History

of ESSCO

By

Jerome

S. Tessler

Founder of ESSCO - C- 2013 - SMECC

FOREWORD

After

my discharge from the USAF in September 1956, (I left three

months early to attend Penn State University) and unfortunately,

when I arrived to register, I was told that all the classes I

needed were full and I would have to wait until the next

semester. I was afraid that the service would recall me and I would

have to complete the three months.

So, I found a two year technical school (Philadelphia

Wireless Technical Institute) that specialized in radio &

broadcast engineering. I wound up with a First Class Radiotelephone license and a

General Class amateur license (K3BHK) plus a good understanding

of RADAR & aircraft communications.

I missed an opportunity to work for WCAU-TV, but the

chief engineer (who was an alumnus) had a heart attack and died

prior to getting all the paperwork done.

So, I took the alternative route and took a job with RCA

in Camden, NJ.

I

started there in September of 1958 and loved every minute.

I worked on projects that took the USAF, (SAC in

particular) into the 20th century with the

installation of the ARC-65.

This was a high power single sideband transceiver which

replaced the earlier AM transceiver units.

When the government projects were through, RCA in their

inimitable fashion laid off people by the thousands and

unfortunately, I was one of them. I was offered a position with a Florida based company

(Electro Mechanical Research) who had subcontracted a NASA

project (Gemini) to RCA. I

went back to work at RCA with a customer hat on.

RCA

had a retail outlet store from which you could buy television

sets, washing machines, refrigerators, phonograph records, et

al. Included was

manufacturing excess and test equipment.

I noticed five high powered UHF transmitting tubes and

bought them for $5 each. I

contacted a company in NYC (Barry Radio) that specialized in

transmitting tubes and they bought them instantly.

I packed them carefully (I thought) and they arrived in a

million pieces, and my only salvation was that I insured them

with the common carrier. The

insurance settlement was enough to give me the financial muscle

to start my own company.

In

the late fifties and early sixties, the amateur radio operators

and some electronic experimenters were anxious to acquire the

glut of military surplus equipment that was available.

I spent many weekends at “radio row” in NYC as well

as the equivalent on Arch Street in Philadelphia buying all

sorts of communications equipment and components.

It wasn’t very long that I had a basement full of

“goodies.” My

wife on the other hand, thought it was all junk and couldn’t

understand the rational. So,

with an order to “get rid of the junk” I started to look for

an inexpensive store front in the City of Camden.

I found a dilapidated store at 324 Arch Street for a

reasonable price, and rented it.

I called the new business “Electronic Surplus Sales”.

The information below may not be in chronological order and the

dates may not be exact.

THE

BEGINNING AND KEY PLAYERS:

The

building was in bad shape and required a large amount of

renovations to make it habitable. A fellow employee at RCA (who was still there) and an ardent

ham, asked me if he could be part of the company.

His name was Jay B. Shaw (K2BZK) who was an electronics

wizard as well as an outstanding carpenter, plumber and general

handy man. Between

the two of us, we made the place look good and I moved all the

“stuff” from my basement to the store.

The building had two floors, the first floor was used for

surplus sales and the second floor we made into a shop and

laboratory. This

was to be used to get some of the surplus equipment in working

order.

Our

store was open in the evening hours and on Saturdays.

At first, business was brisk.

Our customers were RCA people, ham radio operators and

experimenters. The

biggest complaint we had was that the inventory was meager and

not too appealing. I

found a company called Bysel who bought and sold (as their name

implied) all sorts of military hardware.

They had electronics, components and even machine shop

equipment. We

bought a great deal of equipment from them and we quickly

discovered that we also could bid on government surplus.

We were successful about 10% of the time and since Jay

was a pilot, we flew to various government institutions to look

at the stuff we were bidding on.

In one case, we bought a lot of teleprinters from a Naval

Air station in southern Virginia, and sold them in a few days.

It struck me as this was a new market for us.

As

the Japanese manufacturers began to make Amateur Radio

equipment, the market for surplus items began to dry up, but the

teleprinter market was selling.

The RTTY enthusiasts had to build their own “terminal

units” and at the time, all were vacuum tube types.

Many hams had no facilities to do sheet metal work (holes

for tube sockets and bending for the chassis).

