|

A Miniature Radio Receiver for Police

Use

by Lawrence H. Smith, Radio Technician, Police

Department, Atlantic City, N. J.

FBI LAW ENFORCEMENT BULLETIN Date? probably 40s or

50s

Article Courtesy Glendale Police Museum, Glendale Arizona

The Atlantic City Police Department now has in successful use a tiny

radio receiving set concealed in a patrolman's cap over which he receives

all calls emanating from the headquarters transmitter. The receiver weighs

less than 2 ounces. Together with the batteries, antenna, and earpiece,

the weight is 6 Ounces. Including the cap and badge, the entire ensemble

weighs 15 ounces.

By using a special lightweight cap, with an aluminum or plastic badge,

together with a few contemplated changes in the design of the receiver, we

hope to soon cut this weight by approximately 3 ounces.

The receiver is in an aluminum case, 1 'V7/8 inches square and 1 inch

thick. It is concealed in the peak of the cap behind the badge. Operation

is from hearing-aid batteries located in the brim to

give equal weight distribution. The sound is carried to the ear by a small

Telex earpiece concealed in the brim to which is connected a short piece

of sound tubing which carries the voice outside the cap and into the ear.

Volume control is obtained by adjusting the tubing closer to the ear or

farther away.

Batteries and Tubes

The "A" battery used will give continuous operation for 7

hours, the "B" battery lasts from 7 to 10 8-hour days.

Four Raytheon subminiature tubes are utilized READ

THE PAGES BELOW FOR THE REST!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Radio Personality Raises Communication in

Loudoun County

Sheriff Roger Powell Uses the Radio Equipment Donated by Arthur Godfrey.

Picture courtesy of The Winslow Williams Collection c/o The Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA

(Loudoun County Sheriff’s Office - 04/06/07)The second week of April marks National Public Safety and Telecommunicators Week. The week is dedicated to the men and women who serve as public safety call takers and dispatchers.

The way public safety dispatchers communicate with Loudoun Deputies today can be traced back 50 years ago to a gift from popular radio personality, Arthur

Godfrey.

In a letter dated November 22, 1952, Roger F. Powell, who served as Loudoun’s Sheriff from 1952 to 1959, informed then County Chairman I.W. Baker that Arthur Godfrey had donated $2000 “to be used in installing a county police radio communication system.” The revelation of Godfrey’s name was controversial at the time as the radio personality had asked for his contribution to remain anonymous. Sheriff Powell was forced to release the radio stars

name after some supervisors declared there would be no budget increase requests for the Sheriff unless the identity of the donor was revealed. “No money for an extra man until you talk,” the board demanded according to one local newspaper.

Godfrey, who started his radio career in Baltimore in 1929, later joined Washington D.C.’s NBC affiliate. In 1942 his morning show could be heard on CBS’ flagship station, WABC in New York. Back in Loudoun County, Godfrey purchased the Beacon Hill Estate west of Leesburg, Virginia and commuted by plane from his farm to studios in New York City every Sunday night. Godfrey would affectionately refer to his land as ‘the old cow pasture’ on his radio show.

In the revelation letter to the Board of Supervisors, Sheriff Powell stated that he discussed with Godfrey issues within the Sheriff’s Office and the fact that two county tragedies had recently taken place: a robbery and shooting in Hillsboro and the Fox family murders. Powell told Godfrey that he would like to have a county police system “whereby all the emergency units, such as fire departments, rescue squads, and the game warden could be tied together as more efficient operating units”. Mr. Godfrey asked, “What will it cost?”

According to the letter, initial estimates for the radio system were in the range of $1200. In response to the figure Godfrey said, “one thousand or two thousand dollars, get busy, don’t let any moss grow on it. I’ll do that much for my people of Loudoun County.” The cost rose to $1600 before Godfrey donated a total of $2000 stating “we don’t want any dead spots in the system; (get) the kind of equipment that will do the job right.” Less than a month later on December 18, 1952, a headline in the Loudoun News proclaimed “Loudoun County Police Radio Station Goes On Air Today”.

Only a few years later, Godfrey continued his good will with the donation of a small portion of his land off of Old Waterford Road near Leesburg. The land was used by the Loudoun Sheriff’s Office to build a radio tower; greatly increasing the agency’s communications capabilities. Robert W. Legard, who served as Loudoun County Sheriff from 1964 to 1979, worked with Hankey’s Radio in Frederick, MD to erect a tower on the land. The tower broadcasted two low-band channels, one for the Sheriff’s Office and one for Loudoun Fire/Rescue. The tower still stands today but is no longer in use.

For several decades, Sheriff’s Offices across the state used the low-band frequency of 39.5 megacycles, which caused problems on busy weekends. On some evenings, Fauquier County, VA deputies and Loudoun deputies would compete for airtime when responding to calls. Because of the nature of low-band frequencies, which can skip great distances off of the atmosphere on clear nights, the radios would pick up radio traffic from law enforcement as far away as Bogalusa, Louisiana.

For nearly 40 years the dispatching system broadcast from the county jail on Church Street in Leesburg. In 1990 the needs of the Sheriff’s Office dispatch center outgrew the facility and moved to its current location on Courage Court. The dispatch office, today referred to as the Emergency Communications Center (ECC), employs over 40 dispatchers. In 2006, the staff handled over 390,000 9-1-1 and non-emergency calls.

In 2000 and after years of requests, current Loudoun County Sheriff Steve Simpson secured funding for Loudoun’s public safety community to finally upgrade to an 800 MHZ digital trunking system. The 11-channel system allows separate simultaneous channels for the agency’s specialty units and covers the entire county with few drop-out areas. A few years later Sheriff’s patrol cars were outfitted with mobile data terminals allowing deputies to turn in paperless reports from the front seat of their vehicles.

Godfrey was instrumental in the implementation of the public safety radio system in Loudoun County, but his good will did not end with the Sheriff’s Office. Over the years Godfrey donated an ambulance and the financing for an entire wing for Loudoun County Hospital. In 1960 Godfrey donated $200,000 from the sale of his 'old cow pasture' for the development of an airport. The area is now known as Leesburg Executive Airport at Godfrey Field.

Arthur Godfrey passed away in New York in 1983 and is buried in Union Cemetery only a few miles from his former Leesburg home.

The Loudoun County Sheriff’s Office was founded in 1757 and is currently celebrating their 250th anniversary.

