|

The St Louis Relay Service

The St Louis relay service (I believe the first one in the nation)

started in a home which served as a wake-up alarm for hearing people.

Imagine that! Racking my poor head, I'm thinking that around 1968, John

Woodard of Western Union suggested I make a personal visit (the home was

just a half mile away) and bring up the idea of a relay service for the

deaf. The manager (probably the owner) agreed to give it a try. Two

dollars per deaf family per month to use it, I think. Service limited to

normal business times and did not include weekends. There were about ten

to fifteen deaf families wanting to give it a try so that amounted to

about thirty dollars per month, not that cheap way back in 1968. Well,

we were dumfounded over the escalating use of the service after only a

few months. The manager called me and said how sorry he was to inform me

that unless we come up with more money he would have to cancel the

service. By that time, a non-profit organization for suicide prevention

learned of the new relay service and volunteered to try it. So, I moved

the equipment over there and service was resumed. Many of the deaf

families said how much they relied on it for important calls and

obviously the service will have to be expanded. By that time, I believe

in 1969, the state of Missouri was alerted of this kind of service

(quite a few hearing people called to alert the state of such an

important service operated only by volunteers). The service went on for

about a year and finally, the state set up something (how dim my memory

is !!!) which was not much better than the volunteers, however, it was a

bit more dependable. Around that time, the East Coast got started with a

relay service in just a few states. For a long time, services were

intra-state only and the pressure built up at the FCC to broaden the

service to nationwide. After the Americans with Disability Act passed in

1990, all fifty states had continuous (7 days, 24 hours) interstate

relay service, FINALLY !!

Paul Taylor

Converse Communications Corporation

(formerly Converse Communications Center) (CCC) as a non-profit tax

exempt organization was first established in the USA in 1974 to provide

telecommunications access for Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing people living in

Connecticut. The state-wide service began on February 11, 1974,

providing telecommunications relay service, 24 hours a day, 365 days a

year. William "Bill" Yoreo and his wife, Grace were the

directors of CCC.

While

they worked with deaf people at a local church, Bill and Grace realized

that the vast majority of the deaf community were without telephones and

TTYs. They obtained a grant to distribute TTYs to the deaf and hard of

hearing population in Connecticut. David, their son joined them to run

their business. While

they worked with deaf people at a local church, Bill and Grace realized

that the vast majority of the deaf community were without telephones and

TTYs. They obtained a grant to distribute TTYs to the deaf and hard of

hearing population in Connecticut. David, their son joined them to run

their business.

CCC eventually grew from their home to

relocate to a building within the American School for the Deaf campus

and then moved to an office building in Bloomfield.

At the same time, CCC also operated

the captioned TELENEWS Service to broadcast on all five public

television channels and provided live AP News, Sports, and Stock Market

Reports. TELENEWS provided items of local interests, a calendar of

events, and weather reports.

In addition, CCC manages the TTY Loan

Program, along with their popular state-wide TTY directories, which are

updated on an annual basis. With the changing business environment and

the entry of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1993, CCC became a

partner with Relay Connecticut, providing the TTY Loan Program for deaf,

hard-of-hearing and speech-disabled people living in Connecticut.

Currently, CCC distributes TTYs to the

deaf, hard-of-hearing and speech-disabled people in Connecticut. Repair

services are included in this program. TTY directories are generated on

an annual basis.

Additionally, CCC sells a large

variety of custom-made equipment for telecommunications and

accomodational needs, ranging from TTYs, Alarm Clocks to Doorbell

signalers and Payphone TTYs.

Please visit CCC's

web site for information.

Directions to:

Converse Communications Corporation

34 Jerome Ave

Bloomfield, CT 06002-2463

|

|

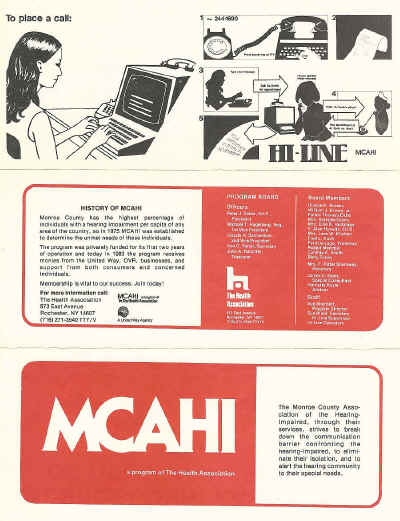

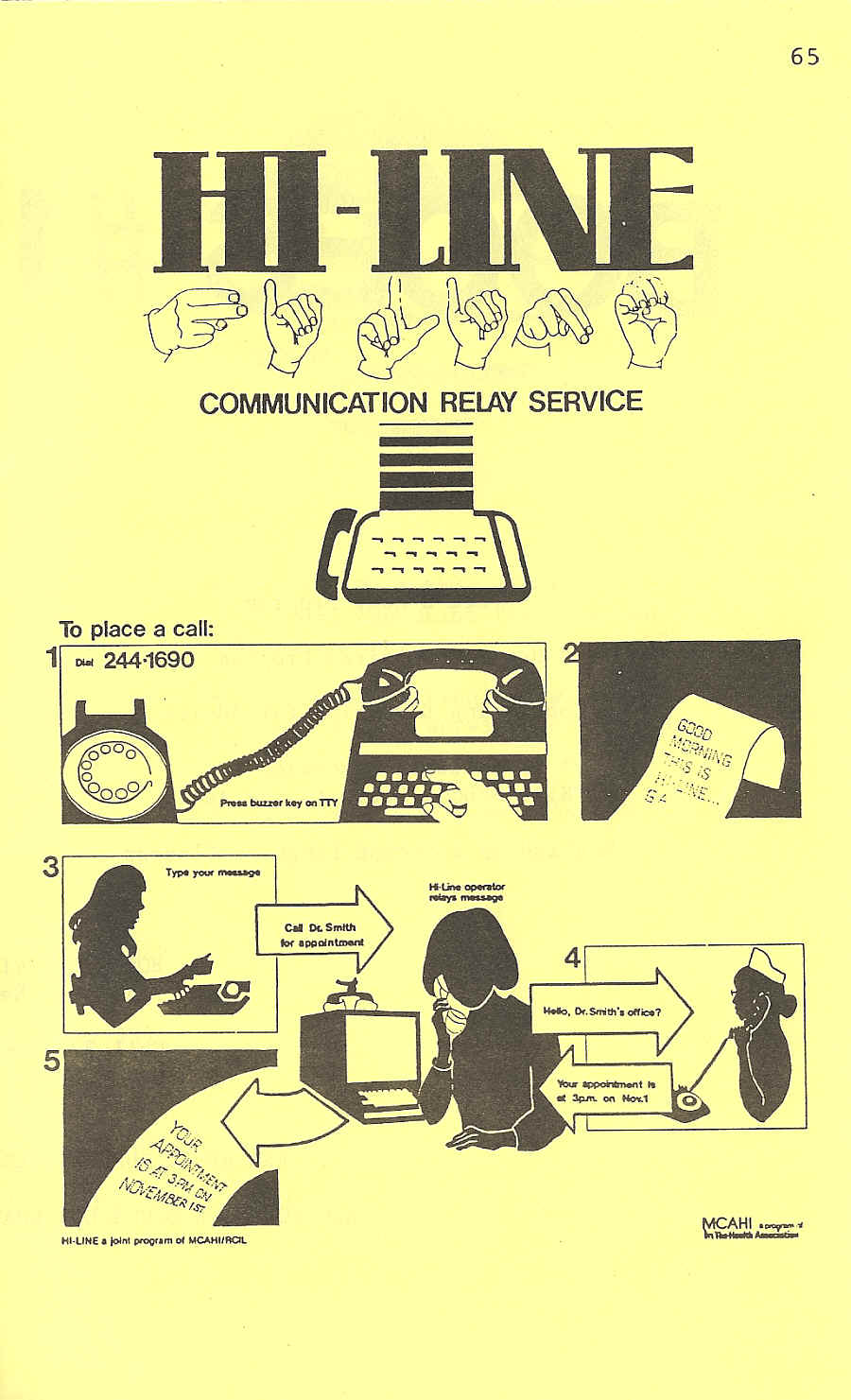

HI-LINE RELAY

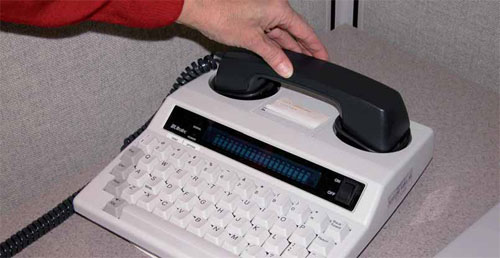

Lester

Zimet had HI-LINE's Phonetype 5 - Look we brought it to life and

it typed to us!

Message is in ROM in the modem... It is like a voice... for

the past...