I had a Teletype Model 15 since 1958 and I built the tube

type terminal unit. I got the teleprinter from Phil Catona, W2JAV (now deceased)

who was a pioneer in RTTY.

His circuit was published in QST for all hams, but it was

tubes. In most cases the tubes had to be matched for gain and it

took a lot of tubes to do this.

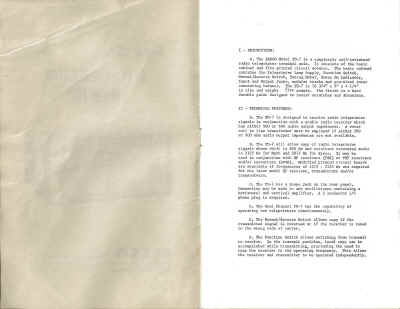

So,

I mentioned to Jay that it would be a good time to build a solid

state version of Phil’s terminal unit.

Phil had no objection other than he wanted some

recognition for his earlier work.

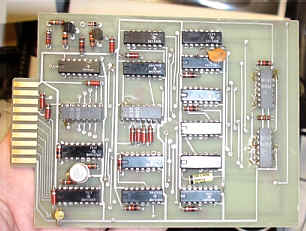

In a few weeks Jay had a working solid state demodulator.

The size was approximately 3 x 5 inches.

It required 5VDC @ low current, and the results were

outstanding. There

were a few technical difficulties, one being that most

teleprinters (of the Teletype ilk) had a polar relay. It was

large, about two inches in diameter and 4 inches tall.

The relay itself was special, it was similar to a single

pole double throw relay and the difference was that the armature

of the relay was centered between the two contacts.

It was a delicate balance and only the foolhardy would

attempt to make any adjustments to the relay.

A slight mis-adjustment resulted in poor teleprinter

performance. A positive signal (mark) caused the relay to close

in one direction and a negative signal (space) caused the relay

to close in the opposite direction.

The output of the polar relay was sent to the selector

magnet which then chose the key to be printed based on the

Baudot code that was generated.

The

demodulator amplified the input mark and space tones, then

limited them so that they would almost be impervious to level

changes. The mark

and space signals were separated by two tuned circuits.

Both signals would be rectified and then amplified again

and then their outputs would be fed to the polar relay.

This provided the necessary signal to make the telprinter

function. We also

provided an output for a center scale meter so that proper

tuning could

be made. The Baudot code consisted of 7 bits, one start bit, 5 data

bits and one

stop

bit.

Some

teleprinters did not have a polar relay or their owners did not

want to use it, so this presented a problem which plagued us for

a long time. Our

goal was to eliminate the relay and just drive the selector

magnet directly. There

were many transistors that could provide the necessary current

to the selector magnet, but none that we could find that could

withstand the “inductive kick” for the selector magnet when

the field collapsed. The

reverse voltage was in the vicinity of 400VDC

which caused the transistor to fail.

Snubbing the reverse kick saved the transistor but caused

the teleprinter to lose “range.”

Range was a mechanical measurement to determine how well

the machine was adjusted. There

was a rangefinder arm on the teleprinter which went from 0 to

120. If a constant

signal of RY’s was fed to the machine, the rangefinder was

moved down until the teleprinter began to make mistakes. The number on the rangefinder was so noted and then the arm

was moved upward until the machine began to malfunction. That number was also noted.

If the low number was 20 and the upper number was 100,

the range of the machine was 80.

The rangefinder would then be set to 60. This was the

ideal range. The

trick was to get the output transistors not to fail and that the

range of the machine would not suffer.

It took a few months, but we finally got it and then we

had the first solid state demodulator and one which did not

depend on a polar relay.

We

let the surplus business slide and spent all out time trying to

develop a marketing strategy. We decided to use the “Heathkit” approach and sell the