(submitted by Albert LaFrance to SMECC) |

|

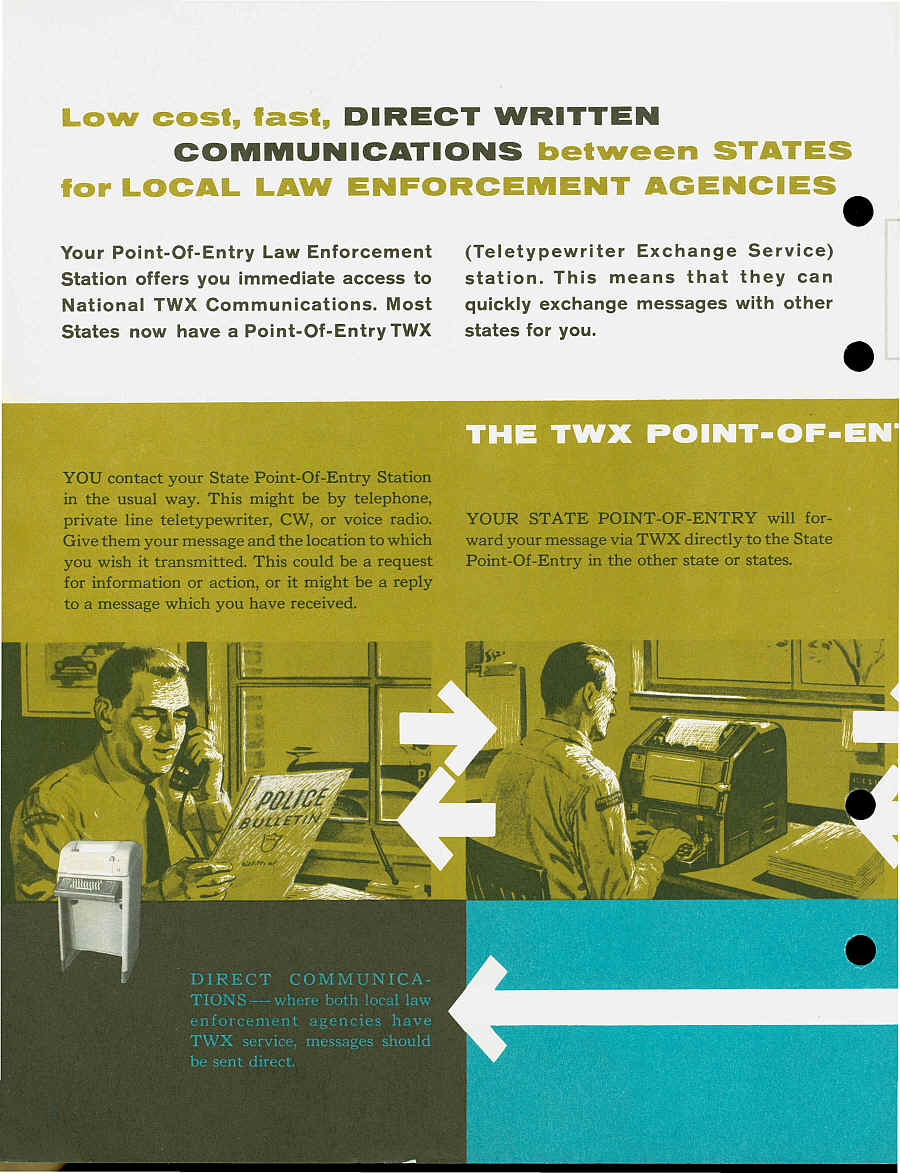

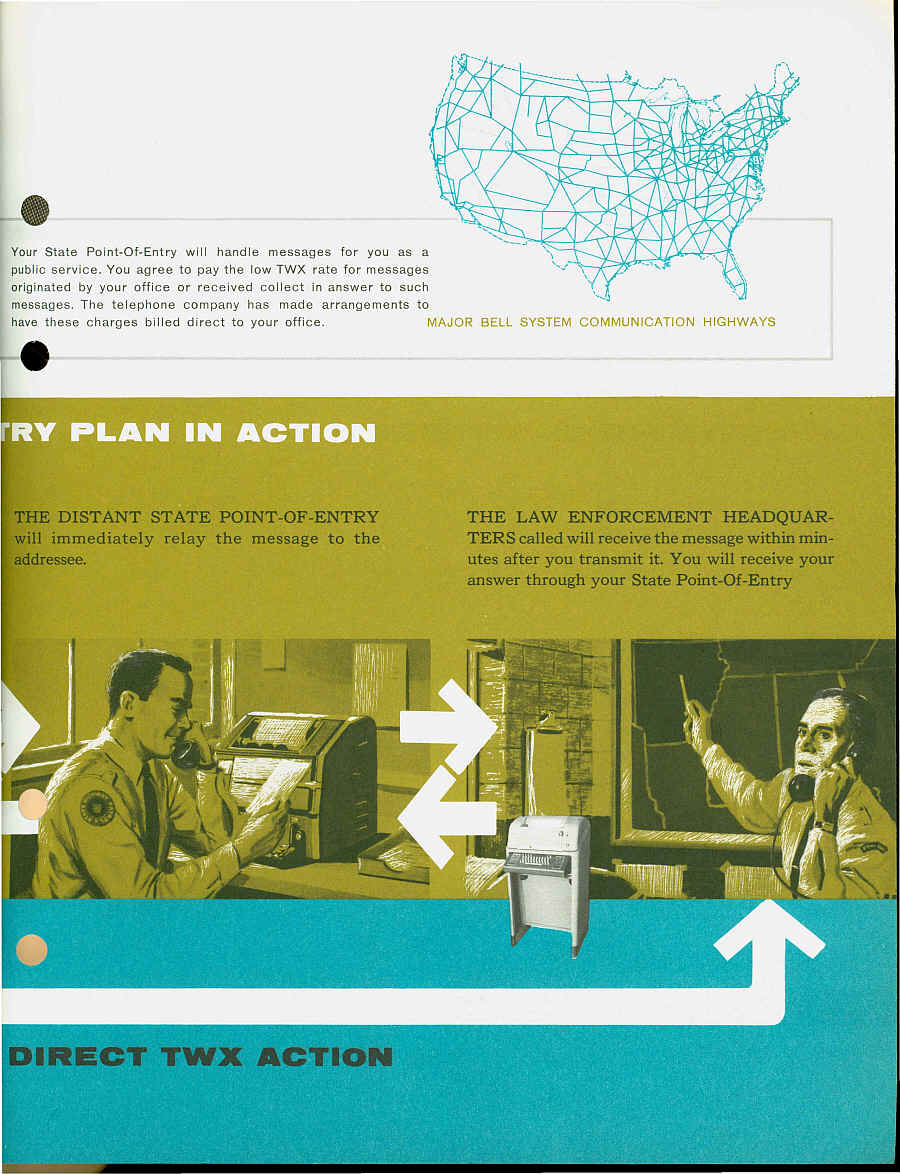

Hi Ed:

Likely you will not find much about Law Enforcement teletype in this

group, as we are primarily a military group. We specialize in military

communications.

There are some here who may have experience in law enforcement

teletype, myself included, but most do not.

However, what you are seeking in the way of Law Enforcement

Teletype comes under the heading of "NLETS" or

"LETS". NLETS

is the National Law Enforcement Teletype System, and there are

several components to it in each of teh 50 states and Canada.

There is also an INTERPOL affiliation.

NLETS is separate from NCIC - National Crime Information Center

which is run by the FBI.

In most states, NLETS is run by the states, and in many cases,

State Law Enforcement agencies oversee its' operation. These

agencies might include such as FDLE - Florida Dept of Law Enforcement,

or SLED - South Carolina Law Enforcement Division -- the organizations

who are authorized to grant Police Powers (via their various state

legislatures), to the many police departments within and under

their jurisdictions.

FWIW, there are 38,000 Police Depts in the US (PDs, SOs,

HPs, State Police, Constabularies, etc)...and each dept has at

least one NLETS terminal, with most having several. Big network!

Check out NLETS and "National Law Enforcement Teletype"

on Google, as there seems to be a fair amount of information

there of interest.

When I worked in law enforcement, the standard teletype

gear was the Model 28 ASR, some Model 32s, and later

a few model 33s, and finally computer terminals.

Every PD, SO and law enforcement agency had its' own

"Routing Indicator", including all US military Military Police

stations who were tied into NLETS. Today, NLETS is a

high speed, pretty efficient system which is often used to

pass BOLOs, RAP sheets and other police business on

suspects. BOLOs are essentially the old "APBs" and

stands for "Be On Look Out...." RAP Sheets are criminal

histories on individuals (in some cases, we had them as long as

21 pages on a single individual when I worked for the Brevard

County Sheriffs Office in Florida).

Hope this helps,

------------------------------------------------------------

While

NLETS is separate, it is firmly connected. One accesses NCIC through

normally a state connection, such as TCIC in TN, MULES in

Missouri

, etc, and then THROUGH NLETS to NCIC.

A

state/local user does not access NCIC directly, the pipe and parsing is

provided by NLETS.

The

state provides training, administration, etc to the end user agencies.

Going through TAC school was boring – until they showed us

administrative messaging. While now a days it is every day stuff, the fact

we could message back and forth to other agency TAC’s in the room, many

times cute female TAC’s was pretty cool – until the state director

came in and advised us that the control operator could see every message

in the state control center (same building where we were doing our

training).

Took

all the fun out of it.

The

first agency I was with had an ASR33 back in a hallway, but I never saw it

being used.

bbowerslists@gmail.com

-----

From:

CommCenter-1@yahoogroups.com [mailto:CommCenter-1@yahoogroups.com] On

Behalf Of NNN7DXB@aol.com

Sent: Monday, April 15,

2013 9:14 AM

To: CommCenter-1@yahoogroups.com

Subject: Re:

[CommCenter-1] need scanned material & stories for our law

enforcement...

NLETS

is separate from NCIC -

National

Crime

Information

Center

|

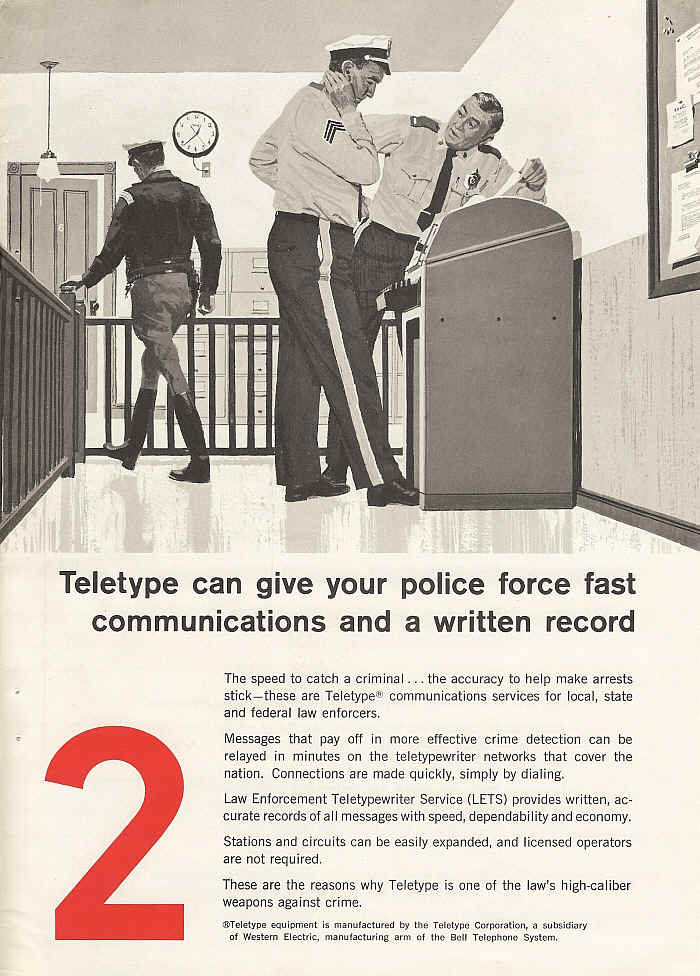

1963 Bell Public

Telephone Teletype Emergency Reporting Group Alerting ETV 6P Ad

-

| THE

GLENDALE NEWS |

|

OCTOBER

12, 1981, |

|

Teletype

Speeds Four-State Crime News To Glendale |

| A

new teletype recently installed in the Glendale Police Station, is

keeping the department alerted on crime in the four-state area of

Oregon, California, Nevada and Arizona.

Immediate

news of car thefts, escaped prisoners, bad check artists. runaways,

and wanted criminals who maybe headed toward |

Glendale,

is registered on the teletype. giving police a printed record which

may be filed for reference.

Similar

machines are located in the sheriff's office, the FBI in Phoenix,

the main Phoenix police station, the Arizona Highway Patrol office

and in Tucson, Chandler and Scottsdale. |

Effectiveness

of the teletype was illustrated by Chief of Police Allen Adams

who cited the case of a 5,000 supermarket robbery which

occurred in another part of state Oct. 4. The mailed report took

three days to reach Glendale. A teletype news report

would have been seen in the Glendale station five

minutes after the robbery. |

The

officer is Sal Vetrano, it is in the new station at 7119 n. 57 Dr. so it

would be around 1963 to 1969.Thats about all I can tell you about it

aug 23 1970 even appeared in

|

Computer Controls

Police Teletype Net

Aug 23 1970 this article even appeared in Pak City Daily

News Aug 19 1970

|

Computer Controls

Police Teletype Net

By RICK COOK

Associated Press Writer

PHOENIX, Ariz. (AP) - A

computer in » Phoenix cloakroom

is helping police all over

the country fight crime more efficiently.

The computer is the nerve

center for the Law Enforcement

Teletype System (LETS) and

the cloakroom is located in the

Arizona Highway Patrol's communication

center. LETS is a nationwide

teletype system that

allows law enforcement officers

to send messages to each other.

Messages from officers in each

state are routed through the

state's central LETS office and

from there to anywhere in the

continental United States.

Until 1966, police departments

sent such messages in Morse

Code.

(no-

used paper tape

but was Baudot not MORSE!

- Ed Sharpe)

"It was pretty slow," recalled

Maj. J. W. Monschein, the Arizona

Highway Patrol's communications

officer. "We might not

get an urgent message off for

hours and we might not receive

a message for a couple of days.

Now you could hop a plane from

Phoenix to Los Angeles and my

message would be in Los Angeles

way ahead of you."

Maj. Monschein said the

LETS system was dreamed up

in 1965 at a national meeting of

state police and highway patrol

officers. The Arizona Highway

patrol was selected as the national

center because it had an

excellent communications unit.