Hi-Line is a third party relay service for the hearing

impaired. Through Hi

Line the hearing impaired person has a portion of normal access to the

tele

phone as the hearing person. Hi-Line was started after a direct request

was

received from the President of the Rochester Tel-Com Association of the

Deaf

stating:

"The greatest need of the hearing impaired person is a third

party answering service which will enable the telecommunication

device (TTY/TDD) user to communicate his/her everyday needs."

Thus, in February, 1979 a volunteer relay service began. In June, 1979

CETA

funding was obtained and a paid staff was hired. In October, 1980

Hi-Line

became a joint program of the Monroe County Association for the Hearing Im

paired (MCAHI) and Handicapped Independence Here, now named the

Rochester

Center for Independent Living (RCIL), funded by the Office of

Vocational

Rehabilitation (OVR) and the United Way of Greater Rochester.

Currently the hours of the Hi-Line Relay Service are as follows:

Monday - Friday: 7 am - 9 pm

Saturday: 9 am - 5 pm

Sunday: 10 am - 2 pm

The service is generally closed for all recognized holidays (ie:

Christmas,

Thanksgiving, Labor Day, etc.).

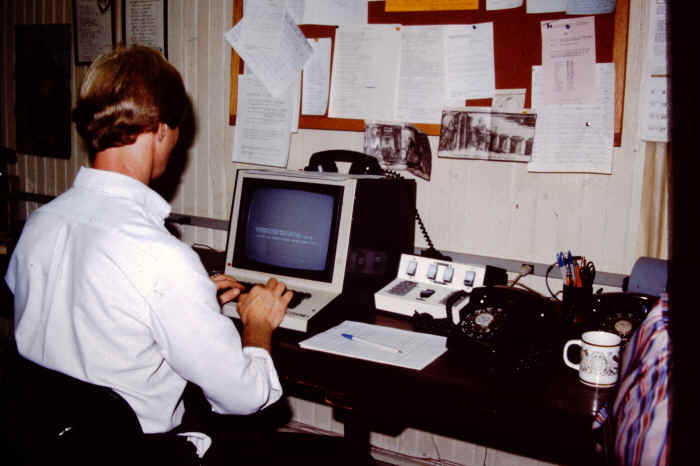

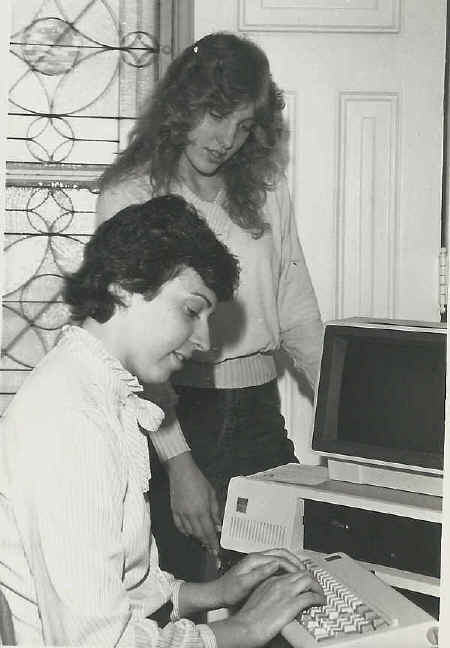

C- SMECC From the Paul and Sally Taylor Collection at

SMECC

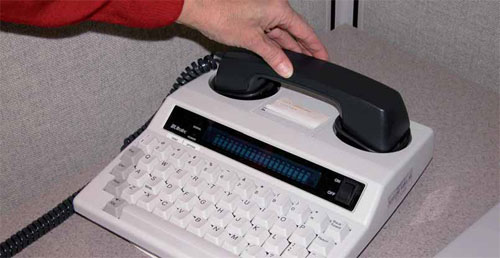

C-Phone In use

Sally Taylor tells us - "In this

photo the C-Phone was used by a relay service set up in Rochester, New

York... Called the Hi-Line Answering Service, it operated for

several years with limited hours, such as from 8 to 5 Monday through

Friday, and no weekend calls. This service was managed by the Monroe

County Association for the Hearing-Impaired. Eventually Paul pushed for a

24/7 service, and it went nation-wide, thanks to the signing of the ADA in

1990."

| The Deaf

Insurrection Against Ma Bell Harry G. Lang states - "The

burden on local services was overwhelming. Hi-Line Relay Service

in Rochester, for example, was handling 163,497 calls with only

four operator positions . There was a blocking rate (TTY callers

getting busy lines) of 30 percent)" |

ROCHESTER ADVOCATE

NOVEMBER 1979

Of interest to all hearing-impaired

persons is the H-line answering service

(244-1690), a new program of Monroe

County Association for the Hearing

Impaired. Ye editor has used it and found

it very helpful in talking to a hearing friend

who does not have a teletypewriter. The

Hi-Line operates from 9:00 a.m. to 9:00

p.m. Mondays thru Fridays. It can be used

by hearing people when they need

assistance in reaching their hearing

impaired relatives or friends.

ROCHESTER ADVOCATE

NOVEMBER 1982

A fund-raising carnival was held in

the RSD Gym on February 18. Hosted

by various Rochester organizations for

the deaf, the funds raised contributed to

sustaining the Hi-Line Telephone Service

for the Hearing-Impaired in

Rochester.

Alumni Notes -

A Carnival held on February 8, 1983,

was very successful in raising over

$1000 for the Hi-line communication to

continue its useful services to the

hearing-impaired members. The idea of

a carnival was suggested by 15 Rochester

area deaf organizations. The carnival

lasted from 7 P.M. to 11 P.M. and held all

sorts of amusements. Helen Richardson

won the top prize of $250 and Jenny

Clupper (daughter of Diane Clupper)

won the second one of $150. Involved in

much of the work were Dorislee Grann

and John Ratcliffe

|

Chapter 26: The Short History of Text Telephones

-p238-

Chapter 26: The Short History of Text Telephones

Stephen von Tetzchner

When Bell invented the telephone in 1876, this represented a crucial step in the history of telecommunications; the introduction of the telephone made it possible for the general public to use their own voice to communicate over a distance instead of having to write down messages and ask a telegraph operator to relay them to the other part. For some people, that is, for those who cannot hear or speak, the general development implied a more difficult situation because they were unable to use telecommunication in the same manner as others. They were not able to take part in many new developments in society, because they lacked the possibility of direct communication with people at other geographical locations. While society at large changed, the communication patterns of deaf and speech impaired people remained very much the same.

However, it is not, of course, the development of audio telephones in itself that should be criticised, but the lack of interest for the situation of those who could not use this service. After all, the first telecommunication service, the telegraph, was based on transmission of letters, and from the perspective of speech and hearing impaired people, it seems rather surprising that it should take almost one hundred years before text communication was made available for personal use.

The short history of the text telephone, compared to the history of the audio telephone, started in the USA, where the first text telephone, or a least an approximation of it, was "invented" in 1964. As has often been the case with new developments for, and movements of, disabled people, Europe was somewhat later on the stage than the USA. But equally typical, Europe has caught up, and today, several European countries have better equipment and services than the USA.

1 The First Text Communication Devices: The USA

The implementation of personal text communication devices was mainly a result of expensive equipment becoming obsolete, combined with some creative intervention. In the beginning of the 1960s, the teletypewriters (telex machines) developed early in the 1930s for document transmission, were beginning to be replaced with more modern ones. In 1964, Robert Weitbrecht developed an acoustic coupler that allowed two teletypewriters (usually called TTY) to communicate over the telephone network (Bellefleur, 1976).

The teletype machines were huge, weighed around 25 kilos and were not well suited for a living room. The conversation was written on paper, which is probably the reason why deaf people have got into the habit of demanding prints of conversations. There was also a range of user-hostile features, such as independent carriage return and linefeed, so that when the user forget to do both operations, there would be a black mark at the end, or a new line of text over the previous one (Geoffrion, 1982). But such matters were of minor importance for the users compared to the fact that at last they had obtained access to personal telecommunication without having to use an interpreter.

From 1964 to 1968, only 25 machines were operational, but from 1968 to 1975, the number increased to about 5 000 units. Most of them were of the old type which was designed some 40 years earlier. Little was done to modernise the equipment, and although for the last ten years there has been talk about moving away from the 5-bit Baudot code not used by few others in the world today (cf. Castle, 1981; Pflaum, 1982; Middleton, 1983), it is still this standard that is in common use (there are couple of devices which can communicate with both ASCII and Baudot). There have, of course, been newer models; in the 1970s, new, instead of reconditioned equipment came on the market, and in 1980, there were 10-15 different manufacturers (Castle, 1981). New models are usually called TDD (telecommunication devices for the deaf). Some of these had hard print, others had small displays, as well as automatic answering facilities, but in general, both functionality and technical standards are the same as the out-of-date units 30 years ago. The typical TTY today has a one or two line display with 32 characters and a transmission rate of 45,5 bit/s.