demod as a kit. Jay

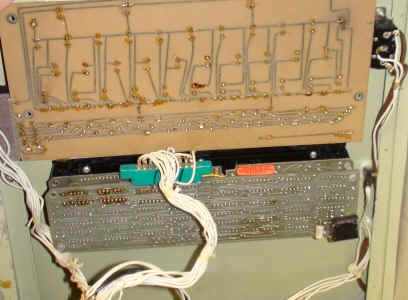

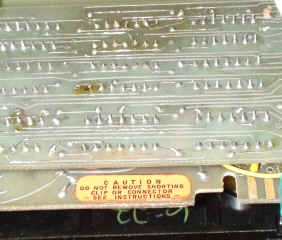

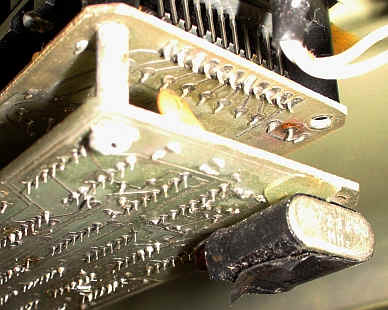

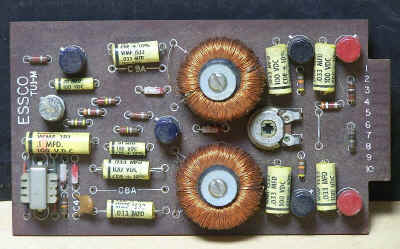

designed the PC board and 100 boards were ordered.

We also bought the other component parts, but the fly in

the ointment was the tuned circuits.

We needed a high “Q” tuned circuit and the surplus

torroids from the phone company were the ideal things.

They were two 44mh coils and if wired in series became

88mh. A .033

polystyrene cap with an 88mh coil resonated at 2975Hz (the space

frequency) and an .068 cap with that coil resonated at 2125Hz.

The caps were plus and minus at least 20% so it took many

hundreds of caps and fiddling with the turns on the coils to

achieve the proper frequencies.

The torroids were surplus and were used by the phone

companies to compensate for various effects on their lines.

They were packed 5 to a tube and invariably encapsulated

in pitch. Getting

the pitch off was a problem, but was solved.

HP was just making counters available, but they were in

the thousands of dollars and a small company could not afford

one. We found a tuning fork whose frequency was 400Hz and it was

modified to produce a tone at 425Hz.

If that tone was multiplied by 5 and 7 times, it resulted

in tones of 2125 and 2975Hz which of course were the mark and

space frequencies. We

did have an early Tektronix scope and by using Lissajous

patterns we could determine the frequency down to a very small

factor.

The

interest was very promising and Jay and I needed help in the

shop to kit the demods and to tune the frequency sensitive

items. Now, the

third player entered the employ of Essco.

There was a 17 year old boy (who was also a ham –

WA2MES at the time)

working at McDonalds flipping burgers.

Jay knew the kid and we hired him part time.

He had won a scholarship with the Philco Technical

Institute and was available to work part time.

He was very ambitious, very technically minded and he

became the right hand man for Jay. There were times when he had better ideas than each of us and

he was the best thing to happen to us in a while.

His name was Joseph Harmon Everhart, but liked “Harm”

and he was a total asset to the company.

He finished his scholarship with Philco and since I could

not afford to hire him full time, he went to work at RCA as a

technician. He met

his wife there, and she promptly got him to quit RCA and go to

Drexel to get a BSEE, which he did.

He also continued to work for us part time and his

engineering discipline helped us considerably.

Harm eventually left us and went to work for a few

communications companies and he eventually returned to RCA as a

Class A engineer and he became a respected member of their

engineering community. He

is now retired and I haven’t talked to him in a few years.

The

kit, although a good seller, was not what the hams wanted.

They wanted an all in one terminal unit that contained

what was necessary to make their RTTY station work.

We stopped building kits, and started building an AFSK

unit a band pass filter and power supply.

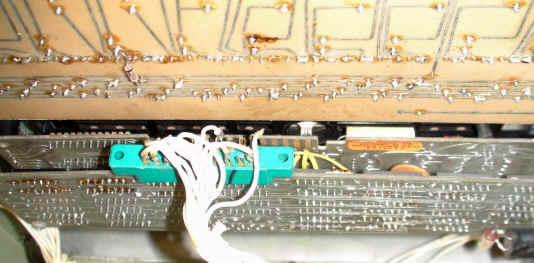

We adopted a modular design in that a backplane was

developed so all the cards could be plugged in with no internal

wiring. Bud had a

cabinet we could use and it looked nice and we started selling a

once piece unit to the ham radio community.

We advertised in QST, CQ, 73

and Ham Radio magazines

with excellent results. During

this time, Harm left and we hired James A. Steel Jr., an

electrical engineering student at Drexel.