The original electro-mechanical

system filled a good-sized

room with teletypes and tape

punchers and readers. In November

of this year the entire

system was computerized. Now

the same volume of messages is

handled by one teletype and a

|

refrigerator-sized computer console.

"Three or four years ago

when we were first putting in

the old system, we couldn't aftord

a computer," Monschein

said. "But technology has come

so far so fast that by installing

computer we actually save the

states about $1,500 a month over

the old system. In addition, we

save the Arizona Highway Patrol

about $300 a month in paper

and tape."

The system is paid for entirely

by the member states. The

only role of the federal government,

is the six thousand miles

of circuits leased, at a reduced

rate, from the General Services

Administration.

Messages for the LETS system

are punched onto paper

tape at the central outlet-entry

point in each state. At least

once every five minutes the

computer automatically "polls"

each outlet-entry point to see i*

it has any traffic. Any messages

are automatically read and

routed to their destinations.

"We use the tape because it's

faster," Monschein explained.

"No typist can keep up a rate of

100 words per minute for very

long."

The system handles about

10,000 messages a day of a police

nature. Reports of crimes,

descriptions of stolen vehicles,

reports on weather and road

conditions and a host of other

information is sent by the computer

from the people who have

it to the people who need it.

"A report of a bank robbery

in Missouri can be sent to any

state, or any 10 states or to all

states," Monschein explained.

