|

Congratulations

are extended to two GE/Process Computer engineers. Both are presented

Patent Awards which include, in part, GE stock. At left is R. M. Berling,

I.E.E.E., who invented a clock generator circuit, and right, S. A. Harmon,

who invented a "Three phase Unbalance Protector." Bernard

Adler, I.S.A., Manager of Engineering  |

|

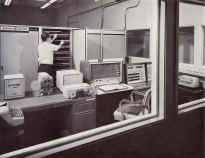

Megabytes for metals: development of computer applications in the iron and steel industryBy Jonathan Aylen *1Learn about early process control and steel making in the UK GE 412 Computer |

|

|

|

Charlie Chaplin Meets ET, the Welsh Origins of the Modern Automated Factory

Stephen Spielberg's dad and a small publicly owned Welsh steel firm seem an improbable combination. Yet forty years ago their close encounter transformed our lives with the first large scale marriage between mass production and digitisation.

Digitisation is now in full swing: Familiar consumer products such as cameras, video recorders, radios and mobile phones have gone digital in the past ten years. Yet, the digital revolution in manufacturing is of long standing, especially in chemicals and steel. Comprehensive factory automation is now forty years old. Full computer control of a large scale manufacturing plant, the hot strip mill at Spencer Steel Works, Llanwern in Wales commenced operation in October 1964.

Mass production is not new: Another father of a famous son, Marc Isambard Brunel used machine tools for mass production of wooden blocks for sailing ships at Portsmouth Naval Dockyard at the end of the eighteenth century. The real upsurge in mass production is associated with the USA in the 1920's. The trend was sufficiently well established to be satirised by Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times, released in February 1936.

The steel industry pioneered the use of computers for automation. By the mid-1960's, a fifth of the world's process control computers were installed in the steel industry. Steelmakers exploited second generation computers which used transistors as the basis for reliable mainframe computing and magnetic core memory storage. General Electric were the leading computer suppliers to steel. By 1965, GE had 25 per cent of the world market for process control computers in metals. So the state-owned Welsh steel firm Richard Thomas and Baldwins turned to America for the first complete computer control of their new mill at Spencer Steel Works, Llanwern, near Newport in South Wales, itself a technical breakthrough in mechanical engineering terms.

The designer of the GE412 computer chosen for the task was Arnold Spielberg, who has since become more famous for coaching his son Steven in the art of making home movies. He was a workaholic computer designer, recruited from RCA to head the Process Control Engineering section of GE. He then moved on to IBM before GE sold its computer business.

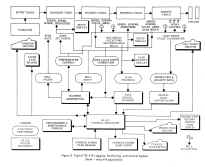

Llanwern was the first successful use of a computer for complete mill control worldwide. In that respect it was the first factory with direct digital control of the whole process from entry to exit. The main functions of the process control computer were initial set-up of the mill, active operation and adjustment during rolling, sequence control of slabs and coils through the mill and logging of production. The computer was also meant to optimise mill performance, but here it was less successful

Commissioning took place in stages. The computer started running in February 1963. The automatic crop shear started in July 1963 and gauge control in October 1963. But it took another year before slab tracking, logging and all the mill set-ups and temperature controls were fully operational by October 1964.

Computer hardware proved surprisingly reliable. During the first 18 months of operation the computer was available for more than 99.9 per cent of operating time. Rather, it was the conventional electro-mechanical features of the mill that caused problems along with shortcomings in the pioneering software.

There are lessons for modern innovation. Only now is the full effect of the digital control revolution being felt, forty years one. An American economic historian, Paul David, points out the transformation of American industry by electric power technology was likewise a long delayed business: “factory electrification did not reach full fruition in its technical development nor have an impact on productivity growth in manufacturing before the early 1920's . . .This was four decades after the first central power station opened for business.”

The slow progress of the “latest technology” highlights a familiar point: innovators face an uncertain and costly learning process. The spread of a new technology is delayed until the leading adopters have overcome teething troubles. Successful innovation requires a process of learning how to use new technology and major reorganisation of manufacturing practices to capture its potential. So, tomorrow's break-through technologies have probably been around for a long time already.

Jonathan Aylen is at PREST - Policy Research in Engineering, Science and Technology, a research centre in Manchester Business School at the University of Manchester.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Contact Jonathan Aylen, PREST, University of Manchester e-mail j.aylen@manchester.ac.uk, mobile 07966-377484; current phone 0161-200 5704 (work), 0161-790 4172 (home); future phone 0161-275 5931

The full 10,000 word research paper is forthcoming in Ironmaking and Steelmaking, December 2004 issue (volume 31, pp. 465-478). Please click here to view the article

|

|

"Phoenix, Arizona Home Of General Electric Process Computers" ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- INTERESTING ITEMS SIGHTED INCLUDED... o License Plate o Template o Tie-Tack

|