He was also part time and worked after school and on

Saturdays. He was

quite bright and was an asset.

In 1964 or thereabouts, Jay decided to leave. Now there were two of us, Jim did any assembly or design work

and I bought the parts, paid the bills and generally ran the

business.

I

received a phone call one afternoon from I. Lee Brody who

identified himself as partially

hearing individual who wanted to know if we could build a modem

for use with the deaf. Lee

and Apcom had a falling out over the price of Apcom’s modem

and Lee felt there would be a nice market if we could make what

he considered an affordable modem for the deaf.

Lee was an agent for TDI and he represented all of NJ and

eastern NY. The ham

radio orders, although still good, had begun to fade as we

saturated the limited amount of ARO’s that needed terminal

units. The deaf

market sounded great and was a new opportunity for us.

Lee sent me a Apcom modem, and it was a decent unit with

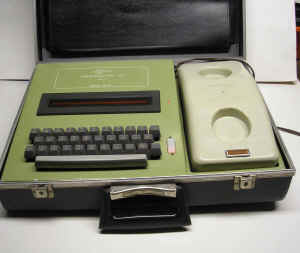

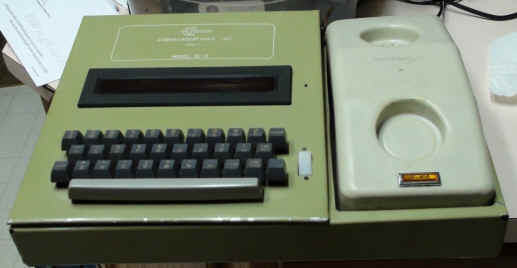

the exception of the box holding the handset.

It looked like a cheese box and that part of the modem

was not very professional. We determined that the mark frequency was 1400 Hz and the

space was 1800 Hz. This

was a narrower shift than the ham equipment.

Jim modified one of our units and we had a deaf modem in

the making.

The

major difference between the deaf modem and the ham modem was

that the ham modem received its input signal from the radio,

whereas the deaf modem derived its signal from the telephone

handset. The

“cheesebox” approach was not plausible, so I decided that an

injection mold be made to house the handset.

The handset had to fit precisely right and fortunately

for us, I had a good mechanical engineer friend who designed the

mold. It took just

about everything I had in the bank to pay for the mold, but it

came out nice and looked well.

There were bosses on the mold that allowed for a plate

which contained the electronics and holes for connectors.

The phone companies would not allow direct connection to

their phone lines (Part 68 was many years away) so the transmit

and receive signals had to be made acoustically. We had made provisions in the mold to allow a coil to be

placed where the handset would be and the received signal was

induced and was sent to the input of the modem.

The transmitting side was just an ordinary microphone

glued to the inside of the case.

Both

proved to be a very difficult problems.

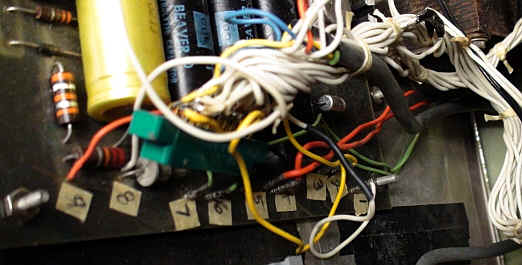

I wanted the power supply to be built into the modem.

This would make the modem completely self contained

without any external cases. Apcom had a built in supply but an external handset holder.

Having the power supply and its attendant transformer

created a large magnetic field which desensitized the

incoming signal. Instead

of having a useable -45dbm signal, it was reduced to -20dbm.

This was unacceptable.

Low signal levels on the phone line would result in

extremely poor performance.

We tried all sorts of shielding on the transformer but

the needed sensitivity was never achieved.

There was an AC/DC solution which I offered, but Jim was

afraid of a shock hazard so we had to use a separate power

supply, which solved the sensitivity problem.

The microphone had to be sensitive, but it proved to be

receptive to noise in the room, babies crying and dogs barking.

To make the microphone less sensitive resulted in a

transmitted signal that was much weaker than what was

acceptable. Apcom

had the same problem and lived with it.

We experimented with different type of mikes and finally

settled on one that was acceptable.

We

went into production the latter part of 1964 and I hired a few

assemblers to put the modems together.