It has been claimed that more modern equipment would have been more expensive, and that this was the reason why Weitbrecht developed the TTY on out-of-date technology. Deaf people could get reconditioned surplus teletype equipment relatively cheap; that is, initially the average price was $ 2 000, which by 1982 was reduced to $ 1 000 and to $ 500 in 1987 (House document No. 9, 1988; Levitt, 1982). Many deaf people belong to low- income groups, and even at this price, they found the units hard to afford, and for example in the state of Virginia, in 1987, only 27 per cent of potential users had a text telephone. This led to an initiative to provide free text telephones to those who could document a need (House Document No. 9, 1988).

On the other hand, the Baudot standard is extremely slow, and the user may lose on the swing what he or she gains on the roundabout. The use of low cost TTY machines represented a major step forward, but at the same time painted deaf people into a corner by excluding them from communication with other possible text communication devices, that is, in the USA, computers (Middleton, 1982).

A factor that has contributed to conserving the use of old-fashioned technology is probably the fact that in several American states, telecommunication equipment is provided by the telecommunication companies at the same price as ordinary equipment. For example, in 1979, Senate Bill 597 became law in California, requiring telephone companies to provide text telephone devices to certified hearing and speech impaired people free of charge (Pflaum, 1982). While applauding this development, one should consider the risk that telephone companies do not want to develop new equipment if this means higher distribution costs later.

1.1 Services

The first services to appear were emergency services where a call could be directed to a hearing volunteer with a TTY who would then relay a message to the police, hospital or fire brigade. In 1980, Bell Telephone Systems installed a special nation-wide toll-free TDD number that allowed TDD users to get assistance from a telephone operator (Castle, 1981).

The first relay service was established in St. Louis in 1969 as part of a private answering and wake-up service, serving 20 deaf families. The service was discontinued after six month because the time it took to relay a conversation was much longer than expected. A new service was started up in 1972 "when a volunteer organization offered services which, even to this day, have been woefully inadequate in meeting the telephone needs of the hearing impaired population in St. Louis" (Taylor, 1989, p. 13).

A number of similar small operations appeared in the 1970s; some larger ones were also established, such as the Hi-Line Relay Service of Rochester, New York, which handled 163 497 calls in 1987. In spite of the large number of relayed calls, with only 4 operators, the blockage rate was 30 per cent (Taylor, 1989). There is no doubt that the lack of nation-wide, or at least state-wide, services have severely hampered the possibilities of deaf and speech impaired people to make full use of telecommunications.

The first state-wide service was opened in California in 1987, followed by Arizona and Washington. In its first month, January 1987, the California relay service handled 87 511 calls, in January 1988, 200 718 calls were relayed, and the number of operators were increased from the expected 60 to 120 persons (Shapiro, 1989). It is worth noting that all of the first three state-wide services were a result of state legislative action, indicating that this sort of major intervention, as relay services represent, must come through legislative action.

With regard to relay services, the USA is still not one country. More than 300 relay services are geographically scattered with different names and telephone numbers (Baquis, 1989). In 1989, 24 states had either established state wide relay services or were in the process of legislation (Taylor, 1989). In 1991, there were 31 states with such relay services and 11 states are planning such services (Currie, 1991).

In addition to relay services, a number of commercial services appeared, some of them very soon after the text telephone had arrived. In some shopping centres, TTY shopping was possible, but it did not work well, and mistakes in the orders were common. The National Railroad was also quick to establish a TTY service. It is notable that this service is not yet available in Europe in 1991, without the help of a relay service. Interestingly, a number of news centres for deaf people appeared, that is, TTY users could dial a special number and get a news print. These services preceded later teletext on television as well as today's visions of future newspaper distribution. Additionally, a TTY radio news service was initiated in Philadelphia, where the recipients had a small radio tuner, and the audio signal triggered the TTY which printed out the message (Bellefleur and Bellefleur, 1979).

2 Development in Europe

While the development in the USA is reasonably well documented, there is a scarcity of available information about the development in Europe. Several countries that have text telephones are not mentioned in this review due to lack of information. The introduction of equipment and services has been almost as piecemeal as in the USA, with the exception that services were usually nation-wide when initiated. There are still, however, many countries without text telephones, and most European countries do not have a relay service (cf. chapter 22).

The first text telephones to be used in Europe were personal imports from the USA, bought during travels abroad. However, the distribution was rather small, and there is no record of any large number of deaf people being interconnected with TDDs (Abbink and de Graaf, 1985).

The first country to manufacture and sell text telephones seem to be Germany in 1976. This happened without any participation from government; the "Deutsche Schreibtelefon", which used the EDT standard (European Deaf Telephone) was also sold in Austria, and, to some extent, in Switzerland.

Text telephones appeared early also in the UK, although there was never developed a text communication device with deaf and speech impaired people in mind. The British videotex system, Prestel, which was introduced in 1978, allowed direct communication between individual users, and thus this was used for text communication by deaf people. In 1986, a text communication device intended for document transfer in offices based on V21 was adopted as text telephone by deaf and speech impaired people. This system is currently the most widely used, but there is still a considerable degree of incompatibility. The incompatibility has even increased in 1990 and 1991 with the marketing of American TDDs based on the Baudot standard in the UK and Ireland. Those who sold Baudot-based text telephones obviously disregarded the fact that text telephones of more modern standards had already been on the market for several years, and one may assume that not many people would have bought this equipment if they had known of the incompatibility and that the relay service in the UK would not accept the Baudot standard.

Around 1980, several countries started to manufacture text telephones. Sweden began production of Diatext 1, which was based on V21, in 1979, and this text telephone was adopted also in Finland and Norway shortly thereafter.

In France, several "tlphone par crir" was commercially available in 1981; the most known is Portatel. However, in 1982 the videotex system "Minitel" was introduced, and in the following years, the French Telecom gave away four million terminals as electronic telephone directories. In 1986, Minitel Dialogue was introduced to the benefit of deaf and speech impaired people. This model allowed direct communication between two Minitel users if one of them used the Dialogue, and Minitel has to a large extent replaced other text telephone devices (Besson, 1990; Xech and Rimbault, 1987). The large number of terminals given away for free, and the low charges of renting has made text communication widely available in France, which is also reflected in the reduction of relay service use.

In the Netherlands, a trial with four text telephones was initiated in 1981 which was followed by other small-scale trials until, in 1984, a commercial model based on DTMF was presented on the market (Abbink and de Graaf, 1985).

Denmark performed some experimental trials with text telephones in 1979, but they did not appear on the market until 1986, mainly because of funding problems. The Danish text telephone was based on the Commodore +4, for which, due to failing sales, the Danish Telecommunication Administrations got an extremely advantageous offer (Dam, 1987). Somewhat surprisingly, in Denmark, the DTMF was selected instead of the V21 which was already in use in the other Nordic countries, except Iceland where the American text telephones based on the Baudot standard had been in use since 1985. Iceland is presently in the process of changing to computer-based text telephones and ASCII by adopting the Norwegian text telephone program (cf. chapter xx).

2.1 Services

With a few noticeable exceptions, relay services in Europe are still in their infancy or not even born (cf. chapter 22). The first European relay service seemed to have started in the UK, where a pilot relay services was set up by the Royal National Institute for the Deaf in London in 1980, but the further development was slow. In 1985, a regular service was launched under the name "The RNID Telephone Exchange for the Deaf" (TED). That system could, however, only cater for 170 subscribers, which, of course, was vastly inadequate to serve the total population of deaf and speech impaired people in the UK. Deaf and speech impaired people had to wait for more than ten years, until 1991, before a unit was set up to handle text communication nation-wide. This service is also run by The Royal National Institute of the Deaf, and is independent from all the major national operators.

The first nation-wide or state-wide relay services ever, appeared in Finland and Sweden. Finland had a trial service in 1981 that was made permanent in 1982, the same year as Sweden started its service. Norway followed in 1984.

In the Netherlands, a small pilot service, serving a few deaf people, was set up in 1984, and after 2 years, a regular service was initiated. In Denmark, the relay service started simultaneously with the introduction of the Danish text telephones, that is, in 1986.

In Switzerland, the multi-lingual situation seems to create certain problems. A relay service was first initiated in the German-speaking part of the country, in 1988, while a relay service for the French speaking part was opened in 1989.

3 Learning from History

The lesson from history is that some sort of regulative action may be necessary to ensure that disabled people get the equipment necessary to give them a more equal footing; that is, making society as accessible to them as possible. Both in Europe and America, development has been slow, and there are considerably fewer text telephones than people who need them.

The unfortunate situation in the UK, with three different and wholly incompatible standards, amply demonstrates that commercial interests may be contradictory to the interest of the consumers, and that there is a need to regulate the market in order to establish the degree of telecommunication interchange that is expected in modern society. It is hard to imagine a similar historical development, with lack of interconnections between countries, for the ordinary audio telephone.

The long and frustrating road towards state-wide and nation-wide relay services in the USA and the limited distribution of such services in Europe again demonstrates the necessity of legislative action to obtain private or public funding for a service that is a necessity for hearing and speech impaired people to obtain equal access to telecommunication. In the USA, sufficient relay services have in most cases come only after legislative action, and as Europe is moving towards increased liberalisation, similar development may be expected there.

