC Berkeley campus. He was 95 and died of heart failure after a minor fall near his home. A talented engineer, Ghiorso designed many of the accelerators and detectors that made it possible to produce and identify the heavy, short-lived radioactive elements beyond uranium, the heaviest found in nature. Ghiorso initially worked under physicist Glenn Seaborg on World War II's Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb, then at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. But eventually he came to be seen as Seaborg's equal in many ways. "It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of Ghiorso's work on the field of nuclear science and nuclear chemistry in particular," said physicist Peter Armbruster, co-discoverer of elements 107 to 112 at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia, which relied on techniques developed by Ghiorso. "Anyone familiar with the details of the challenges will appreciate the critical value of Ghiorso's brilliant experimental mind and his resourcefulness in solving the problems." Ghiorso was born in Vallejo, Calif., on July 15, 1915, and grew up in Alameda, where he built radio circuitry and developed a reputation for making long-distance radio contacts. After receiving his bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from UC Berkeley in 1937, he went to work for a small firm called Cyclotron Specialties Co. in Moraga, where he built the first commercial Geiger counter. When the war broke out, Ghiorso decided to seek a commission in the Navy and asked for a reference from Seaborg, whom he had met at Berkeley. Instead, Seaborg invited him to join a secret project at the University of Chicago, which turned out to be part of the Manhattan Project. Seaborg's team had secretly discovered plutonium, element No. 94, and Ghiorso helped develop instruments and techniques to purify it. In 1944, Seaborg decided to extend the search to higher atomic numbers, asking chemists Ralph A. James and Leon O. Morgan to irradiate plutonium and send the samples to Chicago for Ghiorso to analyze. By identifying characteristic alpha-particle emissions, Ghiorso found curium, element 96, and americium, element 95. After the war, the team returned to Berkeley, where Ghiorso developed new, more sensitive detectors to isolate and characterize the newly created elements. In December 1949, the team found element 97, berkelium, and in February 1950, element 98, californium. Ghiorso described the discovery of the next two elements as "absolutely unexpected and out of the blue." In November 1952, a large thermonuclear explosion was set off on Eniwetok Atoll in the South Pacific. Scientists measured an unexpectedly high neutron flux from the explosion, and Ghiorso suspected that meant new elements had been created. He persuaded the team to acquire paper filters from airplanes that had flown through the radiation cloud. Within a few days, they had found einsteinium, element 99. In January 1953, they found fermium, element 100, that had been deposited in coral by fallout from the test. In February 1955, the team created mendelevium, element 101, by bombarding einsteinium in the Berkeley cyclotron. The element was so short-lived that extraction of the element from the foil target was performed in the back seat of Ghiorso's Volkswagen as he sped up the hill from the cyclotron to his laboratory. Producing heavier elements required a larger accelerator, so Ghiorso and his colleagues designed the Heavy Ion Linear Accelerator (HILAC), which began operating in October 1957. Using it, they found nobelium, element 102, in 1958; lawrencium, element 103, in 1961; rutherfordium, element 104, in 1969; dubnium (also known as hahnium), element 105, in 1970; and seaborgium, element 106, in 1974. Ghiorso was named director of the HILAC in 1969. To reach higher elements, Ghiorso designed an accelerator called the Omnitron that would have accelerated all elements up to uranium to high energies. Funding for the accelerator was blocked by the Vietnam War, however, and the discovery of new elements shifted to Europe and Russia. Ghiorso also invented the Bevelac, which combined the HILAC and the Bevatron to accelerate heavy particles to velocities close to the speed of light for research in high-energy physics, nuclear chemistry, biology and medicine. Ghiorso was preceded in death by his wife, the former Wilma Belt. He is survived by a son, William, who is an engineer at the Berkeley lab, and a daughter, Kristine Pixton of Vestal, N.Y. |

|||||||||||||||||||

A scientist who was truly in his element making discoveries

January 21, 2011

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| THE

TRANSURANIUM PEOPLE - The Inside Story

http://www.worldscibooks.com/etextbook/p074/p074_preface_2.pdf |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

“NOTES

FROM REGINAL TIBBETTS: 1.

REGINALD TIBBETS RPE (ENGINEER): HE RAN THE INTERCEPT PROGRAM FOR UNITED

PRESSS, OFFICE OF WAR INFORMATION, AND THE U.S. NAVY.

HE INTERCEPTED JAPANESE TRANSCRIPTS DURING WORLD WAR II. HE

BROKE THE CODE

SO ...THE U.S. WAS ABLE TO KILL YAMAMOTO WHO HAD PLANNED TO BECOME EMPEROR 2.

CYCLOTRON SPECIALTIES COMPANY “He

got permission from Ernest Lawrence to use the name “Cyclotron”. This

company made test instruments for the atomic bomb and parts for the bomb.

The Geiger counter was built in Moraga. Ernest Lawrence came to the

Tibbetts house several times. Reginald Tibbetts also knew Glen

Seaborg, Kennedy, and Salsburg. Many of the parts for the bomb and

the Geiger counter were made by individuals then sent to Moraga and

Reginald Tibbetts helped to assemble them. All the parts for the Geiger

counter were bought in the San Francisco Bay Area in small amounts so it

would not be suspicious and paid for in cash. Reginald described how

he use to go shopping for parts with $20,000.00 cash in his pocket.” From:

Ed Sharpe [mailto:COURYHOUSE@aol.com]

|

|||||||||||||||||||

https://books.google.com/books?id=eYxzHPtkqaIC&lpg=PA69&ots=F1lXkieHJV&dq=Geiger%20counter%20was%20built%20in |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Title: Geiger Counter SMECC and USGS are both looking for more information on this unit. Drop me a line at info@smecc.org --Ed

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Instrumentation Between Science, State and Industry - Google Books Result | |||||||||||||||||||