We advertised in the TDI Journal and Lee Brody sold

hundreds of modems to people in or around NYC.

Then, the mold broke, and as much as the machinist tried

to weld it, it was not good.

I didn’t want to invest in another injection mold

primarily because of the time factor and cost.

The injection mold piece prices were in the pennies in

large quantities and that was my original plan.

Now that it was ruined, I had to go to a different type

of molding. This

was called vacuum molding and the piece price now was in the 5

or 6 dollar range per piece.

The quality was not as good, but it was acceptable and we

had orders to fill.

Electronic

Surplus Sales was a sole proprietor, but surplus was the wrong

message to send to the deaf.

So the company became incorporated and took the name

Essco Communications, Inc. The company moved to 2402 Federal

Street in Camden and then two years later to 150 Marlon Pike in

Camden. During this

time period, I was approached by the “boy wizard of Wall

Street”, namely Paul J. Goldin (now deceased).

He and a group of lawyers (who specialized in public

offerings) had a holding company called Management Dynamics.

He offered me a large number of shares in his company for

all of my company. He

further stated that he and his group would take all companies

that he owned public. The

thought of becoming wealthy overnight interested me, and I

agreed to sell. It

was a good decision at the time, but ultimately a bad one.

Paul and his band of merry men, wrote a prospectus for

Essco and I spent many days in NYC visiting many Wall Street

types who would underwrite the public offering. I left Jim in charge in my absence and he did an admirable

job. I spent months with accountants and we were ready to go

public when the market tanked and Paul decided to wait for a

more advantageous time. This

was the downfall of Management Dynamics. Management

Dynamics became strapped for cash and had each of his 5

companies borrow large sums of money from

a capital company in NYC.

I had to sign for the financial proceeds that I received

and had to put my home up as collateral. Most of it the money

received was appropriated by the parent company and I was left

with the monthly payments.

In

the meanwhile, our sales to the deaf were OK, and I managed to

pay the salaries and bills with the proceeds of the sales.

I got the boy wonder to accept an offer for the majority

of stock by a close friend, a medical doctor in Trenton, NJ. Arnold

Ritter (now deceased) was the majority stock holder but he could

not exercise any of his rights until the loan to the sharks in

NYC was paid. Arnold helped me pay the monthly payments when I needed him.

After two years he finally was Essco’s owner.

With the doc as our owner, he wanted us to fiddle with

medical devices and we came up with a few.

Particularly noteworthy was a gadget that measured your

heart rate by inserting a finger into a black box and counting

the number of LED flashes.

I went on “What’s My Line” and even with a

nationwide audience, I managed to sell two of them. After

that, he stayed in the background and let me run the company.

In

order to be successful, our product was based on the

availability of TTY machines.

They were few and far between and not having a

teleprinter to go with our modem, normally resulted in a loss of

a sale. The teleprinter was bulky, noisy (not that it mattered),

dripped oil and was not a good looking piece of furniture. I was in McDonalds one day and noticed they had a moving

display at the cash register that contained the sales and price

information. A

little digging and I found out that the displays were made by

Burroughs and they were available.

They had two versions a large display of 12 characters

and a smaller display of 24.

They were expensive (over $300 a piece) and required a

high voltage power supply (300VDC or so).

I bought two of them for engineering experiments.

Joseph Elmaleh walked through the door and had an

interest in teleprinters. I

mentioned that I was investigating a replacement for the

teleprinter and he indicated that he was an electrical engineer

and a lawyer. He

made me a proposition that he would design and build the deaf

version and that he would make an ASCII version as well in which

he would own the rights. I

would be required to pay for the parts. It took Joe about a

month to have two working models. The deaf prototype was shown to various deaf institutions

including Gallaudet College in Washington DC and to Dr. Phil

Bellefleur, headmaster of the PA School for the Deaf in

Philadelphia. Various

agents of TDI also saw the “Scan-A-Type” but their objection

was price. Dr. Phil

was to attend a meeting of deaf educators in San Francisco, and

asked If he could demonstrate to his peers.

I let him have the device and he said it was highly

accepted. It was

accepted so well that it spawned a few competitors, particularly

one who eventually built a wonderful small one line display that

was very reasonable.

In

the meantime, Lee Brody was on a one name basis with the chief

engineer of AT&T in NYC.

We were invited to attend a meeting to determine

AT&T’s interest in the product.