References:

Abbink & de Graaf

Baquis, D. (1989). TDD relay services across the United States. In J.E. Harkins and B.M. Virvan (Eds.), Speech today and tomorrow: Proceedings of a conference at Gallaudet University, September 1988. Washington: Gallaudet University, pp. 25-43.

Bellefleur, K.M. & Bellefleur, P.A. (1979). Radio-TTY: a community mass media system for the deaf. The Volta Review, 81, 35-39.

Bellefleur, P.A. (1976). TTY communications: its history and future. The Volta Review, 78, 107-112.

Besson, R. (1990). Minitel for people with disabilities. Proceedings of the Second European Conference on Policy Related to Telematics and Disability, pp. 106-109.

Castle, D.L. (1981). Telecommunication and the hearing impaired. The Volta Review, 83, 275-284.

Currie, K. (1991). Personal communication.

Geoffrion, L.D. (1982). The ability of hearing-impaired students to communicate using a teletype system. The Volta Review, 84, 96-108.

House Document No. 9. (1988). Equal telecommunications access for deaf hard of hearing Virginians (TDD/Message relay programs). Richmond: Commomwealth of Virginia.

Levitt, H. (1982). The use of a pocket computer as an aid for the deaf. American Annals of the Deaf, 127, 559-563.

Middleton, T. (1983). DEAFNET - The word's getting around: local implementation of telecommunications network for deaf users. American Annals of the Deaf, 128, 613-618.

Pflaum, M.E. (1982). The California connection: Interfacing a Telecommunication for the Deaf (TDD) and an Apple computer. American Annals of the Deaf, 127, 573-584.

Shapiro, P. (1989). California relay service. In J.E. Harkins and B.M. Virvan (Eds.), Speech today and tomorrow: Proceedings of a conference at Gallaudet University, September 1988. Washington: Gallaudet University, pp. 85-88.

Taylor, P.L. (1989). Telephone relay service: rationale and overview. In J.E. Harkins and B.M. Virvan (Eds.), Speech today and tomorrow: Proceedings of a conference at Gallaudet University, September 1988. Washington: Gallaudet University, pp. 11-18.

Xech, S. & Mathon, C. (1987). Le Minitel Dialogue: un nuveau moyen de communication

distance au service des personnes atteintes de surdit svre ou profonde. Thesis, University of Paris.

|

(From the Matthew Starr Collection at SMECC)

|

(From the Matthew Starr Collection at SMECC)

|

(From the Matthew Starr Collection at SMECC)

|

|

| |

|

(From the Matthew Starr Collection at SMECC)

Matthew Starr

(From the Matthew Starr Collection at SMECC)

Sally Taylor States - "photo

shows Lester Zimet most likely promoting TTYs at a Deaf Awareness event in

Rochester.

("Deaf Expo", most likely just local)"

(From the Matthew Starr Collection at SMECC)

Sally Taylor tells us: Four people in next photo:

They were all being recognized during Deaf Awareness Week which was held

annually (or every two years), and MCHI would award one from each

category: cannot remember what they were. (I wonder if the DRN was in

publication at that time? I could check it out...but I doubt it as I

don't remember writing about it. I could be wrong.

Paul for his dedication by serving as advocate for development and

creation of the statewide TDD Relay Service (I just sent you a separate

photo of the award from my Iphone); Patti Lago-Avery, most likely for

her advocacy for deaf/vision-impaired people like herself; Maxine

Childress-Brown (a CODA) who was former Rochester City Council member

who advocated for the deaf people of Rochester in various ways

(wonderful woman!!!); and Alan Hurwitz (now Gallaudet U. President) most

likely for serving as president of the Empire State Association of the

Deaf (NY State) or his advocacy for closed captioning on local CBS news

(you got pictures I sent of the rally downtown to push CBS to caption

their TV programs). If you google Maxine, you'll find she just published

her memoirs which I haven't seen...last year. There is a TV program

showing her being interviewed, but alas no captions on this one I found.

Wonder if she mentioned her deaf parents, etc. etc.

(From the Matthew Starr Collection at SMECC)

HI-LINE/TEL-MED POLICY MANUAL

JOB DESCRIPTION

OPERATOR

Qualifications:

High School graduate; accurate typing skills (40-50 wpm);

ability to work with people.

Responsibilities:

1) Relay telephone calls between hearing and hearing impaired people.

2) Maintain strictest confidentiality of all calls.

3) Answer calls and provide taped information on the Tel-Med System for both

hearing and hearing impaired people.

4) Answer TTY calls for the H.A. Programs on extension 30 and transfer calls

or take messages. (as a back-up to the H.A. Administrative Clerk)

5) Record all calls (Hi-Line, Tel-Med) on the appropriate logs.

6) Fill all scheduled shifts. Obtain sUbstitutes as needed. Notify the

Shift Supervisor and/or Hi-Line Supervisor well in advance if unable to

locate a substitute.

7) Take appointments for Ear and Eye Screenings from hearing/hearing impaired

people as a back-up to the MCAHI secretary. (seasonal)

8) Monitor performance of each C-Phone, as necessary, on a log. (functional

problems, etc.)

9) Attend training and staff meetings as necessary.

10) All operators are responsible to and under the direct supervision of the

Shift Supervisor.

- 2 -

JOB DESCRIPTION

.~ SHIFT SUPERVISOR

Qualifications: High School graduate; accurate typing skills (40-50 wpm);

previous supervisory experience desired, but not necessary;

ability to work with people.

Responsibilities:

1) Perform all duties as listed for the Hi-Line Operator.

2) Evaluate operators on a day-to-day basis and report any problems to the

Hi-Line Supervisor, when necessary.

J) Assist Hi-Line Supervisor in operator performance evaluations to take

place three months after initial hiring and to continue once every six

months thereafter.

4) Document all instances of operator tardiness or disciplinary problems

on the proper forms and refer to the Hi-Line Supervisor.

5) Handle consumer problems/complaints (hearing or hearing impaired) as

they arise and refer to the Hi-Line Supervisor~ if necessary.

6) Inform Hi-Line Supervisor immediately in the case of major equipment

failure/malfunction.

7) Opening/Closing/Cleaning of the Tel-Med System. (Including proper log

ging of daily/overnight calls.)

8) Opening/Closing of the Hi-Line Service.

9) Acquire knowledge of the H.A. Alarm System and be responsible for

openings/closings of the Annex, as needed.

10) Attend training and staff meetings, as necessary.

11) All Shift Supervisors are responsible to and under the direct supervision

of the Hi-Line Supervisor.

- 3 -

JOB DESCRIPTION

HI-LINE SUPERVISOR

Qualifications: Post secondary school education; supervisory experience;

good organizational abilities; accurate typing skills

(45-50 wpm); ability to work with people; sign language

skills helpful.

Responsibilities:

1) Supervise and direct the Shift Supervisors.

2) Participate in Hi-Line operator interviews and be responsible for their

training and scheduling.

3) Fill in as Hi-Line operator as needed.

4) Conduct performance evaluations on Hi-Line operators (assisted by the

Shift Supervisors) and Shift Supervisors to take place three months

after initial hiring and to continue once every six months thereafter.

5) Report repeated instances of tardiness or disciplinary problems to the

~ H.A. Personnel Director.

6) Handle consumer problems/complaints (hearing or hearing impaired) as

they arise and refer to the Program Director, if necessary.

7) Be aware of any equipment malfunctions and arrange for repairs as needed.

8) Train Shift Supervisors on the H.A. Alarm System.

9) Tabulate and prepare statistics from Hi-Line and Tel-Med calls.

10) Arrange meetings and training sessions.

11) Attend meetings as scheduled (Hi-Line operator staff and Shift Super

visor staff).

12) The Hi-Line Supervisor is responsible to and under the direct super

vision of the Program Director.

- 4 -

HOW TO OPERATE THE TELEPHONES

1) Position the headset firmly on your head, making sure that the mouth piece

is directly in front of your mouth and that the earplug fits properly in

your ear.

2) When the phone rings, switch the incoming phone button to the "ON" position.

Also, switch the two middle buttons to the Headset position (UP). Answer

by saying "Good Morning/Afternoon/Evening Hi-Line. Mary here." or "Hi-Line.

Mary here. May I help you?"

I

3) If there is no response, assume the caller is hearing impaired and switch

the· two middle buttons to the Handset position (DOWN). Type "Hi-Line.

Mary here. May I help you? GA" or "Good Morning/Afternoon/Evening. Hi

Line. JOIm here. GA"

4) If the caller is a hearing person, leave the two middle buttons in the

Headset position. (Up)

5) When calling a hearing person, switch the outgoing phone button to the

"ON" position (you will hear the dial tone) and dial the number.

6) When calling a hearing impaired person, switch the outgoing phone button

to the "ON" position (you will not hear the dial tone) and dial the num

ber. You will be able to tell if their phone is ringing or if it is busy

by watching the red light on the C-Phone. If it flashes quickly, the

phone is busy. If it flashes slowly, the phone is ringing.