"It can include a description of

the subjects, their mode of travel,

their direction of travel—

anything that would help law officers

to apprehend them." |

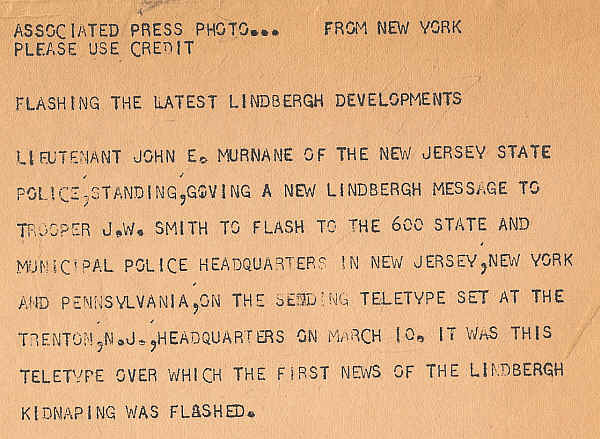

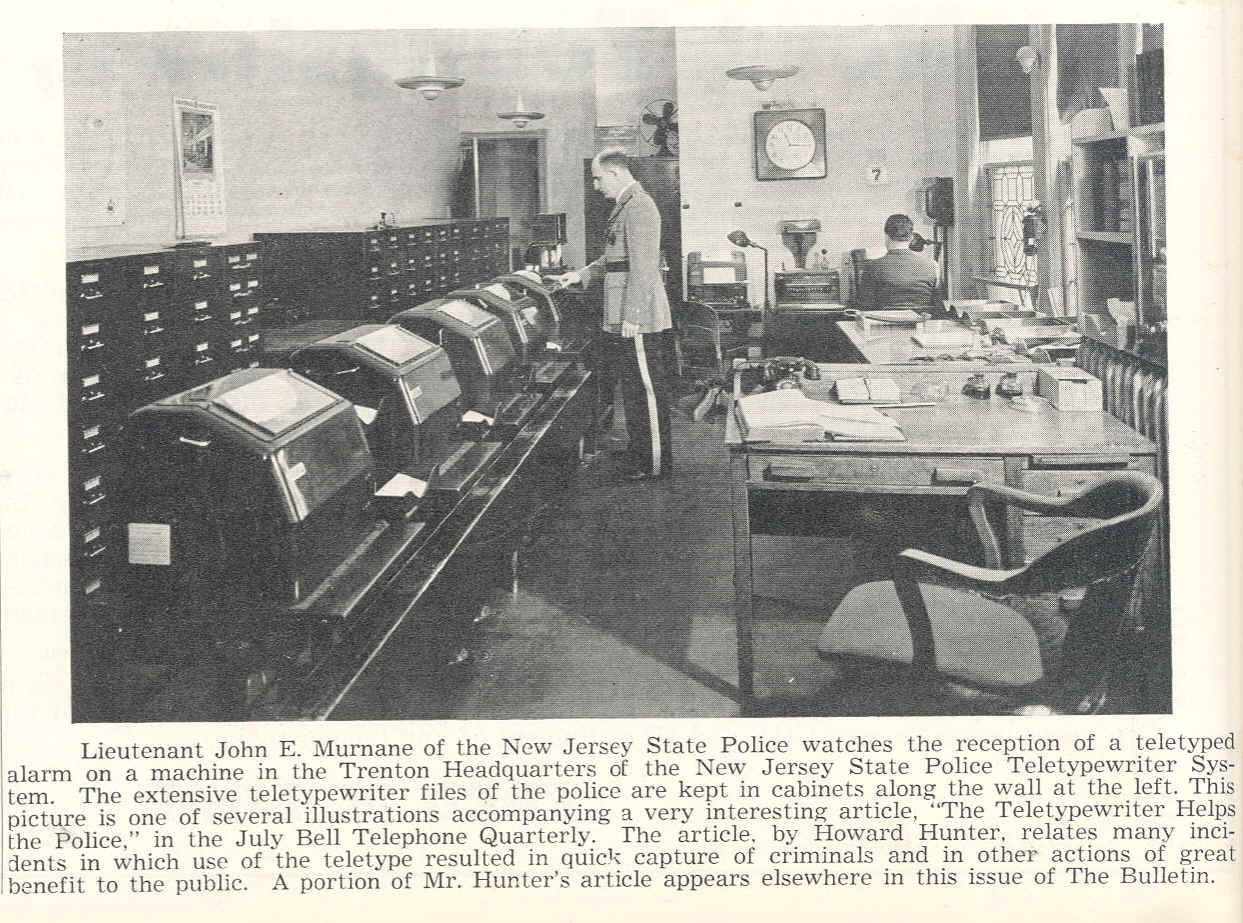

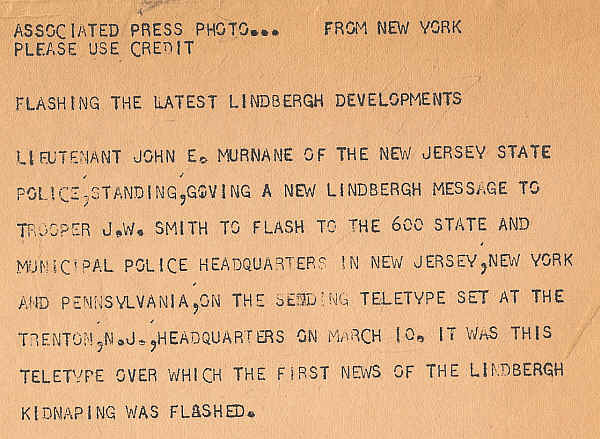

| Teletype Machines 1932 |

| Baltimore Sun Archive Photo |

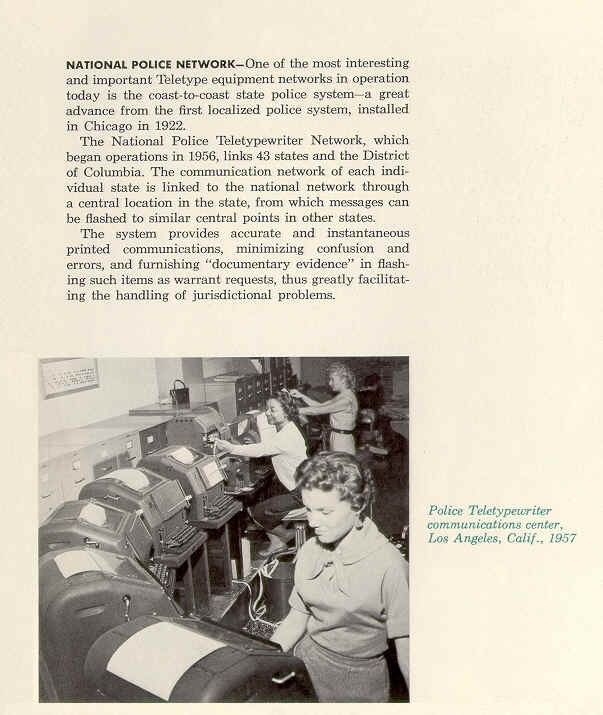

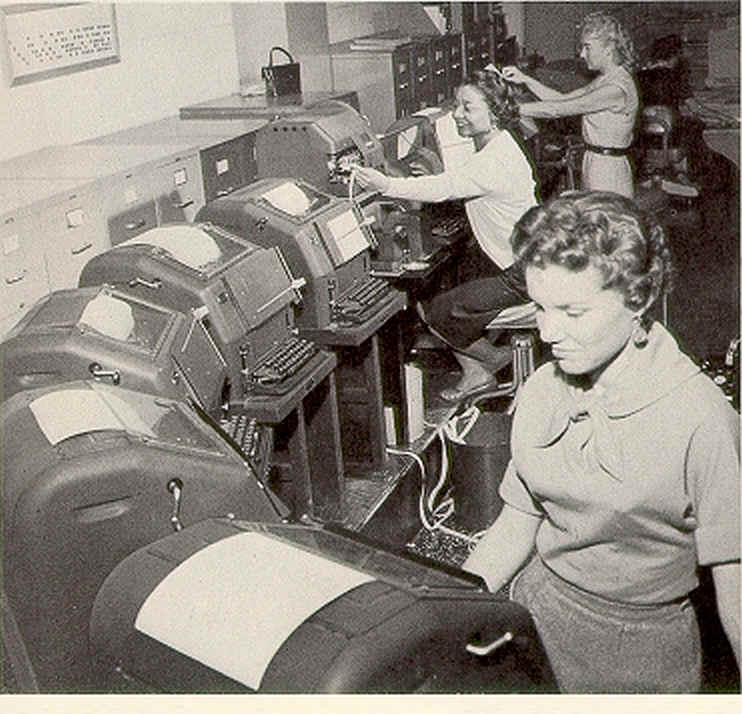

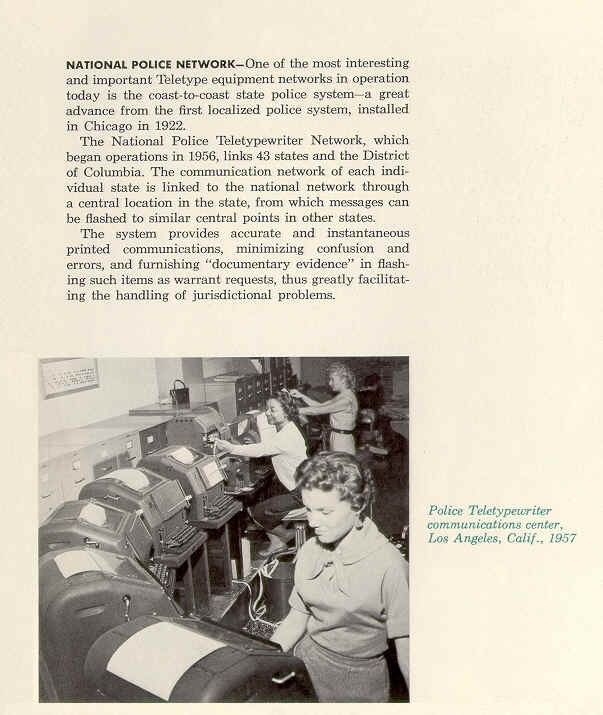

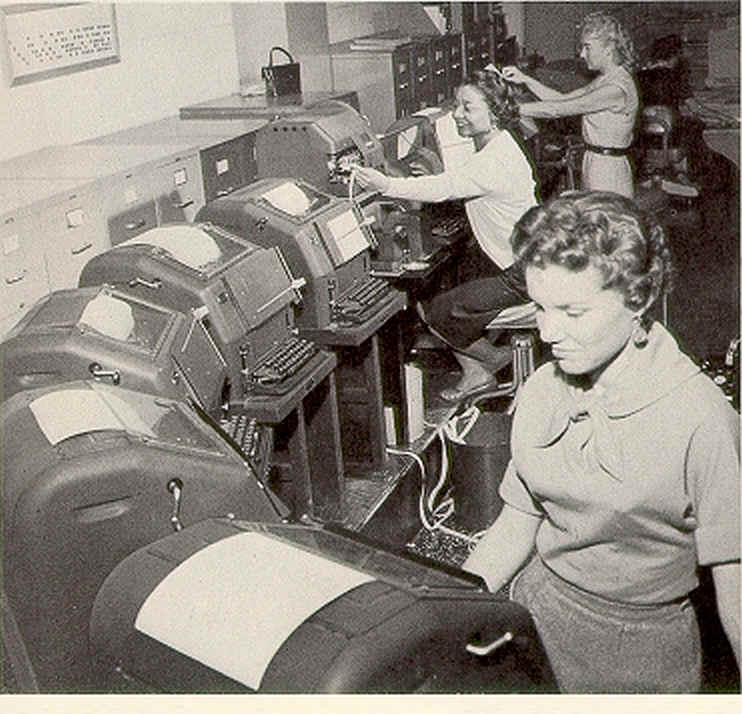

NATIONAL POLICE NETWORK - One of the most interesting

and important Teletype equipment networks in operation

today is the coast-to-coast state police system-a great

advance from the first localized police system, installed in

Chicago in 1922.

The National Police Teletypewriter Network, which began

operations in 1956, links 43 states and the District of

Columbia. The communication network of each individual

state is linked to the national network through a central

location in the state, from which messages can be flashed to

similar central points in other states.

The system provides accurate and instantaneous printed

communications, minimizing confusion and errors, and

furnishing “documentary evidence” in flashing such items as

warrant requests thus greatly facilitating the handling of

jurisdictional problems. (From

THE TELETYPE STORY - 1958)

There is a long history of teletypewriter use by police organizations.

Recently photos of TTY equipment in old police operations have been

offered on ebay.com One mention of police service in the Eastern U.S.

is given in a paper "Modern Practices in Private Wire Telegraph Service"

by R. E. Pierce of AT&T, AIEE Transactions, June 1931, p. 426.

Circa 1960 Teletype had a switching system called TASP that I was told

was marketed primarily to police departments. Some patents describing

this system are 2,625,601 (1953) and 3,251,929 (1966). It's curious that

Teletype offered such a system, since switching arrangements were usually

considered to be on Bell Labs' turf. (Or Western Union, for non-Bell

users) Teletype was allowed to do switching work for customers where

it was felt there was no general Bell System market. Therefore I assume

TASP was marketed to police (and other agencies) that wanted ownership

of the equipment rather than a leased service.

When amateur RTTY first got started in the late 1940s the majority of

Teletype machines available to amateurs were Model 12 page printers,

and most of them seemed to come out of New York. I remember reading

somewhere that most of them had come out of the New York police

department. The NYPD had replaced its tty machines out of necessity

when Teletype quit making maintenance parts for them.

jhhaynes

|

| |

| Communications and Police Protection

Bell Telephone Quarterly JANUARY

1936 -John C. Steinberg 3

EVERY invention, while adding to the comfort or welfare

of society, introduces its own peculiar problems. We

think of rapid transportation, for example, as a boon to mankind.

Primarily, it is; but, at the same time, those who refuse

to conform to society's rules of conduct make of it an aid to

the law-breaker. The modern criminal employs the speedboat,

the airplane, especially the fast motor-car and our hard

roads as means to accomplish his own ends. He has greatly

shortened the time it takes him to escape from the scene of a

crime.

While speed has been added to the kit of the up-to-date

criminal, science, fortunately, has been able to answer this

speed with more speed. Invention keeps a pace ahead of the

enemies of society. The evil-doer knows that, whereas a few

years ago half an hour or longer might elapse before a policeman

put in his appearance, it is now likely to be a matter of

only a few minutes before a dozen or more officers of the law

reach the scene. Escape time has been greatly reduced. And

this diminution has been brought about chiefly by agencies of

communication - the telephone, the teletypewriter and the

radio, along with improved techniques for their application to

law enforcement.

With time having become so important an element in the

apprehension of criminals, it is essential that the public cooperate

with police forces in order to secure the maximum of

protection. None is more aware of this fact than the police

official. Constantly, police departments urge citizens not to

delay in reporting to headquarters not only crimes which are

witnessed but suspicious persons or circumstances. The New

York City Police Department recently distributed 100,000

13

posters, appealing to the public to " Phone the Police." The

faster a report goes in to headquarters, the faster police departments

can swing into action, thus cutting down " escape time "

and making an arrest more probable.

In general, it may be said that there are three types of police

communication. First, there is the telephone. With its 87,-

000,000 miles of wire, its army of trained, alert workers motivated

by the traditional Spirit of Service, the telephone system

offers the means of making the quickest possible contact between

the public and the police. When you say to the operator

" I want a Policeman " you have taken the first necessary

step in law enforcement.

To the police forces the telephone is indispensable. Not

only do their switchboards handle the many calls from the

public but countless messages from one police official to another

go over the board.

As the police go into action in the war against crime, not

only the telephone but the teletypewriter and the radio come

into play. The telephone, the teletypewriter and radio, all

three, are swift, practical and dependable; but, the teletypewriter,

with its printed record, its duplicate copies, its ability to

receive messages at unattended stations, its secrecy and its

power to communicate simultaneously with many points over a

wide area, offers features of special value to law enforcement

bodies, and, accordingly, forms the basic system in a modern

police communication network. For establishing contact over

a limited area between headquarters and mobile police units,

such as automobiles, radio is proving of increasingly great

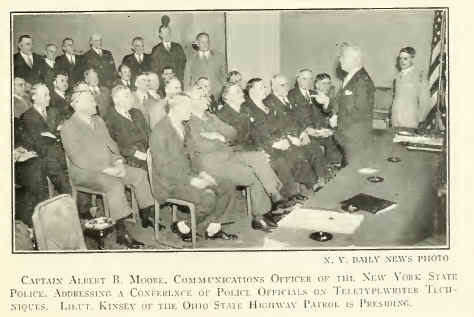

value. Captain Albert B. Moore, Inspector of the New York

State Police and Director of the New York State Police School,

who is in command of the state police teletypewriter and radio

systems, emphasizing the value of these services in a recent talk

in Richmond, Va., said:

" Police information to be of value must of necessity be accurate.

Any errors in transmission might result in serious com-

14

plications. The accuracy must be supplemented by rapidity

of transmission, and the rapidity of transmission must place

the information at all points within a given area simultaneously

in order to be of value. Criminals leaving the scene of their

operations may depart in one specific direction only to change

their course, and perhaps double on their tracks. It is therefore

obvious that all directions of the compass must be considered

in the hunt for these malefactors. . . .

" Many times I have been asked concerning the value of

radio for police work. I believe it is valuable and has its place

in any well organized communication system. Radio presents

possibilities for limited areas, but in New York state it would

be practically impossible to have one radio system capable of

reaching throughout the entire state. There are several municipal

police stations and these are having highly successful

results. However in a broad area, such as New York [state],

radio must of necessity be supplemental to teletypewriter."

August Vollmer, criminologist and former president of the

International Association of Chiefs of Police, writing (with Alfred

E. Parker) on " Crime and the State Police," says of teletypewriter

systems and other modern instruments in use by the

police: " It is this modern equipment in well-trained hands

that often enables the State Police to be so effective against

modern criminals. Perhaps this is nowhere so evident as in

the use of quick means of communication. . . . The teletypewriter

system as installed by the New York State Police is an

outstanding achievement in State Police communication."

The best equipped police forces today employ to advantage

all three forms of communication.

Teletypewriter Service

Simply expressed, a teletypewriter is an electrical device for

typewriting by wire. Perfected in 1915 (when it was known

as printing telegraph equipment) it has been continuously improved.

Today, including machines for both private lines and

15

switched service, some 1,200 teletypewriter stations provided

exclusively for police purposes are actively in use in the United

States. This number is rapidly increasing.