There was a conference room with many engineers and

company lawyers. Only

Joe Elmaleh, Lee Brody and myself represented Essco. We demonstrated the product and you could tell they were duly

impressed. They

made us three offers, none of which were acceptable and we left.

I knew the product would not sell and it was scrapped.

I got a call from a Wall street type who wanted to meet

with me to discuss the Scanatype. He was willing to finance the project. He asked me how many orders I had and when I replied zero, he

slammed his fist on his desk and shouted “show me the orders

and I will show you the money.”

I never forgot that good piece of advice.

I

was in my office reading an electronics magazine when an article

struck me. Some

country in Scandinavia was concerned with their senior citizens

and put sensors under their carpets.

If the sensors detected movement, the senior was OK.

It was a trial program, but it brought to light that the

same problem existed here.

A senior citizen could have a heart attack or some other

problem and could lie on the floor forever.

I thought if we could devise a telephone dialer that

would call the police or a family member to help the stricken

individual. The

impetus for the dialer would be a transmitter (turned out to be

a garage door opener) which when the send button was pressed, it

would activate the dialer.

Coincidentally, Harm showed up and needed a job, so I

hired him full time and this was his project.

In a few weeks we had a working model and called it

“Tele-Aid.” I

got a huge amount of interest from investors, (including a

partner in Price Waterhouse who offered me $100K), but we were

stymied by the phone company who would not allow access to the

switched public telephone network. Of course, if you wanted to pay $20 a month, magically, they

would provide a box that contained two diodes.

The investment money dried up and that project died.

Today, it is being advertised on TV with the same

concept.

A

few weeks later, Jim walked into my office and demanded that his

salary be doubled. If

I didn’t give him what he wanted, he was going to quit.

As it turns out, he did exactly that, and he and Lee

Brody started a competing company which almost instantly caused

our demise. To add

insult to injury, the doctor who was the majority stock holder

got into financial trouble and he sold his shares to two

accountants. These

accountants only goal in life was to take company funds and use

them to buy new cars and pay off their debts.

I was down, but not out.

Being

on RTTY as a ham (my call letters were changed to W2GIA when I

moved to New Jersey) gave me pause for thought.

The concept of a deaf radio station crossed my mind and I

began to pursue it. Putting

audio signals on a radio station is routinely done, but putting

audio tones on a FM sub-carrier was not.

I went to the FCC in Washington and had a long talk with

the engineers with regard to doing just that.

I told them that nothing in their rules prohibited the

concept, and they replied, no where does it say it was allowed.

Since I could not use commercial or not for profit FM

radio stations, I petitioned the FCC for just one VHF frequency.

Although, very sympathetic, they denied my request.

It was very frustrating to have a viable idea that was

technically possible but was stopped in its tracks by vague

rules and regulations. A

few months later, a station in Florida petitioned the FCC to use

audio signals on their sub-carrier and it was tentatively

approved, and eventually approved.

One obstacle was gone, but a larger one loomed.

I had to find an FM station that was willing to let me

use their sub-carrier.

I

called every single FM station in the area and found that most

of the chief engineers did not have a clue as to what a

sub-carrier was or what effect it would have with their existing

main channel. Most

of them felt using the sub-carrier would diminish their power

output (absolutely not true) and their advertisers would suffer

since their signal would be less.

I did find one or two stations that would allow the use

of their sub-carriers, but they wanted huge sums of money, which

was out of the question. I

finally stumbled on Temple University and found them very

amiable to what I wanted. Dr.

Harwood liked the idea since all the needed equipment would be

paid for by Essco, and further he had to right to use the

sub-carrier generator for his own school’s needs anytime the

deaf were not on the air. Now

I had the FCC permission and a FM radio station (WRTI-FM), all I

needed was the acceptance of the deaf community to the idea and

a way to raise runds to pay for all of this.

At this time I hired Randy Acorcey, an excellent engineer

who understood all the vagaries of this project.

The funding was eventually provided by the Neville

Foundation whose charter was to provide for the deaf and blind.

They always provided for the blind, particularly with the

talking book program on WHYY-FM.

The foundation paid for the radio time and the

sub-carrier radios the blind needed.

It took a rather lengthy proposal (which I wrote in part)

to get the Neville group to fork over the money which amounted

to close to a half a million dollars.