7) To disconnect callers, switch the phone (incoming/outgoing) button to the

"OFF" position.

S) The Voice button between the two phone dials can be used to prevent the

hearing person from hearing your voice. When it is in the "ON" position,

the caller will be able to hear you. When it is in the ."OFF" position,

the caller will not be able to hear you, but you will be able to hear them.

This button should only be used as a 'courtesy to the hearing party. For

example: if you have to cough, sneeze, etc.

- 5 -

HOW TO OPERATE THE C-PHONE (TTY)

The Keyboard

The C-Phone's keyboard resembles a typewriter's keyboard. You do not have to

shift keys, except for most punctuation marks.

Making a Call

1) Turn on the C-Phone using the red ON-OFF switch on its top. Almost immedi

ately you should see the cursor (a small, white, rectangular spot of light)

on the lower left corner of the screen.

2) The telephone handset should already be positioned in the rubber cups at

the top of your C-Phone. Be certain that the cord end of the handset is

in the cup marked CORD (the cup that is opposite the red ON-OFF switch).

3) To call a TTY user: Switch the outgoing phone button on the telephone to

the "ON" position and dial the number. Press the return key on the C

Phone to release the cursor. (This step is not always necessary for every

C-Phone or TTY/TDD you use, but there are some models that require this

step.) Once the party has answered you may begin to type your message.

The C-Phone will automatically return at the end of each line. The re

turn key can be used at any time to control the appearance of your message.

When an error is made in typing, simply type the letter "X" a few times

and then continue with the correction. (ie: JOHN IS CALLIGNXXX CALLING ... )

Finishing a Call

When your conversation is over, type "SK" and wait for the other party to re

spond with "SK" as well, to signal the end of the conversation. Switch the

outgoing phone button to the "OFF" position. Hold the CLEAR key on the C-Phone

down for a few seconds to clear the message from the machine.

- 6 -

CONFIDENTIALITY

Confidentiality means that the trust and confidence callers have placed in us

is respected by never revealing the identity or concerns of persons calling

Hi-Line to those outside of Hi-Line, except in life-threatening instances,

ie: suicide.

Each operator signs a pledge of confidentiality as an indication of their

awareness and acceptance of the high ethical standards vital to the work of

Hi-Line. (see figure 1)

Never give out the TTY/TDD user's phone number. If anyone wants the phone

number of a hearing impaired person, you can call that person and ask their

permission to give out their number. Clear the C-Phone after each call is

finished. (If a paper print out is used, rip up the message.)

CODE OF ETHICS FOR OPERATORS

The Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc. has set forth principles of

ethical behavior to protect and guide the interpreter and the consumer (both

hearing and hearing impaired), as well as to insure for all, the right to

communicate.

Although Hi-Line operators are not considered interpreters, we have set up

a Code of Ethics for operators, patterned after the guidelines which were

set up for interpreters.

1) The operator shall guard a LL confidences entrusted to them.

2) The operator shall render faithful interpretations, always conveying con

tent and intent of the speaker.

J) The operator shall NOT counsel, advise, or interject personal opinion

while functioning in the role of the operator.

5 )

The operator shall refrain from interpreting when family, close, personal,

or professional relationships may effect impartiality.

An operator shall use the language mode most readily understood by per

sons for which they are interpreting.

- 7 -

TTY TERMS/ABBREVIATIONS

GA: "go ahead"

GA or SK (GA to SK):

used at the end of a thought when the other person's re

sponse is wanted.

This is used at the end of the entire conversation. It

means that person is entirely finished and is hanging up.

Both mean basically the same thing. The person is say

ing, "I'm finished with what I have to say and am signing

off unless you have something to add." In other words,

"go ahead or sign off".

SK: "stop keying"

TTY: Teletypewriter

TDD: Telecommunication Device for the Deaf

PLS: Please

HD: Hold

TNX: Thanks

ASM: As soon as possible

CUL: See you later

ore. Dh, Lsee

1LY: I love you ANSWERING/RELAYING CALLS

1) Always answer the phone using voice first. Say, "Good Morning/Afternoon/

Evening Hi-Line. Mary here. May I help you?" If no one answers, assume

the caller is hearing impaired and switch the middle two buttons on the

telephone to the handset position.

2) Type "Hi-Line. Mary here. May I help you? GAt!. Always identify your

self and Hi-Line when answering both the phone and the TTY. The caller

has the right to know which operator will be assisting with his/her call.

3) After receiving the information from the caller, (their name, the name of

the person or place they are calling, the phone number) tyPe or ~a~_"PLS

HD" (please hold) or some phrase that indicates that you have recei ve-d

their message and are carrying out the request.

After dialing the number, either type "R" every time the phone rings for

the TTY caller so that he/she is aware of how many times the phone rings,

or if the caller is hearing, tell them_that the~phone is ringing .

. 5r-i) l U

- 8 -

5) After getting the party on the line, identify yourself as "The Hi-Line

Relay Service for the Hearing Impaired" and say, "I have a call for (who

ever), please hold". Sometimes, especially when calling a business that

has never received a call via Hi-Line, you may have to briefly explain how

the service operates. It is important to say "relay service" and not

"answering or interpreting service". We do not take messages or interpret,

we just relay messages. Also, use the term "hearing impaired". This term

covers both hard of hearing and deaf people.

6) After you have identified yourself to the callee, tell the caller that you

have their party on the line and that they may go ahead with their message.

7) The hearing person wanting to make a call should have the TTY number, but

sometimes it has not been given to them. In this case, first check the

Rolodex to see if the party is listed and if they are not listed there,

check the small, blue TTY/TDD Directory. If the TTY number is not listed

in the Directory, check the large, blue TDI Directory as a last resort.

If unable to find a TTY number, tell the caller that you cannot complete

their call. You should never give out a TTY number if the hearing per

son does not have it already. It is their option to ask the hearing im

paired party for the number to use for future calls.

When making a call to a hearing impaired person, allow the phone to ring

10-15 times in order to give the person time to answer the phone. Since

8)

the hearing impaired person depends on a flashing light, rather than a

ring, to let him know when the phone is ringing, time must be allowed for

the person to see the light and reach the phone.

9) When calling a hearing impaired person, be aware that a hearing person

might answer the phone. When this happens, you must pick up the telephone

receiver (handset) in order to talk to the hearing person.

10) When the hearing impaired person answers the TTY, type, "This is Mary at

Hi-Line. I have a call for (whoever) GA". After the hearing impaired

person has informed you that either they are the party you are seeking or

they will call the person to the TTY, etc., inform the hearing caller of

the response and proceed to relay the call.

11) Relay the message reading exactly what the hearing impaired person has

typed and typing exactly what the hearing person says. If the hearing per

son tells you that they will explain it to you first and then you can put

the message into your own words, explain to them that you are not allowed

to do that. They must speak as if they were talking directly to the hear

impaired person. I f the hearing person says something similar to: "Don r t

type this, but between you and I ... ", interrupt them and inform them that

- 9 -

you are obligated to type everything they say, exactly as they say it.

12) If you are unable to relay a call, because of moral convictions, ie: abor

tion, swearing, etc., you may transfer the call to another operator.

Don't hang up!

13) Do not give your opinion, advice, or suggestions even if the party asks

for your ideas. Do not launch a personal conversation, or say, "Oh, I

just had them on the line ... ". You are only relaying the message, nothing

more.

14) BE PATIENT! You may have to repeat a message again and again or the

caller/callee may put you on hold frequently. If you have to repeat a

message to either party because it is not understood, you may suggest to

the person who is speaking that they substitute different words for

clarity.

15) Relay all information to the TTY user, ie: "the line is busy", "we are

on hold", "there is a recorded message stating ... ", etc.

16) If you are unable to decipher a person's message on the TTY, tell them

you are having trouble reading them and ask them to repeat. If you still

are unable to read them, politely ask them to hold while you change TTYs.

You may then switch to the emergency TTY, designated for this purpose.

If you are still unable to read them, ask them to hang up and call back

(in order to be assisted by a different operator on a different TTY).

If you are only having trouble reading the numbers, ask them to repeat

the number and if that doesn't help, ask them to spell out the numbers,

ie: one, two, three, etc. instead of 1, 2, ], etc.

17) If you are having a problem with your C-Phone (ie: you cannot read the

message at all, nothing shows up on the screen, they can't read you, etc.)

and are unable to complete a call, record the problem on the sheet posted

on the bulletin board for this purpose. (see figure 2)

18) Only one call is to be placed per person at a time. If the number is busy

or if there is no answer, then one more call is allowed. If a caller

asks you to dial a busy number a second time this counts as their second

call. They have to call back if they wish to make another call. In order

to be fair to the consumers of Hi-Line, it is imperative that this pro

cedure is practiced by all operators.

19) Keep both parties on the line until each of them are entirely finished

with their message. This is necessary to ensure that the correct infor

mation is given.