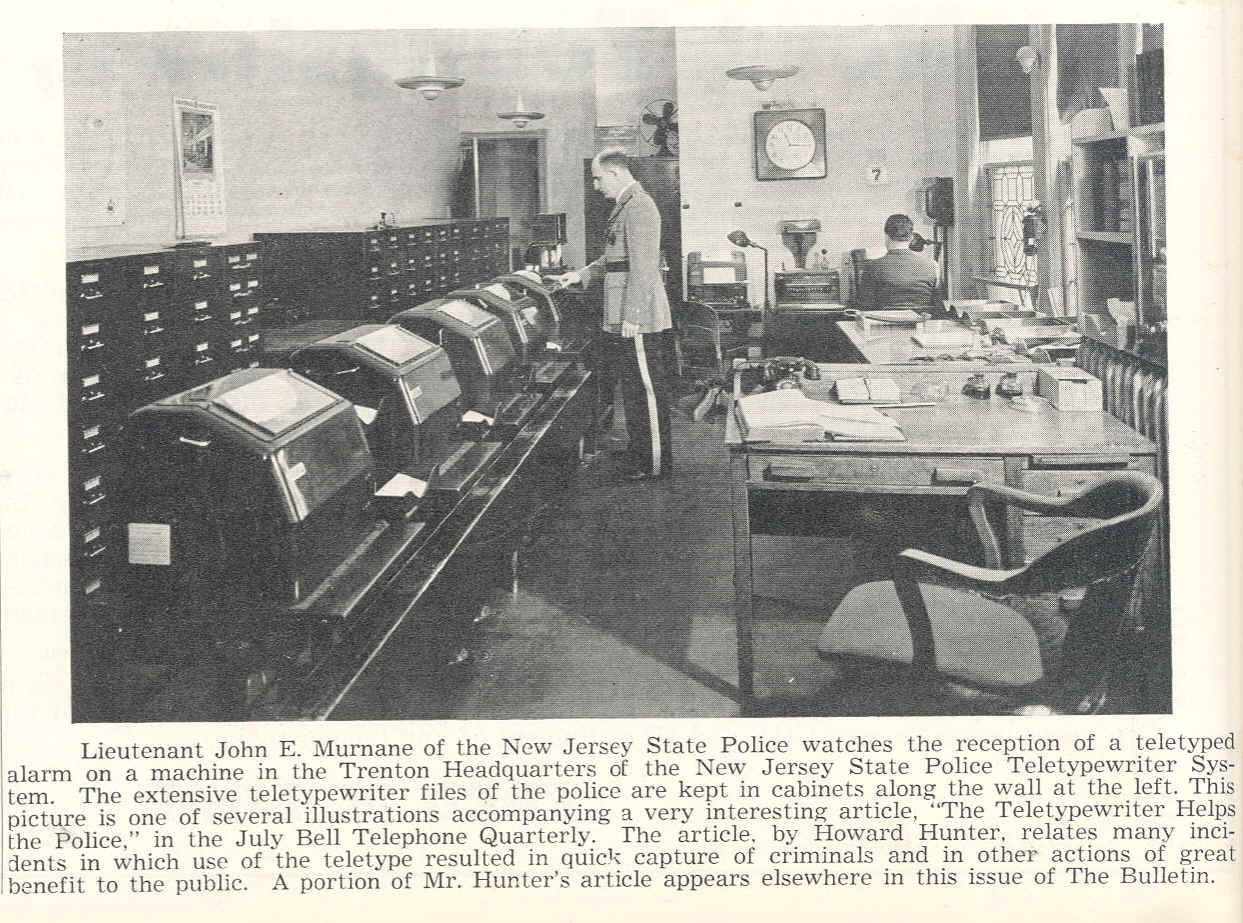

Since 1927, when various municipalities in Connecticut began

to use a private line teletypewriter system, the importance of

the device in police communication systems has steadily grown.

On December 23, 1929, the first state police teletypewriter

system was inaugurated by Pennsylvania. On October 1,

1930, New Jersey inaugurated a state-wide system, and provided

for the first interstate connection, which was between

New York City, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. In 1931 as a

demonstration there was established by private wire a police

teletypewriter hook-up of 7,000 miles, involving twelve states,

a Canadian province and fifteen cities scattered from New York

to the Pacific Coast. About a year and a half ago, the state

of Connecticut completely revamped its system and established

it upon a state basis. In the meantime, a cooperative movement

among the states in the east had been growing. The

need for rapid communication from one state system to another

had become apparent. Out of this need there developed an

eight state regional system which furnishes teletypewriter coverage

to the states of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York,

Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island with connections

to Delaware and Ohio.

It is easy to see how lessened has become the chance for the

criminal to escape in this large area, for it is possible over the

eight state hook-up for a state to flash almost simultaneously a

report on a crime to each of its teletypewriter stations and to a

police point in a neighboring state, where the report may be retransmitted

to other cities and eventually to other states. Full

coverage of the eight states for a police alarm is obtained in this

way in less than 20 minutes. Furthermore, plans are under

consideration for the establishment of teletypewriter systems

in a number of adjoining states. When these are connected,

as planned, with the existing regional system, there will be no

16

longer merely an extensive eastern teletypewriter network but

the beginning of a truly national system.

The municipal teletypewriter system may vary from a few

sending and receiving machines to the 136 in New York City.

The teletypewriter system of the Police Department of the

City of New York is, naturally, complex. The greater city is

divided into five boroughs—IManhattan, Brooklyn, Bronx,

Queens and Richmond. For each borough there is a separate

police command with a headquarters office. In each borough

headquarters there is a switchboard with tie-lines which permits

two-way service between general police headquarters in

Manhattan and the other four boroughs. Associated with the

switchboards are a total of 136 teletypewriters. This flexible

system provides that messages may be sent to any single teletypewriter

machine, to a group of machines or to all machines

connected with the switchboards; it furnishes two-way communication

between general headquarters and the other four

borough headquarters, as well as one-way communication between

each borough headquarters and each precinct in the borough.

Two classes of information are transmitted over the

system: first, that of general importance which is transmitted

by general headquarters to the other boroughs where it is

widely distributed when the precincts are involved; second,

that which concerns a particular borough. The information

thus transmitted originates from communications received at

headquarters from precinct, division or district commands, or

from reports from the public.

A good example of a county system is that which serves the

police of Nassau County. It is not only useful in the work of

protecting all sections of the townships not included within the

limits of incorporated villages (in certain instances incorporated

villages are patrolled also) but, as it is tied in directly

with the New York City police teletypewriter system and the

New York State system, it is one unit in a regional network.

The county police department is divided into six precincts

17

with headquarters at Mineola. The system consists of a 20-

line switchboard at Mineola from which two-way circuits are

extended to each precinct headquarters, terminating in receiving

and sending instruments. The switchboard is so arranged

that the operator may send or receive messages to or from any

station connected with the switchboard. Messages may also be

sent simultaneously to a selected group of stations or to all stations

in the system.

With the New York City system, the Nassau County system

is connected by two one-way circuits. The circuit from Mineola

to New York City terminates in a receiving only machine

at Manhattan headquarters, while a circuit from Manhattan

headquarters terminates in a receiving only instrument at

Mineola.

These municipal and county systems are, generally, connected

with each other and with the state systems and are tied

in by direct teletypewriter circuits with the systems of neighboring

states. In many instances, they are supplemented by

strategically located police radio stations.

The state of New York dispatches over its teletypewriter

system more than 250,000 communications each year. Of

these, about fifty per cent are concerned with automobile registrations

and requests for data, stolen cars, recovered cars, hit

and run drivers and emergency notices to automobilists. Another

ten per cent is accounted for by reports on missing persons,

with about forty per cent devoted to the more spectacular

misdeeds and routine administrative business. The dramatic

crime is relatively rare. Its scarcity may be due somewhat to

the preventive factor present in modern police communication

systems. Police officials are convinced that the knowledge of

the existence of modern communication equipment in a given

area acts as a crime deterrent.

The teletypewriter is admirably suited to the handling of

that vast amount of police business of which the public does

not hear. In many cases, an instrument is stationed in the

18

state's motor vehicle bureau so that data needed by the police

can be obtained promptly and reported back.

Most police teletypewriter systems are set up on a private

line basis. However, a certain limited use of Teletypewriter

Exchange Service has developed since 1931 when the latter

service was introduced.

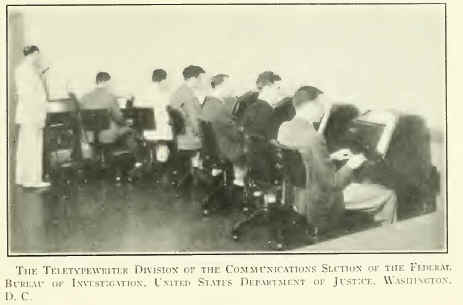

One of the most interesting of recent installations is that of

the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the U. S. Department

of Justice. Teletypewriter Exchange Service (familiarly

known as TWX) was placed in operation in 1935 for communication

between the Bureau's Washington headquarters

and its 36 field offices located in other strategic cities throughout

the country. There are four machines in the headquarters

office at Washington, two each in the New York, Chicago and

Philadelphia offices, and one each in the remaining field offices.

When the Bureau's Director, J. Edgar Hoover, or a member

of his staff in Washington wants to communicate with the field

in which are operating 500 specially trained men—the famous

" G-men "—the procedure is somewhat as follows:

In the communications section of the Bureau in Washington,

one of the men assigned to the work throws a switch on one of

the machines. When the TWX operator indicates that she is

ready, the Bureau operator types, let us say, Denver 0711.

When, a few moments later, a bell rings in the Denver office

there will be some one on duty to handle the call, for all the

field offices, in charge of special agents, are open day and night.

The field operator establishes connection and the Denver

machine is ready to reproduce the message typed in Washington.

Again, Washington may want to be in touch with all 36 field

offices at one time. There may even be additional temporary

offices with which headquarters wants to communicate while

addressing the field. Swiftly, Bell System operators go into

action. Following a carefully formulated plan, they set up a

conference TWX circuit linking the Washington office, over

19

hundreds of miles of wire, with every field office. In less than

half an hour, every teletypewriter in every field office is simultaneously

clicking off the Washington report. The communication

may have to do with a matter of administrative routine,

with a robbery or a kidnaping, with any one of hundreds of

crimes to which the G-men may be assigned.

The Bureau, of course, makes extensive use of the long distance

telephone. Its speed, privacy and suitability to personal,

two-way discussion commends it. When, in addition to speed,

privacy and the two-way channel, it is desirable that the message

be transmitted in written form, TWX service efficiently

meets the need.

The following actual case is a good example not only of cooperation

between different police organizations but of the

value of the teletypewriter in spreading information quickly

over a wide territory.

Four men broke into a jewelry shop in Beacon, N. Y. Local

police surprised the thieves and managed to catch one. The

other three escaped in an automobile, taking the road for New

York. Immediately a message was dispatched over the state

teletypewriter system by the State Police at Fishkill. The

robbers were sighted once again on their dash southward and

an added alarm was teletyped concerning them. By the time

the fleeing thieves reached Yonkers, practically every peace

officer in the county and every police officer in New York City

was on the lookout for them, having been warned by teletypewriter

messages relayed by radio to patrol cars or by telephone

to call-boxes.

Charles Smith, Westchester County Parkways patrolman,

encountered the robbers in Yonkers. He waved them to a stop

but they answered by firing their revolvers at him. Smith

gave chase on his motorcycle and forced the speeding car into

a ditch.