The deal was that the deaf would use the money to buy

TTYs for those deaf without one, all the modems required, all

the radio receivers required and pay for the equipment at

Temple. Additionally,

they would fund the money necessary to build a studio at the

school for the deaf. They

did just that, but bought most of the modems from Apcom.

That’s the thanks Essco got.

We got everything built and the world’s first radio

station went on the air a few months later.

It was a huge success, but unfortunately, the funding ran

out in three years and the project was cancelled.

Temple as far as I know still has the equipment provided

to them free of charge.

News

of the deaf radio station reached those powers to be in the NOAA.

They called and asked if it were possible to put a

sub-carrier on their narrow

band VHF radio signal. We

looked into it and Randy managed to do the impossible.

I asked for, and got permission from the top guy at NOAA

to modify their radio transmitter.

I got the approval and Randy and I put the “fix” in.

For two solid weeks NOAA pumped out thousands of lines of

RY’s without an error and without interfering with their main

channel. Their

chief engineer called and demanded to know what fool in NOAA

gave me permission to modify a government transmitter.

The silence was deafening when I read him the letter of

authority signed by their head man.

Nothing really came of this, although they proposed

having hundred of radio receivers for use with sub-carrier

transmissions on their VHF radio stations.

The

accountants who owned the majority of shares in Essco had bled

the company blind to the point where the only alternative for

Essco was bankrfuptcy.

Essco

did a fair amount of work for RCA’s test equipment division in

Harrison, NJ and one of our competitors was Diversified

Electronics in Philadelphia.

The company was owned by Bernie Shuman who was a contract

manufacturer and had no capability as an engineering company.

Although Bernie was a graduate EE, his time for design

had come and gone. Randy

Acorcey was a bright engineer loaded with ideas.

So, I got an offer from Bernie to sell Essco.

Even though there was little money left, the accountants

played hard ball and wanted big bucks for Essco.

I pointed out to them, it was better to get something

than to get nothing and then go thru bankruptcy proceedings.

Bernie and the accountants reached an tentative

agreement, but Bernie was a few thousand short.

I came up with the cash necessary out of my own pocket

and the deal went through. Diversified Electronics became

Essco’s new owner. The

company moved from Camden, NJ to 4969 Wakefield Street in

Philadelphia. Randy

and I were the only two Bernie kept and the others were let go.

Once

ensconced in Philadelphia, Randy had the responsibility to build

the studio at the Pa School for the Deaf. It was a big undertaking, but Randy was quite good and the

station looked beautiful. Dr.

Phil assigned one of the deaf teachers to manage the radio

station. His name

was Joe Spishock and he did a wonderful job.

The local news, weather and sports were compiled by his

people and put on punched tape so that the data could be sent at

the high rate of speed (60WPM). We worked out a deal with UPI who provided us with a feed for

national and world wide news.

They did this at no charge which I thought was very

gracious of them. We

were 15 miles or so from the Temple University studio so in

order to get the signal from PSD we leased a DC pair from the

phone company so we could send our data to Temple.

Turned out we needed a conditioned line, but all was well

in the end.

Proposal

for PA School for the Deaf Subcarrier...

Word

of the radio station quickly spread and I started getting phone

calls from schools for the deaf and TTY communications from the

deaf in general. Pittsburgh

PA showed a lot of interest and I was asked to submit a proposal

to either the Mellon or Carnegie foundations.

I did and was surprised to hear that they would fund a

similar project in Pittsburgh.

This was conditioned that I find a radio station that

would be willing. I figured I might as well start at the top and called KDKA-TV/FM.

The general manager was quite receptive to the idea and I

went to Pittsburgh to finalize the deal with KDKA and the

foundation. At the

meeting there was a deaf man who insisted he had to be included.

We were ready to sign all the papers when the deaf guy

stated that there had to be an “ad hoc” (the deaf loved the

Latin wording) committee and a meeting was set up between the

deaf folks and the general manager of KDKA and me.

There was a heated discussion (remember that the deaf

were to get everything free) and the proposal was voted down.

To this day I am totally disappointed.

Then,

there was a new wrinkle, a deaf man in the department of Health

& Welfare (I wish I could remember his name) was looking for

a way to allow the deaf to see television and have the spoken

word displayed on the TV screen.