20) Log all calls on the correct log sheets. (regular and long distance)

- 10 -

LONG DISTANCE CALLS

1) Whether dialing direct, collect, or person-to-person, always dials flOIT for

the operator, and either charge the call to the caller's number, if dialing

direct, or tell the operator the call is collect and/or person-to-person.

The only exception to this rule is when you are dialing a toll free number.

That is the only time you may dial the IT 1-800 ... II directly.

2) There are basically three different numbers that a long distance call can

be charged to. Some NTID students charge their calls to a toll billing

number. This number usually starts with the three digits r'039IT and ends

with IT534IT. There are four digits in the middle that are different for

each student. When charging a call to a student's toll billing number,

tell the operator that you are Hi-Line and are placing a call for a student

with a toll billing number. Some people have a charge card or calling card

number which is quite lengthy and easily recognizable. It is a long series

of digits usually starting with IT534-072 ... ". Lastly, a person may charge

a call to their home telephone number (716 area code) or if it is a student

to their parents' number (usually not in the 716 area).

3) When placing a collect call, do not assume that the caller wishes it to

be person-to-person when they tell you to whom they wish to speak. Before

placing the call, ask them if they want it to be person-to-person. It is

possible that they may only be giving you a person's name so that you know

who to ask for once the call is accepted.

4) Record all information on the long distance log sheet before placing the

call. This includes toll free numbers. Also, make a note in the miscella

neous column of your personal log.

5) If a caller asks you to dial Directory Assistance for a local number, ask

them if they have called 1-800-855-1155. This is a toll free TTY number

for Directory Assistance. There is a charge for Directory Assistance

information if it is listed in the book, but no charge if it is not listed.

6) There is a charge for calls to OTB Race Information, Time and Temperature,

and Accu-Weather so if a caller wishes to call any of these numbers he/she

must give you their number to charge the call to and you must dial the

operator first. Inform the caller that sometimes the person speaking on

the tape talks very fast and it might not be possible for you to type all

the information in just one call. It might be necessary to call back a

second or third time.

- 11 -

LOG TERMS

All calls are to be logged on the log sheets. Each operator uses a new sheet

each day. (see figure J) The columns are as follows:

#: Used to show the number of calls received. (ie: 1, 2, 3, 4 ... )

TIME REC.: Record the time you answered the phone. The digital clock in

. the Hi-Line office is the official timepiece. It should be

used not only for recording the times of your calls, but also

for the changing of the shifts and opening and closing times.

Record the time the call was finished.

TIME END:

CALLER ZIP: Before placing the call, ask the caller for his/her zip code.

This information is necessary for annual reports which are

prepared for the United Way.

CALLEE ZIP: After relaying the call and before hanging up, ask the per

son you have called for their zip code. Again, this infor

mation is needed for the United Way.

M:

Check if the caller is a male.

Check if the caller is a female. (If the name given could be either

male or female (ie: Chris, Terry, etc.) make an educated guess.' Some

times a person's gender can be ascertained after relaying part of the

call. )

EMP. (EMPLOYMENT): Check if the call concerns anything having to do with

F:

employment. ie: Looking for employment, calling in sick or

late to work, etc.

A. E. T. (ADULT EDUCATION TRAINING): Check if the caller is inquiring

about Continuing Education courses, etc.

PROF. (PROFESSIONAL): Calls to doctors, la¥zyers, dentists, vets, Social

Security office, etc.

BUS. (BUSINESS): Calls to department stores, babysitters, newspapers,

plumbers, electricians, landlords, cable companys, etc.

SOC. (SOCIAL): Any type of social related call. ie: calls to relatives,

friends, etc.

EMER. (EMERGENCY): Some doctor calls, ambulance, police, fire department,

etc.

INT. (INTERPRETER SERVICE): Check if they are calling trying to locate

an interpreter.

H-HI (HEARING TO HEARING IMPAIRED): If a person is calling to a hearing

impaired person, check here. (You should also check the type,

of call being made.)

- 12 -

L.D. (LONG DISTANCE): Check here if you are placing a long distance call.

You should also record the proper information on the long dis

tance log sheet.

STUD. (STUDENT): If the caller is a student at NTID, RIT, or MCC check

here. (This information can usually be determined when a call

er mentions that he/she is a student or when he/she gives a

toll billing number when making a long distance call.)

S.S. (SOCIAL SECURITY): When a caller is phoning the Social Security office

to discuss either their SSI or SSD, check here.

# CALLS OUT: Usually you will record Ill" here. The policy at Hi-Line is

that we are allowed to place one call per person at a time.

(see rule #18 under Answering/Relaying Calls)

MISCELLANEOUS: This is where a note should be made if there is a busy

signal (BUSY) or no answer (NA). This column can also be used

for any other pertinent information, ie: the C-Phone acted up,

a wrong number was given, etc.

LONG DISTANCE LOG

There is one long distance log for all operators to share each day. (see figure

4) On this log you should record the full name of the person placing the call,

the full name of the person they are calling to and their phone number. Check

under the appropriate column whether the call is direct or collect. Also note

person-to-person calls by writing IIP_PIl. Finally, record the number the call

is being billed to. All this information should be recorded on the log before

dialing the number.

At the end of your shift, your personal log should be placed on the Hi-Line

Supervisor's desk. The Shift Supervisor on duty for the last shift of the day

shall be responsible for putting the long distance log in it's proper place.

(on the Supervisor's desk)

r----.,

- 13 -

OPENING/CLOSING PROCEDURES (HI-LINE)

Shift Supervisors are responsible for learning the H.A. Alarm System and for

opening/closing Hi-Line and/or the Annex building. When a Shift Supervisor

is not on duty, an operator who has a key to the building should be respon

sible.

OPENING

To open the Hi-Line area, the key must be obtained from the desk in the Hi-Line

Supervisor's office. The major responsibility of opening Hi-Line is to make

sure that the answering machine is turned off. The procedure is as follows:

1) Record the number of overnight calls from the machine on the sheet

posted near the machine. (see figure 5)

2) Flip the lever on the front of the machine to STOP. (Make sure that the

tape is not playing when you do this.)

J) Flip the white button on the back of the machine to "OFF". This action

will turn off the machine completely.

4) Unplug the machine from the phone jack (under the table) and plug in the

first incoming phone line.

CLOSING

To close, follow the reverse procedure:

1) Unplug the first incoming phone line from the jack and plug in the machine.

2) Flip the white button on the back of the machine to "ON".

J) Flip the lever on the front of the machine to PLAY.

When closing Hi-Line, the Shift Supervisor should also be sure that all C-Phones

are turned off and that the work area is straightened up. Log sheets for the

morning shift should be placed on top of the C-Phones. Also, the coffee machine

should be turned off. This is very important to remember as it could cause a

fire or burn the coffee pots if left on. All windows in the meeting room should

be shut also. If a maintenance man is on duty, he will usually check all of

these items, but it is helpful to double check. Finally, the door to the Hi

Line office should be shut and locked and all lights should be turned off be

for setting. the alarm and leaving the building.

- 14 -

HOW TO OPERATE TEL-MED

Hi-Line Operators/Shift Supervisors are responsible for answering and record

ing Tel-Med calls. When Tel-Med rings, the operator who is not on a call should

answer. (If all operators are on calls, the first operator who is not on a

long distance call and has the opportunity to place their parties on hold should

do so and answer Tel-Med.) Answer by pressing the flashing white button. Say,

"Tel-Med Information Service. May I have your request, please/May I help you?"

After the caller has given their choice, ask them for their zip code (needed

for United Way annual reports) and record it on the Tel-Med log. (see figure

6) Then say, "one moment, please" and press the red hold button. Select the

proper tape from the rack and slide it into the slot. Then record the time of

the call and the number of the tape on the log. If the caller is a female, just

record the tape number. If the caller is a male, record the tape number and "M"

after it. If the caller is a child, record a "e" after the number. Be sure

you record the information in the correct column for that date. If you need to

reach a caller after you have put them on hold, press the white button again.

If you need to disconnect a caller, press the yellow disconnect button.

Often a caller might request information concerning their Blue Cross/Blue Shield

or Medicare policies. In this case, refer the caller to the correct number

which is listed on the front of the machine. After doing this, place a tally

mark in the upper left hand corner of the log next to the service to which you

referred the caller.

If a caller requests a topic which we do not have, make a note of that topic on

a list near the Tel-Med records.

If a caller requests a brochure, record their name and address on the sheet

provided.

- 15 -

OPENING/CLOSING PROCEDURES (TEL-MED)

The Shift Supervisor on duty is responsible for opening/closing Tel-Med. If

there is no Shift Supervisor on duty, one of the operators should follow the

procedures listed below. Also~ if the Shift Supervisor is preoccupied, he/

she may delegate the responsibility to one of the operators.

OPENING

Tel-Med should be opened at 9 a .m. on Monday - Saturday and 10 a .m. on Sun

days. The numbers on the iwo tape counters at the bottom of the machine should

be added together and recorded on the Overnight Record. (see figure 7) The

overnight tapes should be removed from the machine and the silver switches

should be switched off (to the down position).