A hand to hand combat ensued. Smith caught one of the

20

trio, but the other two broke away and, commandeering a taxicab,

started once more for New York.

The taxi-cab was halted finally by New York City police.

Once more there was an exchange of revolver shots. This time

the police killed both the bandits.

Another actual case, in which telephone, teletypewriter and

radio dove-tailed, is that of Robert J. Mahoney who shot State

Trooper George Doring in Sudbury, Mass. Five hours later,

Mahoney was dead in Leicester, Mass. Trooper James H.

O'Neill had brought him down.

Trooper Doring had called on Mahoney to halt. Mahoney

replied by firing at him and wounding him. The gunman, a

girl beside him in his car, roared down the road toward Worcester.

" Within five minutes after the shooting of the policeman," said the

Worcester Telegram, " the Framingham barracks of the state police had

established contact with troopers on patrol. Two men were assigned to

watch the Post road and question all persons answering the description

given. One trooper was posted near the scene of the attack. . . . Garages

and call stations were notified to flag all the passing troopers and to direct

them to call in immediately.

" Automobiles equipped with radio receiving sets were immediately contacted

as they cruised through the Lake Boone region. Those troopers

learned of the crime within ten minutes of its occurrence.

** The teletype switch was throwwn open and a white light glowed over

' Framingham ' on the switchboard in the State House headquarters of the

State police patrol. An operator pulled a switch on the teletype machine

and a policeman in the Framingham barracks began his story. The story

was in cold type almost as soon as one could tell it. The operators threw

down the plugs to Holden, Middleboro and Northampton. Over the

wires to these stations went the news of the shooting.

" At Framingham the telephones rang loudly as the troopers called in

from garages and call stations. Nine men were ordered to Worcester to

find the missing bandit and bring him back. They started for Worcester

while 23 men whirled out of the substations at Reading, Concord, Topsfield

and Wrentham. ... In the meantime at Holden the teletype was

grinding out its story."

21

From the north, east, west and south the troopers came,

called by the teletypewriter, telephone and radio. Finally, a

hundred men were involved in the hunt. The bandit was

bottled up somewhere near Worcester. Every avenue of escape

was closed. It was only a matter of time before Mahoney

was caught.

At Spencer the engulfing waves of troopers met. Mahoney

was surrounded. He wrecked his car against a stone wall, injuring

his girl companion, and took to the woods, alone and on

foot. He ducked and dodged. He tried to steal a truck and

failed. From another truck he got a short ride. At Leicester,

he was on foot again, crawling through back-yards. He

climbed the fence at the Leicester Tavern. Trooper O'Neill

of Holden saw him. He called to him, then fired. Mahoney

toppled. O'Neill went after him. Lieutenant Shimkus and

Sergeant Sullivan ran up. Mahoney had crawled to a cellar,

leaving a trail of blood. Shimkus called on him to surrender.

The bandit, his voice choking, refused and fired at the officer.

The Lieutenant rushed upon him and disarmed him. Mahoney

lost consciousness and died half an hour later.

In the words of the Worcester Telegram: "A bullet killed

him, but radio and teletype and telephone had already doomed

him."

Since 1921, when the Detroit Police Department began its

experiments, an increasing number of law enforcement units

have been making use of radio. At the close of 1935 there

were in operation more than 60 city, county and state Western

Electric Police Radio Systems, as well as others manufactured

by other companies, all of them getting cars full of police officers

to scenes of crime within two or three minutes after the report

had been received at headquarters. Police radio is giving

added protection to 35 million people.

22

|

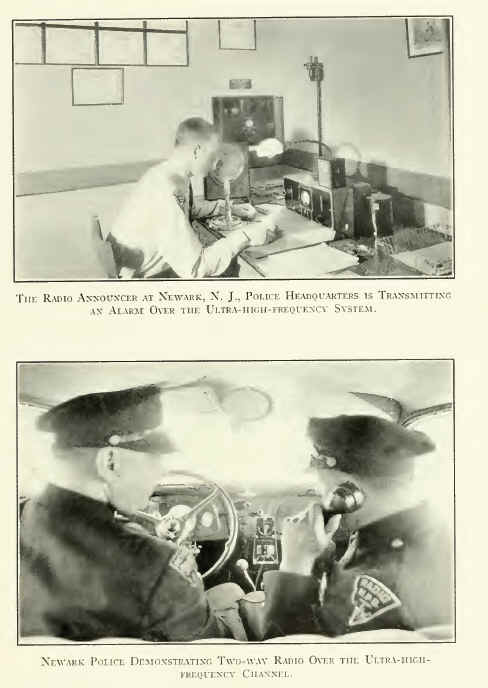

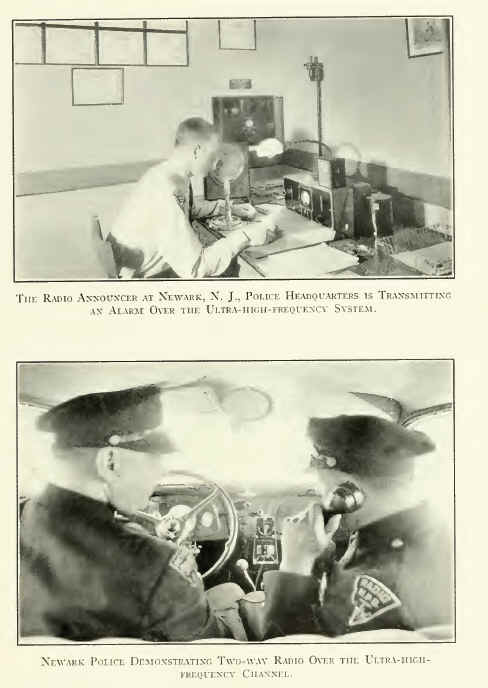

Two-Way Police Radio

In the spring of the same year, Bell System engineers contributed

to the war against crime one more important weapon.

This is a Two-Way Police Radio, a great advantage to peace

officers in a limited area. With this equipment, the motor

patrolman not only receives alarms but he may acknowledge

them, request further instructions, report crimes or suspicious

persons or circumstances, may inform headquarters of his position

and progress on an assignment—all, without leaving the

wheel of his car.

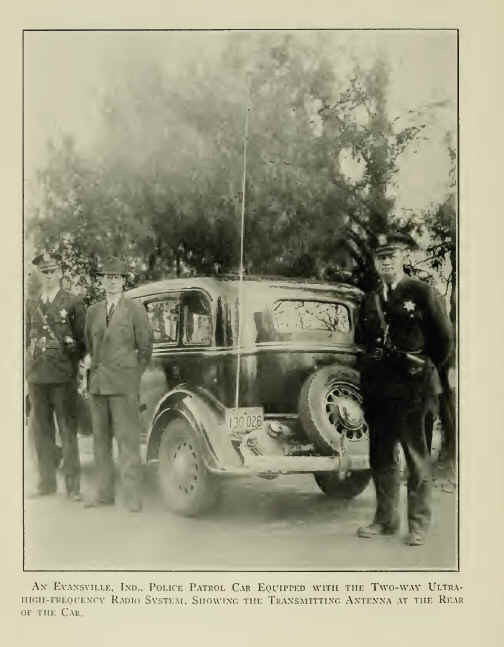

The first installation of the new system was in Evansville,

Indiana. Westfield, N. J., Morristown, N. J., Manchester,

N. H., Elgin, 111., Wheeling, W. Va., and Nashville, Tenn., are

scheduled to have two-way equipment in operation in the near

future.

Statistics covering five months of operation in Evansville are

startling. They reveal a decrease in crimes of 17 per cent and

an increase in arrests of 60 per cent, following the introduction

first of one-way and later of two-way police radio.

The two-way system operates on ultra-high frequencies in

the band of 30-42 megacycles. In addition to a transmitter

at headquarters and receivers in the patrol cars, it includes

specially designed transmitters for the cars and a receiver at

headquarters. The car transmitters, weighing only 20 pounds,

are only 11 by 7 by 6>4 inches in size and yet are held to within

.025 of an assigned frequency by a new type of crystal with a

low temperature coefficient.

A flexible steel rod, projecting slightly above the top of the

car, acts as a vertical antenna which transmits as well as receives.

On the dashboard hangs a telephone, much like the

familiar hand-set, and the patrolman's voice speaking through

it operates relays which put the car transmitter on the air.

These relays are so timed that they do not switch off during

intervals between words but do so after the brief pause which

23

shows that the speaker has finished. The car receiver then

automatically goes into operation and is ready to pick up messages

from headquarters.

Most police radios operate on a medium frequency band,

roughly from 1,600 to 1,700 kilocycles and from 2,300 to 2,500

kilocycles. With an eye to the crowding that might take place

within that narrow range, the Federal Communications Commission

recently assigned to police work experimentally, an

additional band which ranges from 30,000 to 42,000 kilocycles.

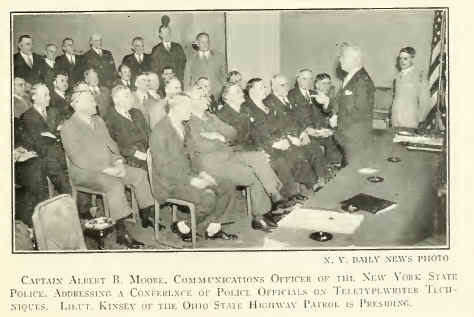

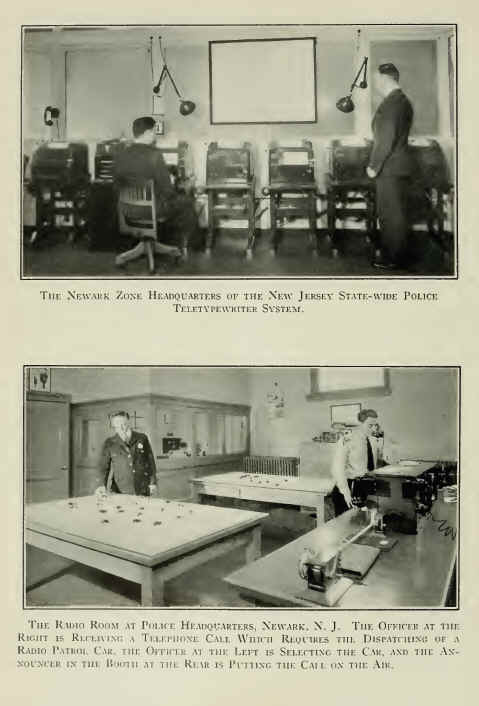

The system of the Police Department of the City of Newark,

N. J., among the most up-to-date one-way installations in present

use, operates in the new high frequency band on 30,100

kilocycles.