This was the beginning of putting closed caption signals

on line 21 of the vertical retrace scan.

I wanted to use the FM sub-carrier technique, but I was

overruled and line

21 became a reality.

Meanwhile,

back at Essco, Randy was involved with many small projects, i.e.

door bell ringers, wireless devices

et al. We

got a call one day from the Headmaster of the Connecticut School

for the deaf who described a tragic event that took place in his

school that had some fatalities.

There was a fire in the school

at it seems that they had no smoke alarms or fire

detectors for the kids, and even though the standard alarms

worked, the kids could not hear it.

So, we got involved with smoke and fire alarms for the

deaf. The specs

called for non-battery units with wireless access to strobe

lights. We put

together what we called “Smokatron.” and sold quite a few.

Randy

in his own fashion decided that hearing people had telephone

answering machines, but the deaf did not.

He designed an answering machine for the deaf in

conjunction with TTYs. We

even personalized the message that the caller would read. That was quite a feat at the time. We called it “Directcom.” It was a marginal seller, but the sales paid for the cost of R

& D.

The

Community College of Philadelphia had a fair quantity of deaf

students. There was

a hearing fellow named Aram Terzian who was their mentor and

instructor. He gave

us a contract to build a classroom loaded with TTYs and

switching equipment to allow the teacher to communicate with any

or all students using the TTY’s.

It was a lengthy project but it turned out wonderfully

for all concerned. Aram

Terzian was promoted to head of the community college.

Finally

FCC’s part 68 was law and everyone was free to use the phone

companies telephone network without fear of reprisal.

There was one caveat, in that anyone wanting to use their

network would need an approved FCC interface.

The specs were provided by the phone company.

Randy built and submitted the interface to a company that

the FCC had authorized to do their technical work.

It took four months, but we had an approval to connect

any of the deaf communication products to the telephone line.

The irony is that the phone company who proposed the

specs to the FCC failed to meet their own specifications and

they had to be “grandfathered.”

We licensed the rights to other companies working with

the deaf. No one else was willing to spend the time and money to do

this. Most also

lacked the technical expertise and they really didn’t need it

since their product was designed and manufactured in the far

east.

By

this time it was mid 1979 and we got a panic phone call from the

top guy at Western Electric in Cincinnati, OH.

He was in the panic mode and blurted out to me that he

was directed by Charlie Brown (then CEO of AT&T) to build

terminals so that the deaf could communicate with the phone

companies all over the country and Canada.

They (Western Electric) had no idea how to build such

equipment and somehow they found us.

It was required almost instantly and his question was

“how soon.” It

was not “how much.” Bernie

got involved since this was a high profile contract

and he

negotiated the deal. It

was pretty close to a half a million bucks to build 4 units. This

was Randy’s project. I

went to Cincinnati to discuss specifications and the project was

underway.

In

the early part of 1980 Bernie and I had a difference of opinion

and it got so heated that I looked for a job and found that RCA

was looking for an Administrator.

The fellow who needed the new employee was an old friend

from my days at RCA and I was quickly hired.

I announced to Bernie that I was leaving and he did not

take the news well. But

needless to say, I did leave in March of 1980 and I never did

see the outcome of the AT&T ESV-1 terminal project.

Even

though I no longer was part of Essco, Joe Spishock and I

collaborated on a new project for the deaf.

The funding for the deaf radio station was about to

expire and we had to find an alternative. Seems, that the Corporation for Public Broadcasting had a

communications satellite. They

were willing to let us use one 5KHz audio channel for deaf

radio. It got

complicated technically and economically and it never came to

fruition despite a lot of effort.

In

conclusion, I felt Essco provided many projects for the deaf in

general and received very little in recognition.

I am sure that many of the projects we did are not in

this narrative. We

were years ahead with most of our projects and were thwarted at

almost every turn with government regulations and red tape.

But we gave it a good try and I am not sorry in the

least.

Jerome

S. Tessler

- 2013

Joseph S. Elmaleh, 82, of Elkins Park, a lawyer, computer engineer, and colonel in the Army Reserve, died of cancer Sunday, June 20, at Einstein at Elkins Park.

Joseph S. Elmaleh, 82, of Elkins Park, a lawyer, computer engineer, and colonel in the Army Reserve, died of cancer Sunday, June 20, at Einstein at Elkins Park.