CLOSING

About 5-10 minutes before closing time (Monday - Friday: 9 p.m.; Saturday: 5

p.m.; Sunday: 2 p.m.) the machine should be cleaned. The metal head of each

slot should be cleaned, as well as the metal bar running up and down each side.

Do this by using the Q-tip swabs and the liquid head cleaner. This procedure

should be followed every day. Once a week, on Wednesday nights, the rubber

rollers should be cleaned.

After cleaning the machine, the overnight tapes should be inserted and the sil

ver switches should be switched on (to the up position). The tape counters

at the bottom of the machine should be returned to zero.

The calls for that day should then be added up at the bottom of the column.

Add up the female callers first, then the male callers, and finally the

children. For example, if there were a total of 20 calls with 9 females,

8 males, and J children, the total at the bottom of the column would look

like this: 9 + 8 + J = 20. The same figures should then be recorded o~ the

Monthly Call Distribution Sheet. (see figure 8)

- 16 -

JOB COURTESY

1) BE ON TIME! It is inconvenient for other operators if you are late be

cause they have to do your work. Also, Hi-Line users depend on us to

be available at specific hours. Repeated tardiness will be grounds for

discharge. The Shift Supervisor will record any instances of tardiness on

the proper form. (see figure 9)

2) No visitors are allowed in the Hi-Line area.

3) No personal calls should be made from the Hi-Line phones. If it is abso

lutely necessary to make a personal call, use the Health Association

phone (extensions 30, 45 - located in the Hi-Line Supervisor1s office, or

46 - located in the small office adjacent to the large meeting room). Per

sonal calls should only be made on breaks. No personal calls should be

coming in on the Hi-Line phones at all. No personal calls should be re

ceived on the Tel-Med lines, except for in an emergency.

4) Be responsible for your own work area. After each shift ashtrays should

be emptied, coffee cups washed or disposed of, magazines returned to the

book shelf, and scratch paper should be disposed of. The last shift is

responsible for turning off the coffee machine.

5) No foul language or party atmosphere.

6) Many callers are frustrating, but please do not make comments about them

aloud. This can be heard by people in the meeting rooms, people walking

by the office, and people on other calls.

7) Do not eat over the TTY. Food drops into them and we have to send them

to Missouri to be repaired. Also, personal grooming should be done at

home or in the restrooms. Therefore, there will be no combing of hair,

applying make-up, fingernail polish, etc. in the Hi-Line office.

8) Do not talk to other operators while in the middle of a call or if they

are in the middle of a call, unless absolutely necessary.

- 17 -

LINE OF AUTHORITY

All problems/complaints (whether concerning a Hi-Line call or another operator)

should be referred to the Shift Supervisor. If the Shift Supervisor is unable

to resolve the problem then it should be referred to the Hi-Line Supervisor.

If the Hi-Line Supervisor is unable to resolve the problem, then it should be

referred to the Program Director and then on to either the Personnel Director

or the Executive Director. If the problem/complaint concerns the Shift Super

visor, then the operator should make an appointment to talk with the Hi-Line

Supervisor.

DISCIPLINARY WARNINGS

Shift Supervisors will verbally warn operators of any infraction of policy or

procedure. If immediate improvement is not shown, the Shift Supervisor will

take further action by completing the Disciplinary Warning Form and referring

it to the Hi-Line Supervisor. (see figure 10)

Among the reasons for discharge are the following:

1) Dishonesty

2) Insubordination, including refusal to do work for which qualified

3) Conveying confidential information about Hi-Line and/or it's consumers

4) Repeated absenteeism or tardiness.

PERSONNEL POLICIES

BREAKS

1) If you are working on a 3 or 4 hour shift, you should take a 15 minute

break. This should be taken at a time when it is convenient for the other

operators on your shift (certainly not while another operator is on break).

All 15 minutes should be taken atone time. You cannot split your break

into 5 minute increments. If you do not take a break on one shift, you

cannot save it for a different shift. This break is paid.

- 18 -

2) If you are working a 5 or 6 hour shift, you should take a 20 minute break.

Again, this should be taken all at once and at a time convenient for the

other workers on your shift. This break is paid.

3) If you are working a 7 hour shift, you should take either one 30 minute

break or two 15 minute breaks. Again, the same rules apply. This break

is paid.

LUNCHES /DINNERS

If you are working an 8 hour day, you are entitled to and must take either a

lunch or dinner break of one hour. This break is not paid and should not be

included on your time sheet. Along with the lunch/dinner break, you may take

your 15 minute breaks for every 3 or 4 hour period.

SUBSTITUTIONS

Workers are responsible for filling all scheduled shifts and/or finding substi

tutes as needed. When a substitute is found, both the scheduled worker and

the substitute must initial and date the change on the schedule. If this is

,~ not done, and a Substitute does not show up for the shift, the worker origin

ally scheduled for that shift will have that time deducted from their pay.

If both workers are unable to initial the change, the Shift Supervisor on duty

may initial and date the schedule for them. Shift Supervisors will be given

copies of the weekly schedule and if workers are having difficulties finding

subs they may contact the Shift Supervisor for advice. If unable to find a

substitute, the worker is still responsible for the hours and must work. If

a worker does not show up for his/her shift, a Disciplinary Warning Form will

be completed by the Shift Supervisor.

ILLNESS

If you experience a sudden illness, and there is not sufficient time to ob

tain a substitute, or if the nature of your illness prevents you from locating

a sub, you must inform the Shift Supervisor at least one hour (if not sooner)

prior to the start of your scheduled shift. If the Shift Supervisor is un

available, the Hi-Line Supervisor should be notified.

- 19 -

PAYROLL AUTHORIZATION FORM

All staff are responsible for filling out their own payroll authorization form.

(see figure 11) Staff are paid twice a month, on the 15th and the last day of

the month. If either of these days falls on a weekend, then checks will be

handed out on the preceding Friday. The forms should be completed in the

following manner:

Pay Period: Either from the first of the month through the 15th (ie:

1/1 - 1/15) or from the 16th through the last day of the month

(ie: 1/16 - l/Jl).

Name & Address: Please fill in your complete name and address.

Program: Should read "Hi-Line".

Position: Should read either "Operator" or "Shift Supervisor".

Dept. #: Disregard

The number of hours worked should be filled in under the correct date and then

the form should be signed and given to the Hi-Line Supervisor who will verify

the number of hours worked before handing it in to the business office.

The dates that the form is due are posted on the Hi-Line bulletin board. The

form should be given to the Hi-Line Supervisor no later than 9:00 a.m. on the

morning it is due. If a staff member neglects to hand in his/her form, he/she

will not receive a check for the pay period and will have to wait until the

next pay period to submit his/her hours.

The Hi-Line Supervisor will also keep a record of total number of hours worked

for the year. No part time employee is allowed to work more than 1,000 hours

in one year.

SUGGESTION BLANKS

The Health Association provides a Suggestion Blank which can be filled cut and

returned to the Personnel Director. (see figure 12) This blank should only

be completed by Hi-Line Operators/Shift Supervisors when they have an idea that

will benefit the H.A. as a whole.

Hi-Line also has a Suggestion Blank. (see~flgure 13) This is to be filled out

and returned to the Hi-Line Supervisor wheri there is an idea that pertains only

to Hi-LinQ_

20 -

CONFIDENTIALITY PLEDGE

I, the undersigned Hi-Line worker, understand the personal and confidential

nature of this service. Therefore, I promise that:

(1) Under no circumstances, except in life threatening emergencies,

ie: suicide, will I disclose to any individual not connected

with Hi-Line the identity of any caller or information about any

caller without his or her expressed permission.

(2) I will share (upon request) any problems or difficulties I may have

with my work only with persons associated with Hi-Line who have a

consulting and supervisory function over my work.

(3) I will never give out information concern-ng other workers, ie:

their full names, home addresses, and telephone numbers.

(4) In the event of my withdrawal or resignation, I will continue to

hold in strictest confidence all personal and confidential infor

mation related to the work of this agency.

NAME

DATE

----------------------------~

|

|

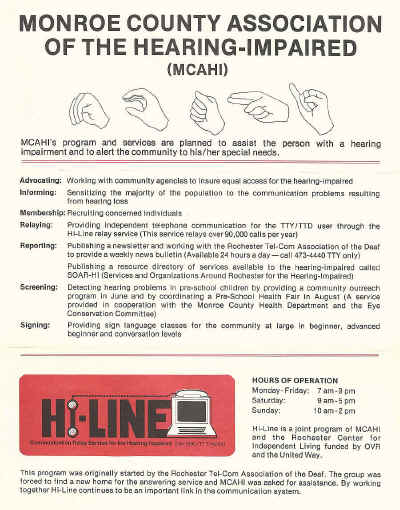

HI-LINE Communication Relay Service -

From RTCAD TTY/TDD Directory 1987 page 65 - From the Paul and Sally Taylor

Collection at SMECC

MCAHI

Monroe

County Association For the Hearing Impaired

A

program of the Health Association

MCAHI's

program and services are planned to assist the person with a

hearing impairment

and to alert the community to his/her special needs.