For municipal stations, there are certain advantages in ultrahigh

frequency operation. Freedom from atmospheric disturbances

is one. No static, or thunderstorms will trouble the

ears of the motor patrolmen.

As wave length determines antenna length, Newark is able

to employ a short section on the 100 foot flag pole atop the

city's tallest building, the National Newark & Essex Bank

Building. Conversion to two-way service would, should authorities

determine upon it, be very simple as the car transmitters

could operate on the wave length which the station now

uses. Short waves do not carry great distances from such

stations. For State Police work two-way radio, because of

limited range, is not now developed so as to be practical. The

limited range has an advantage, however, in that a city as close

to Newark as Albany probably could use the same wave length

without overlapping. However, as the separation between

ultra-high frequency channels is very narrow all apparatus, to

perform successfully, must be of great refinement, stability,

selectivity and reliability.

Put into service on October 3, 1934, by Director of Public

Safety Michael P. Duffy, the radio branch of the Newark Police

Department has made enviable records not only in efficient

24

law enforcement but in overhead cost reduction. Said the

Newark Ledger recently:

" The radio division has made 849 arrests, extinguished 55 fires, saved

more than 40 lives and recovered stolen property valued at ?1 15,002. . . .

" In 1931 there were 110 more men in the police department than there

are today. Radio made it unnecessary to replace them upon retirement.

Figuring on a base pay of $2,300, saving of their salaries means more

than $250,000 in the annual running expense of the police division.

" In addition Duffy was able, due to the wide scope that one car can

handle, to abandon four police precincts.

" Several months ago, the director shut down the Fifth, Sixth, Seventh

and Eighth Precinct Station houses. * These properties will be put on

sale when the real estate market improves,' Duffy said.

" ' That means the property will once more become taxable and will

show in the ratables.'

" Case records kept by the radio division tell an interesting, important

tale.

"'On Nov. 8 at 1:44 P.M., car 42 was sent to 52 Littleton Avenue,

where a thief was ransacking the premises. The house was covered front

and rear and a radio patrolman entered the front door and arrested the

burglar. At 1:48 P.M., a patrol wagon was summoned to take the prisoner.

The man has a criminal record.'

"'On Dec. 11 at 10:15 A.M., car 52 noticed smoke coming from a

house on North Seventh St. A patrolman entered the building and

brought a 90-year-old man and an infant to the street in safety. In

doing so he was overcome by smoke and received treatment at City

Hospital.'

" ' On Dec. 6 at 11:43 P.M., two cars were sent to a Sumner Avenue

building where a woman was about to commit suicide by leaping from

the roof. Car 22 arrived at 11:45 P.M. and took her from the roof in

safety.'

" ' On Nov. 18, radio car 52 noticed auto parked near Bloomfield city

line. Two men were in car. Officers investigated and found car contained

sawed-off shotgun, an automatic revolver, and burglar tools. The

men admitted a plan to hold up a gas station.'

" These are only a few of the tasks the radio men have performed successfully."

A review of recent developments in methods of exchanging

intelligence among law enforcement units, indicates that to

25

the constant war against crime the art of communication has

made two most valuable contributions. First, through virtually

universal telephone service it enables the public quickly

to give an alarm. Second, through teletypewriter and radio

it allows the authorities to take rapid action upon the receipt

of the alarm and, if need be, to spread information far and

wide with little or no loss of time.

To the long arm of the law has been added a voice. And

that voice, whether it be the 24-hour a day chattering of the

teletypewriter, the staccato bark of the radio or the familiar

ring of the telephone, is daily putting fear into the hearts of

criminals and making life safer for the public.

Sterling Patterson

26

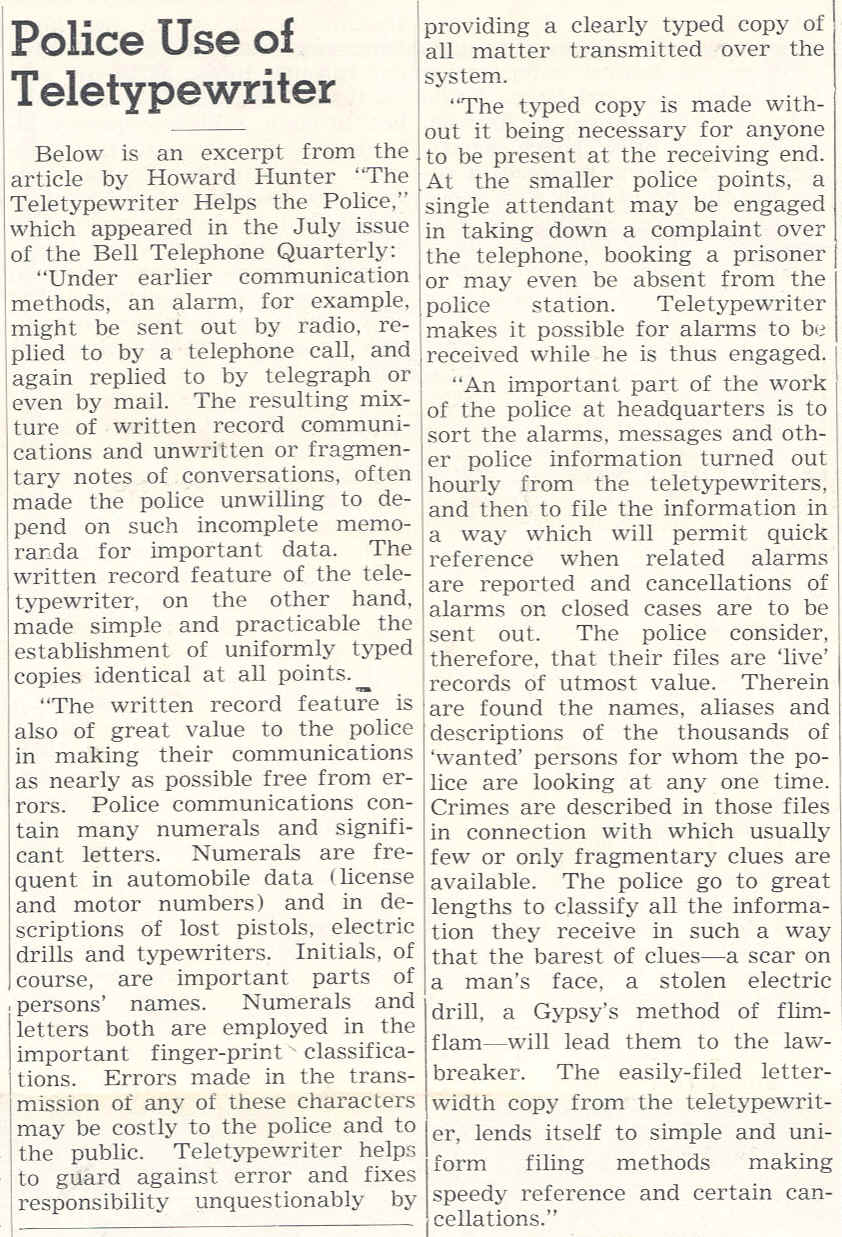

The TtLETVPEwraTF.R Division* of the Communications Section of the

Federat,

BiREAu OF Investigation, United States Department of Justice, Washington,

D. C.

N. Y. DAILY news PHOTO

Captain Albert B. Moore, Communications Officer of the New York State

Police, Addressing a Conterence of Police Officials on Teletypewriter Techniques.

Lieut. Kinsey of the Ohio State Hic.hw.ay P.^trol is Presiding.

Ax Ev.\Ns\ II i.K, Im).,

Police Patroi. Car Equipped

with iiii.

Twu-ww Ui.tra-

HIGH-FREQIIENXY RaDIO SySTEM, SHOWING

THE TRANSMITTING AnTENNA AT THE

Rf.AR

OF TiiK Car

|

1935 Police Demonstrate

Teletype

|

| |

|

|

telephones to his local police department and reports that his

automobile has disappeared. He tells the police the make,

year, color, and the license and motor numbers of the car. A

police officer types out the alarm on the keyboard of the teletypewriter.

The keyboard is similar to that of an ordinary

typewriter and as each letter is depressed at the home machine,

the corresponding letter is typed on all other machines which

may be connected to the circuit. The copy thus typed out (at

speeds up to 60 words a minute) is letter width size, and frequently

the machines are arranged to provide carbon copies at

some of the larger police points where extra copies of alarms

and reports are of advantage to specialized police groups, such

as the automobile, homicide and missing persons squads.

The alarm thus typed out reads as follows:

STOLEN CAR, REGISTRATION B-12974 BUICK 1938 SEDAN,

BLACK, MOTOR NO. 9870482.

This alarm, when it is received at the headquarters of the

state system is consolidated with other stolen car alarms and

the combined information started on its way to points throughout

the state and to the other states in the network. Key

points in the neighboring states receive the various alarms.

The key points in turn spread the alarms throughout their own

states and to other states to which there are teletypewriter connections.

County and city systems carry the report to precincts

and station houses. The information as to the stolen

car may in this way be known within 15 minutes to detective

bureaus, automobile and traffic squads, Motor Vehicle Bureaus

and State Police troopers throughout the eight states.

When the state police stations receive an alarm over the

teletypewriter system, they post the car number in the barracks

where the troopers may take note of it as they come from or go

on duty. Municipal police units note the alarm on the " blotter."

The alarm is read to the shifts next going on duty together

with other alarms, police reports and instructions. Men

169

detailed for traffic duty jot down the car numbers contained in

the alarm before they go on shift. Motorized traffic police

sometimes carry the information, given by the alarm, on a card

placed under the transparent backing on one gauntlet, or the

original teletypewriter copy may be carried in this way. When

the hand is raised to halt a car, the wanted car number is in

easy line of sight with the license plate of the stopped car.

Besides being telephoned to other police points, the teletypewriter

alarm may be passed to motorcycle officers through the

device of telephoning roadside gas stations, dining places or

refreshment stands, to " flag " the officer to stop and receive the

message. A ''disk" or flag sometimes is displayed for this

purpose. State and municipal police points equipped with

transmitting equipment, relay the teletypewriter alarm by

radiotelephone to police in automobiles in the city and on the

highways.

Reproductions of several police alarms are shown herewith in

illustrations and in the text. While the alarms are actual

police records, the names of the people concerned have been

deleted and wholly fictitious names substituted in their place.

PoiNT-To-PoiNT Police Information

In addition to the flow of alarms to all points, the various

state-wide police teletypewriter systems carry many criss-crossing

queries and answers as clues are hurriedly sought, suspects

examined and " tips " passed from one police force to another.

Speed is again the important thing in this traffic. Some of

the thousands of such messages read as follows:

Information please on 4NY19-18.

Please forward fingerprints of Van Doran killed by Capt. Williams

of your department during holdup. We have several chain store robberies

and would like to check on this man.

170

Be advised that the Russell Kelley wanted by you may be in possession

of a Packard Coupe color gray registration E-45909 on door are

initials " R. J. J." Stolen from this city March 30.

"Look-ups" directed to automobile bureaus, such as the

first message illustrated above, result in replies which give

to the police information as to the make, color, year, model,

engine and serial number of the the cars bearing the indicated

license numbers. These records also show which cars have

been reported stolen. Forgeries of automobile registration

certificates, transferred license plates and mutilated engine or

serial numbers can thus be detected almost immediately. Similarly

the police send requests for " look-ups " to the motor

vehicle bureau for data on the holders of motor vehicle driving

licenses. Forged operators' licenses are easily detected and

frequent offenders readily identified through these requests.

Private line teletypewriter service is a direct path into the

motor vehicle and police departments connected to the system,

for the exchange of this kind of information.

Finger-Print Records

The value of the rapid transmission of fingerprint information

between police departments is one whose importance is

clear to all. That this information may be transmitted by

teletypewriter is not, however, generally known. Letters and

numerals are used to describe the characteristic form and number

of the lines in the print of each finger; for example, U and

R indicate, respectively, the fingerprint "ridges " flowing in the

direction of the ulnar and radial bones of the arm, while the

figures designate the number of these ridges which may be

counted between certain reference points in the print. A substantial

use is made of the eight-state system for spreading

alarms containing fingerprint information. The following is a

fingerprint record as transmitted over the police teletypewriter:

172

THUMB INDEX MIDDLE RING LITTLE

RIGHT U-11 U-9 U-12 R-8 U-10

LEFT R-5 R-10 U-12 R-11 U-9

Coordination with Other Communication Methods

The police use various other communication methods to

spread alarms. The use of radiotelephone to flash alarms to

police cars from headquarters has already been mentioned.

There is also an exchange of alarms between the police on the

Eight-State Teletypewriter System and radiotelegraph stations

of the police located in several mid-west cities. This exchange

is carried out by the municipal police department at Buffalo,

New York.

The police also make a wide use of the telephone for communication

with points not connected to the teletypewriter

network. Police points receiving alarms via teletypewriter,

frequently relay these alarms to other strategic non-teletypewriter

points by telephone. An instance of the use of the

telephone in this way, was the arrest of the robbers of the Bank

of Katonah, N. Y., when the police of the small village of

Armonk, N. Y., 15 miles away, acting on a telephoned alarm,

dragged the wanted men from under the rumble seat cover of an

automobile and recovered a paper bag containing $18,000 taken

from the bank a half hour earlier. Small police departments

without teletypewriter service, or equipped only with teletypewriters

for receiving, often telephone in their alarms and requests

for information to a two-way police teletypewriter station,

at which point the communications are transmitted over

the state-wide system. The New Jersey State Police zone

headquarters at Newark handles annually upwards of 39,000

such requests from the police of 60 neighboring communities.

The telephone is also used to take advantage of the quick, personal

contact afforded by this form of service in those matters

which require discussion and interchange of views between

police officials.

173

Telegraph message service is also used by the police, as for

example, when the police of distant cities are to be informed of

arrests which have been made, especially those made as a result

of an alarm sent out by the distant department. Data as to

criminal records and fingerprints are also often furnished in

this way. Missing persons from the smaller cities are often

reported by telegraph to the police of the larger cities, such as

New York, Chicago and Los Angeles.

Teletypewriter Exchange Service, as already mentioned, is

sometimes used to communicate with the Federal Bureau of

Investigation in exchanging identification information. It is

also used to communicate with certain other police points in

states with no private line networks.

Mail is also used extensively for nation-wide broadcasts of

alarms, where descriptions of wanted persons are sent to thousands

of post offices and police departments.

Systematizing Communication by Teletypewriter

Under earlier communication methods, an alarm, for example,

might be sent out by radio, replied to by a telephone

call, and again replied to by telegraph or even by mail. The

resulting mixture of written record communications and unwritten

or fragmentary notes of conversations, often made the

police unwilling to depend on such incomplete memoranda for

important data. The written record feature of the teletypewriter,

on the other hand, made simple and practicable the

establishment of uniformly typed copies identical at all points.

The written record feature is also of great value to the police

in making their communications as nearly as possible free from

errors. Police communications contain many numerals and

significant letters. Numerals are frequent in automobile data

(license and motor numbers) and in descriptions of lost pistols,

electric drills and typewriters. Initials, of course, are important

parts of persons' names. Numerals and letters both are

employed in the important finger-print classifications. Errors

174

made in the transmission of any of these characters may be

costly to the police and to the public. Teletypewriter helps to

guard against error and fixes responsibility unquestionably by

providing a clearly typed copy of all matter transmitted over

the system.

The typed copy is made without it being necessary for anyone

to be present at the receiving end. At the smaller police

points, a single attendant may be engaged in taking down a

complaint over the telephone, booking a prisoner or may even

be absent from the police station. Teletypewriter makes it

possible for alarms to be received while he is thus engaged.

An important part of the work of the police at headquarters

is to sort the alarms, messages and other police information

turned out hourly from the teletypewriters, and then to file the

information in a way which will permit quick reference when

related alarms are reported and cancelations of alarms on closed

cases are to be sent out. The police consider, therefore, that

their files are "live" records of utmost value. Therein are

found the names, aliases and descriptions of the thousands of

" wanted " persons for whom the police are looking at any one

time. Crimes are described in those files in connection with

which usually few or only fragmentary clues are available.

The police go to great lengths to classify all the information

they receive in such a way that the barest of clues—a scar on

a man's face, a stolen electric drill, a Gypsy's method of flimflam—

will lead them to the law-breaker. The easily-filed

letter-width copy from the teletypewriter, lends itself to simple

and uniform filing methods making speedy reference and certain

cancelation possible.

Teletypewriter Helps in Many Types of Police Work

Improved results in police operations, attributable to the use

of teletypewriter, have strengthened police hands to the point

where crooks often think twice before deciding to rob a particular

bank, or gas station because troopers or other police

175

dant for the few dollars which could be obtained. In cases

like this one, the police are usually without information as to

the direction taken by the boys. Through rapid blanketing of

the eight-state area by teletypewriter, however, the police in a

nearby state were enabled to arrest the boys before they could

commit other and more serious crimes.

Turning to some of the work the police do which is of a noncrime

nature, the teletypewriter is found to enable police to

perform many additional services of great value to the public.

Some of these services could hardly have been rendered through

any other agency than the state police. In one such case from

the records of the police, in which again the blanketing value of

teletypewriter service was demonstrated, a baby's life was

saved from poisoning. The police alarm, teletyped in all directions,

was as follows:

8-State Alarm—please stop a Chevrolet car license G ^\V

Motor 8 , car is occupied by a man named C. E. B. with

his wife and baby. They took a bottle supposed to be medicine

contents of which was to be administered to the baby. The

bottle they have contains poison—1 per cent, atropine sulphate.

Poison bottle was taken by them by mistake please make every

effort to stop this car and warn them of danger. If supposed

medicine has already been administered to the baby use any

emetic as antidote.

An hour after this alarm had been sent out a patrol nearly a

hundred miles distant from where the error had been made

recognized the car. The " cancelation " which followed said

" Baby out of danger, only one small dose of poison administered."

Helen , a demented woman, visiting in a seaside resort,

had nearly asphyxiated herself and 5 children she had with her,

when police of a nearby state, acting on a teletyped alarm from

her home city nearly 200 miles away, broke into her boarding

house room in time to save all six lives. It had taken only an

hour for the police to find her. No one knew where she was.

178

THE TELETYPEWRITER HELPS THE POLICE

The police in her home city had sent the teletyped alarm in all

directions on the eight-state system. The police in the resort

spotted her parked car by its license number and a few inquiries

led them to her room in a nearby boarding house.

Agnes was identified by the police of a New England

city from information contained in a teletyped alarm describing

an amnesia patient in a hospital located in another State

in the system. Police who found her did not know where she

belonged, but the teletyped alarm to all police departments of

the eight states furnished the right clues to the proper authorities.

Other examples are given in the accompanying reproductions

of actual police messages. Used freely by the police

of all the connected communities, the eight-state system thus

aids the police in solving the innumerable routine cases which

form a large part of their day-to-day activity.

Teletypevi^riter Benefits from Police Cooperation

While teletypewriter and radio have been important factors

in making it possible for the police to cooperate actively, the

effectiveness of these communication systems is due in large

measure to the attention which the police officials in charge of

the systems have given to the many problems involved in exchanging

information between various states. In working out

suitable procedures for handling the interstate traffic, police

officials concerned with the operation of the eight-state network

customarily meet once a year for discussion of their

communication problems at a Teletypewriter Supervisors' Conference

in New York City. Many of these officials are also

members of the Associated Police Communication Officers,

a national body of police officials primarily concerned with

radio and teletypewriter communications. The two organizations

work closely together through joint committees established

for the study of traffic problems and the legal and other

179

questions looking toward the more expeditious and accurate

handling of police teletypewriter and other forms of communications.

In reviewing the place of teletypewriter service in police

work, it is evident that the police have need for an alarm distribution

system which will deliver alarms in volume, immediately,

over great distances and to a large number of police

departments. The broader such distribution is the greater is

the chance that the criminal will be apprehended.

With teletypewriter service the police now send their alarms

far beyond the range of earlier methods, almost instantaneously,

and to hundreds of places simultaneously. Police work

as a result has been made increasingly effective as the long

arms of the teletypewriter systems reach out to guard in an

ever greater area the lives and property of millions of people.

The teletypewriter in police hands thus is one answer to the

underworld's challenge to the safety of society, and an invaluable

aid in crime prevention.

Howard Hunter

180

|

| |

|

SOUTH DAKOTA TELETYPE STUDY

NCJ Number: 68867

Author: S FLYGER; L MERRICK

Publication Date: 1978

|

|

GET FULL>> PDF

Abstract |

|

POLICE TELECOMMUNICATION SYSTEMS

NCJ Number: 341

Author: ANON

Publication Date: 1971

|

| GET FULL>>

PDF

Abstract |

|

| |

|