*

Advocacy

*

Information and referral

*

SOAR-HI Directory

*

HCAHI Newsletter

*

Hi-Line TDD Relay Service

*

Sign Language classes

*

Ear/Eye Screening

* And many more!

For

more information, call:

JacqueliI'.e

Schertz, Program Director MCAHI

973

East Avenue

Rochester, New York 14607

(716)

271-3540 V/TDD

(716)

271-8800 TDD Answering Machine

From RTCAD TTY/TDD Directory 1987 - From

the Paul and Sally Taylor Collection at SMECC |

|

|

From RTCAD TTY/TDD Directory 1987 page

66 - From the Paul

and Sally Taylor Collection at SMECC

MINI-LINE

- Private Relay Service for

the Deaf and

Hearing Impaired - for

more information call: 586·3032 or write: Sue

Taylor 154 Penhurst Rd. Rochester,

N.Y. 14610

|

|

| Accessibility

for all |

| Relay

services for deaf people - reprinted from ITU

News - June 2011 |

|

| photo credit: |

Christopher Jones,

co-Convener of the Joint Coordination Activity

on Accessibility and Human Factors (JCA-AHF) |

|

|

| Photo

credit: Ultratec |

Based on a contribution by Christopher Jones,

co-Convener of the Joint Coordination Activity on

Accessibility and Human Factors (JCA-AHF)

How do you make a phone call if you are deaf? Or,

more to the point, how do you respond to a call? Do

you have to ask your child or your neighbour to make

appointments for you or provide personal details to a

caller? Do you have to run out into the street looking

for someone to call an emergency service? These are

just some of the scenarios that a hearing person takes

for granted will not happen.

There are many different types of deafness:

profoundly deaf people who use only sign language;

profoundly deaf people who have intelligible speech;

profoundly deaf people who have less intelligible

speech; hearing people who are deafened; people who

are blind as well as deaf; and people who are hard of

hearing. People with age-related disabilities may fall

into any of these categories.

Many deaf people have problems in daily living by

not being able to make telephone calls to hearing

people or organizations without someone or something

in place to assist them. This is why relay services

are so important for deaf telecommunication. They are

professional services that do not rely on the kindness

of friends, family or strangers.

But while relay services have been around for more

than 40 years, most countries still do not offer these

services for deaf people, even though hearing

impairment is reportedly the most frequent sensory

deficit in human populations, affecting an estimated

250 million people in the world.

Today, being able to make contact by telephone is a

prerequisite for effective participation in society.

And the United Nations Convention on the Rights of

Persons with Disabilities provides for Full and

effective participation and inclusion in society.

From teleprinters to videophones and more

In the 1960s, deaf people started using

teleprinters (teletypewriters, also known as TTY) with

custom made acoustically coupled modems to communicate

with each other over the telephone network. The modems

used the ordinary telephone handset as the

transmitting device, thus enabling text to be sent

over the telephone network, character by character.

This was in real time and was the first real-time text

later standardized at ITU as part of Total

Conversation and used in the first accessibility

standard (ITUT V.18) for text phones.

Teletypewriters led to the development of text

telephones, which incorporated the printing device and

the modem in one portable unit.

When deaf people need to communicate with hearing

people who do not have text telephones, there is a

problem. Based on the work of the early pioneers (see

article How

the deaf developed a phone of their own), who were

all deaf, the response has been to develop a relay

service.

As technology progressed and the Internet

developed, it became possible for deaf people to

communicate with each other using video. This works

for deaf people who use sign language. Many deaf

people who have sign language as their first language

find it difficult to use text phones because they

require written language. Videophones have become

increasingly popular with these deaf users. They use

them to communicate with each other, and with hearing

people who can use sign language.

What is a relay service?

| |

|

| Photo

credit: BT |

| Video

phones and text phones are among devices that

benefit from ITUs standardization work |

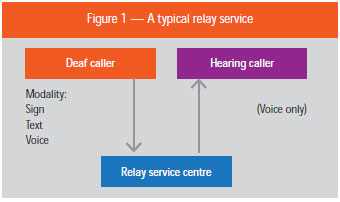

A relay service is simply a way of enabling a deaf

person using whatever modality they choose to

communicate with a hearing person, and vice versa

(Figure 1).

The modality used by the deaf caller may be text,

voice or sign. The different types of relay services

meet the different individual needs. These different

types of relay services for deaf people are: text

relay service; text relay service with voice carry

over; captioned telephone relay service; and video

relay service.

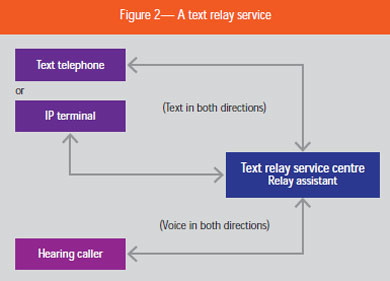

Text relay service

In a traditional text telephone relay service

(Figure 2), deaf callers use a bespoke text telephone

terminal to type the words that they want to say. A

more modern version uses the Internet, and is known as

an Internet Protocol (IP) relay service. This can be

accessed via a personal computer, laptop, personal

digital assistant or smartphone. Both use the same

operating method:

-

The deaf caller types his or her

communication to a text relay service centre,

where a relay operator will read aloud the typed

words to the hearing caller.

-

The hearing caller speaks to the

relay operator, who will transcribe the speech as

text, transmitting the typing back to the deaf

persons terminal, whether this is a text

telephone or an Internet device such as a laptop

or a smartphone.

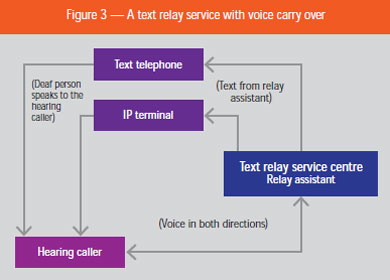

Text relay service with voice carry over

For a deaf person who has speech that can be

understood by the hearing caller, the deaf person can

use a variant of a telephone relay service known as

voice carry over (Figure 3). Instead of typing the

words, the deaf person speaks directly to the hearing

caller. The hearing caller speaks to the relay

operator, who will transcribe the words as text, which

goes back to the deaf persons display screen. The

flow is either voice or text, but not both at the same

time.

Text relay services are available in many

countries, including the United States, Canada,

Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Sweden and

Denmark.

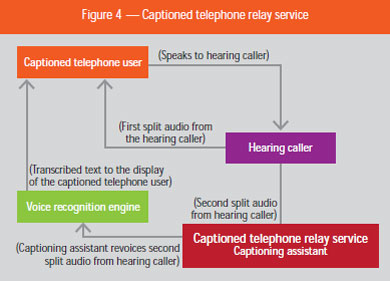

Captioned telephone relay service

A captioned telephone relay service (Figure 4) is

the most functionally equivalent and appropriate type

of relay service for people who are hard of hearing,

people who have been deafened, and deaf people whose

speech can be understood by hearing people. This is an

enhanced voice carry over system where a deaf person

has a normal telephone conversation in both directions

with the hearing caller.

The hearing persons speech path is split into

two: one path goes directly to the deaf caller, who

may understand most, some or none of the speech,

depending on their level of hearing loss or the level

of background noise. The other path goes to a

captioned telephone relay service centre, where a

captioning assistant will revoice everything the

hearing person says, word for word, into a voice

recognition engine. The transcribed text is

transmitted to the deaf users display, which could

be a laptop or a smartphone.

A captioned telephone relay service can be accessed

through the Internet using any browser device, such as

a personal computer, laptop, netbook, tablet, personal

digital assistant or smartphone.

Captioned telephone relay services are available in

the United States every hour of the day and night,

every day of the year. The cost to the user is the

same as the cost of a standard telephone call.

Australia is trialling a captioned telephone relay

service, and New Zealand has issued a tender for one.

Many people with age-related disabilities cannot

cope with computers; a bespoke captioned telephone is

what they need. This looks like a normal telephone but

with a large display to enable them to see transcribed

text from the hearing caller.

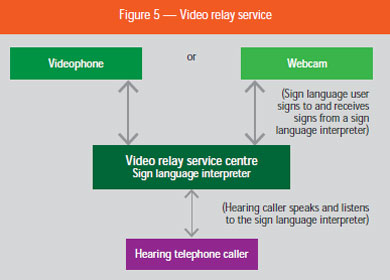

Video relay service

A video relay service (Figure 5) is used by deaf

people whose first language is sign language. Many of

these people do not have sufficient written language

skills to use text relay services. And they do not

have sufficiently intelligible speech to use a

captioned telephone relay service. They use either

videophones or a webcam on their personal computer,

laptop, tablet or smartphone (with the webcam in

front), together with videophone software or apps.

They sign their concepts to a video relay centre,

where a sign language interpreter will translate from

their sign language concepts into spoken language,

then voice over to the hearing caller. The hearing

caller speaks to the sign-language interpreter who